OCELOT

Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus 1758)

Order Carnivora : Family Felidae

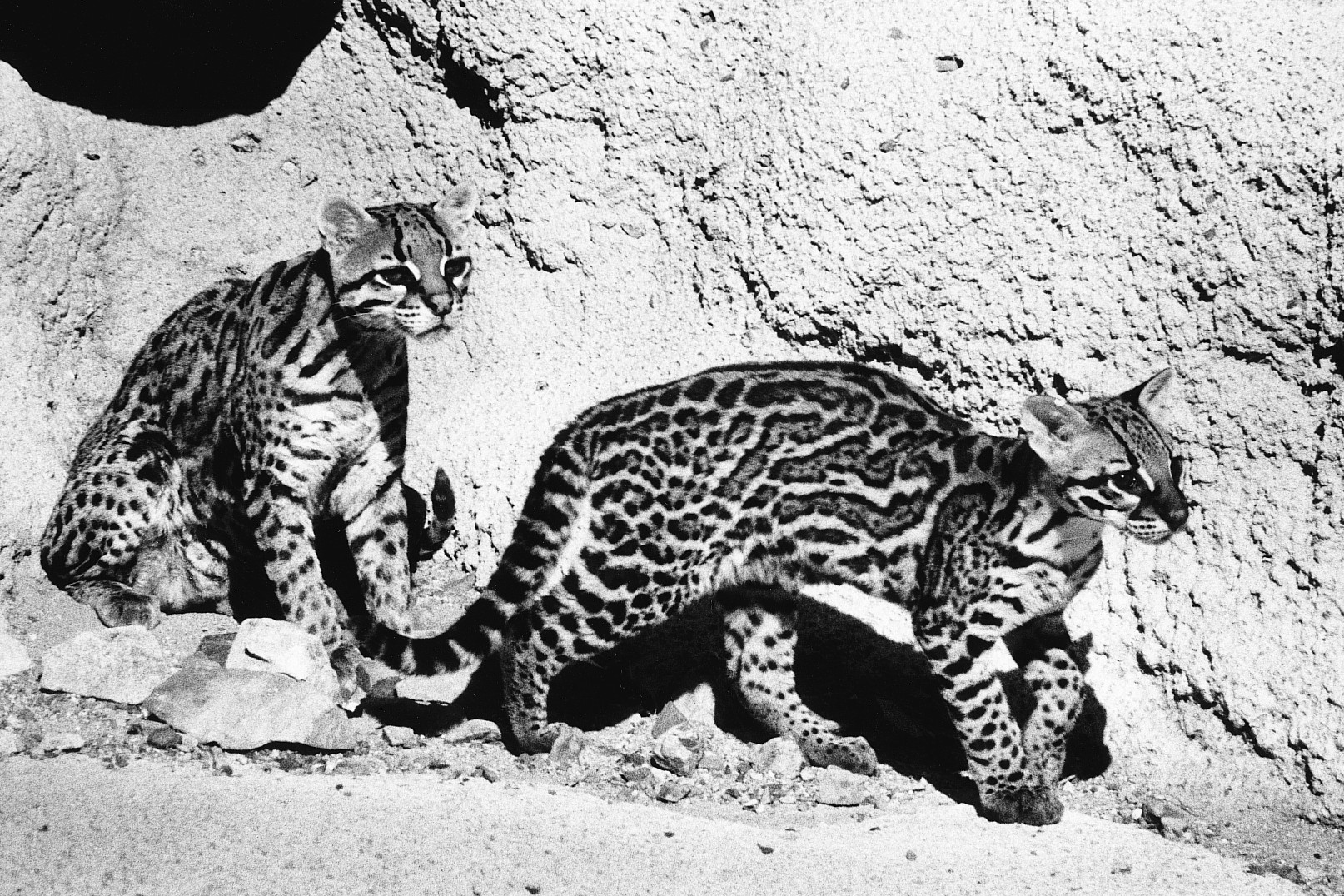

DESCRIPTION. A medium-sized, spotted and blotched cat with a moderately long tail; about the size of a bobcat but spots much larger, tail much longer, and pelage shorter; differs from the jaguar in much smaller size and in presence of parallel black stripes on nape and oblique stripes near shoulder; upperparts grayish or buffy, heavily marked with blackish spots, small rings, blotches, and short bars; underparts white, spotted with black; tail spotted and ringed with black; both sexes colored alike. Dental formula: I 3/3, C 1/1, Pm 3/2, M 1/1 × 2 = 30. Averages for external measurements: of males, total length, 1.1 m; tail, 355 mm; hind foot, 157 mm; of females, 930-285-135 mm. Weight, 10–15 kg.

