Research/Academic Showcase

Building New Hope

It’s a hot day in El Chorrillo Nuevo and the streets are jumping.

Shoppers stroll through clothing stores. Kids shoot hoops on basketball courts. Tired pedestrians duck the sun in cafes, where they sip espresso and rattle through newspapers. As the main corridor linking two of Panama City’s hottest tourist spots, the neighborhood is a vibrant sector of the city providing hot retail and restaurant offerings.

Consider this a snapshot of what could be.

Here is El Chorillo Nuevo as it exists today: Ravished by crime, strapped

with unemployment, terrorized by gangs – “the whole nine yards,” notes

Michael Mussotter, an associate professor in the College of Architecture.

Here is El Chorillo Nuevo as it exists today: Ravished by crime, strapped

with unemployment, terrorized by gangs – “the whole nine yards,” notes

Michael Mussotter, an associate professor in the College of Architecture.

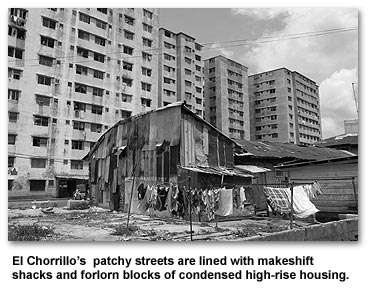

Home to 23,000 people, El Chorrillo Nuevo once served as the headquarters of former Panamanian military leader General Manuel Noriega. The neighborhood is tucked between retail and cultural hubs that attract the bulk of city tourists. Yet with its scant retail offerings and patchy streets lined with either makeshift shacks or blocks of condensed high-rise housing, the area itself gets little traffic.

This landscape, Mussotter says, invites crime and gang activity. And while there have been spotty efforts to add new housing in recent decades, Mussotter says an all-encompassing renewal strategy has never been developed for the area.

This could change as a result of an urban renewal project developed by Texas Tech architecture students who travelled to Panama last summer to complete an elective interdisciplinary program for graduate students studying land use, planning, management and design. The program, held in conjunction with Penn State University and the University of Panama in Panama City, teaches students to tackle the daunting challenge of giving the area a physical and social facelift.

“Reviving neighborhoods – especially those that have sunk this

low – takes more than just architecture and design,” Mussotter

says. “It requires a holistic approach.”

“Reviving neighborhoods – especially those that have sunk this

low – takes more than just architecture and design,” Mussotter

says. “It requires a holistic approach.”

Texas Tech students eventually compiled a large enough body of work that they submitted an urban renewal proposal to the Ministrio de Vivienda República de Panamá (Panama's ministry of housing). Additionally, Mussotter has pitched the plan to other local government officials and residents during three presentations given in the country.

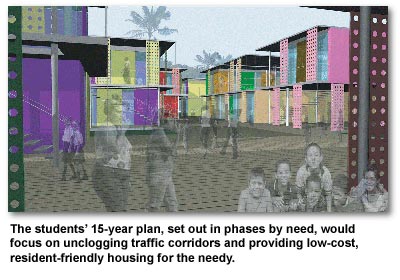

Their 15-year plan, set out in phases by need, would focus on unclogging traffic corridors and providing new, resident-friendly housing while cleaning up the area’s fragmented block structures. Foot traffic would be bolstered in residential areas through mixed-use buildings that stack housing on top of retail centers. The city’s shoreline would be used as a major thoroughfare to connect hot tourist locations.

The housing would be mostly low-technology to help hold maintenance expenses to a minimum. The plan would also seek community buy-in by allowing residents to be involved in the creation and decoration of the buildings. The students based building designs on Panama’s culture, using vibrant and varying colors.

So far, the proposal has met with interest, Mussotter says, and Texas Tech�s efforts have enjoyed lavish coverage from two of the city�s most important papers, El Panam� Am�rica and La Prensa. Mussotter is in contact with ministry officials about long-term collaborations and possibly applying the renewal strategy and housing typologies developed for El Chorrillo to other Panamanian communities in dire need, such as the impoverished City of Colon located at the northern end of the Panama Canal.

Mussotter points out, though, that sustainable renewal plans take time and patience. There must be an overhaul to the social as well as the physical environment.

--Cory Chandler