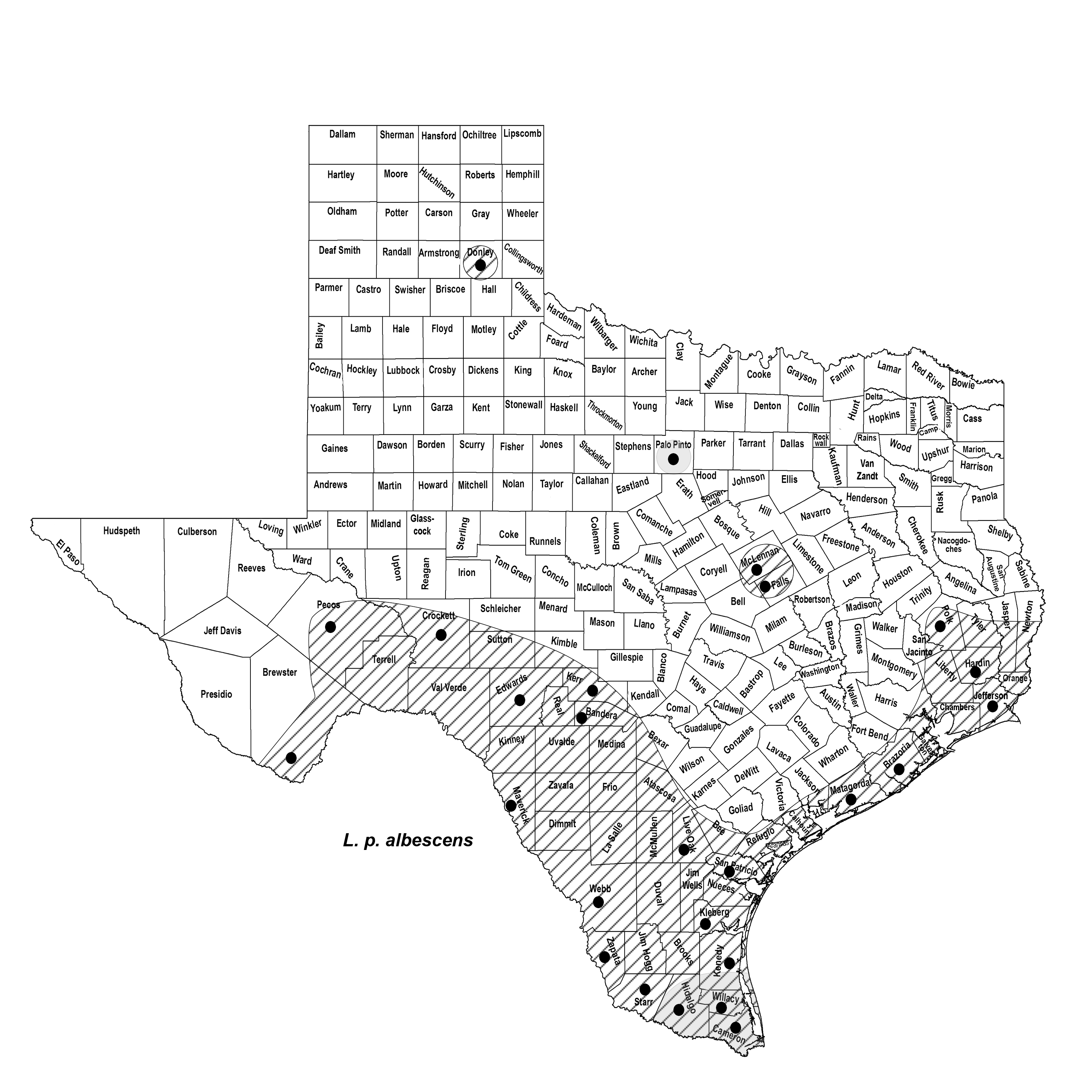

DISTRIBUTION. Once ranged over southern Texas with occasional records from east and central Texas; now restricted to several isolated patches of suitable habitat in four or five counties of the Rio Grande Plains.

SUBSPECIES. Leopardus p. albescens.

HABITS. The ocelot is a Neotropical felid that once inhabited the dense, almost impenetrable chaparral thickets of South Texas, the Gulf Coast, and the Big Thicket of eastern Texas. In Kerr County, where ocelots occurred as late as 1902, rancher Howard Lacey reported that he found them in the roughest, rockiest part of the dense cedar brakes. He was of the opinion that they travel in pairs and that they often use trees to escape dogs.

Ocelots feed on a variety of small mammals and birds, as well as some reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Lacey reported that they are fond of young pigs, kids, and lambs; in the early twentieth century Edward W. Nelson reported that birds, including domestic poultry, were captured on their roosts, and rabbits, woodrats, and mice of many kinds were important items in their diet.

The den is located in the densest part of a thorny thicket. Typically, one to two kittens are born in the spring or fall. Like other young of the cat family, they are covered with a scanty growth of hair, and the eyes are closed at birth. Gestation has been estimated to last 70–80 days, and captive kittens opened their eyes 15–18 days after birth.

POPULATION STATUS. Rare. Predator control and habitat destruction have greatly reduced the range and numbers of the ocelot in Texas. Although still abundant in parts of Mexico, Central America, and South America, within the United States the current ocelot population consists of fewer than 100 individuals generally confined to two isolated populations restricted to small patches of suitable habitat in four or five counties in southern Texas.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the ocelot as a species of least concern, but it is listed as endangered by both the USFWS and TPWD; some subpopulations are considered threatened. Modifications of the landscape during the twentieth century, as a result of mechanical farming and brush eradication in the Rio Grande Valley, have fragmented its range, reduced its numbers, and created barriers to dispersal between South Texas populations and the larger, more continuously distributed populations in northern Mexico. Habitat restoration and corridor construction will be important in enhancing its recovery. Also, vehicular traffic is the primary source of mortality for ocelots in Texas. Conservation efforts and research by Michael Tewes and colleagues (at Texas A&M–Kingsville) over the last 30 years recently have helped stabilize populations. The key to recovery will be the active participation of private landowners in South Texas.

REMARKS. In previous editions, the scientific name for the ocelot was given as Felis pardalis.

Surprisingly, in 2010 a road-killed ocelot was obtained by Fred Stangl (Midwestern State University) in Palo Pinto County, far from the nearest documented populations in South Texas. On 28 March 2010, the road-killed body of the adult, scrotal male ocelot was retrieved by a TPWD game warden from Highway 180, approximately 3 km (2 mi.) east of the town of Palo Pinto. One of four possible scenarios might account for an ocelot in north Texas. First is that the animal simply traversed the 850 km (528 mi.) separating the Palo Pinto locality from known South Texas populations. This seems unlikely for a species with a typical dispersal distance of approximately 10 km (6 mi.). A second possibility is that the animal escaped from a captive setting—these animals are known to be popular with exotic pet fanciers. Third, it is possible that someone killed the ocelot or retrieved the ocelot carcass from one of the South Texas populations and transported it to the Palo Pinto locality and, fearing legal repercussions, disposed of the carcass. Fourth, there is the possibility that the specimen represents a secretive and uncommon species that has a more widespread occurrence across the state than is currently suspected. To resolve this question, there is a need for field biologists and wildlife professionals to be on the lookout for rare species such as the ocelot and to carefully document any reports or sightings.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu