Uncovering Mayan Culture

By: Crystal Price

Little has been known about the Mayan culture, but one Texas Tech researcher is digging into the culture by analyzing tombs and bones. Anna Novotny, assistant professor of physical anthropology and bioarcheology, is using archeology and osteology, the study of the structure and function of the skeleton and bony structures, to discover how the Mayan people lived during the Classic period (AD 500-900).

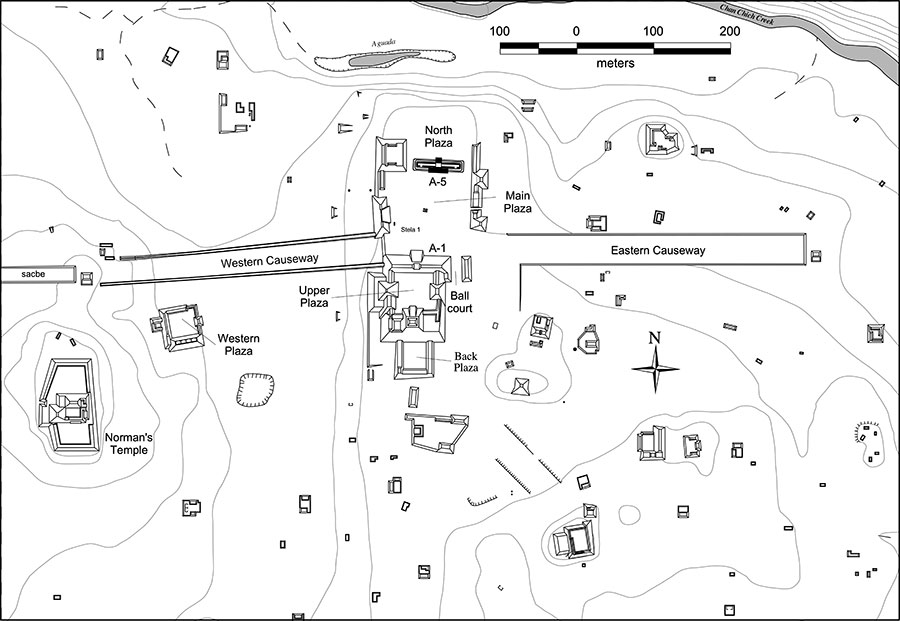

Specifically, Novotny directs the bioarcheology component of the Chan Chich Archaeological Project (CCAP), which is directed by her Texas Tech colleague Brett A. Houk, Ph.D. Houk has worked at Chan Chich for more than a decade, and Novotny joined the project when she came to Texas Tech in 2015.

Chan Chich is an ancient Maya city located in northwestern Belize on the eastern coast of Central America. Novotny chose Belize not only because it is a great place to take field students, but also because of the rich history and diverse populations that settled there including Spanish, Afro-Caribbean, and British along with the indigenous Maya people.

Novotny excavates in and around Chan Chich to learn more about how the Maya lived and died through their skeletal remains. Since 1997, CCAP has excavated 22 burials. The ancient Maya did not bury the dead in cemeteries but rather buried their loved ones in architecture, such as beneath the floors of their homes, in temples, or in benches raised on a platform, overlooking the plaza. "The majority of the time it's difficult to know how many remains you may find. It could be one or five," Novotny says, "It all depends on where you choose to excavate."

The skeletons Novotny finds are usually not well preserved. Several factors influence why the bones are not complete such as the acidic soil in the area, getting crushed by the weight of soil or a capstone, or climate, which is very wet in this region.

The reuse of tomb space also influences what CCAP finds, since multiple bodies may have been entombed in one space. "Before we take out the remains," Novotny said, "we create line drawings to scale of the skeleton and artifacts, and we take lots of photographs to represent how they were placed. Exhuming a body is a process."

The first step is to carefully exhume the remains and number every bone. The next step is to bundle them in tin foil, which is lightweight but still supports the fragile bones. Then, with permission of the Belizean government, the remains are exported to Novotny's lab at Texas Tech for analysis.

Even though the bones are often poorly preserved, Novotny can see some interesting details, such as modifications of the skull and teeth. These modifications were mostly for esthetics, but recent work shows that certain head shapes were more common in the eastern Maya area than the west, suggesting the shapes may have been associated with social identity linked to geography.

Some head shaping was not intentional, like the flattening of the back of the head associated with using a cradleboard for carrying babies, while others were intentional, such as modifying the head to make it look like a cob of corn, the main agricultural crop. Modifications of the teeth included notches, or grooves, and inlays of jade or pyrite.

In 2016, Houk and Novotny were excavating in the acropolis and found what they think was a powerful person buried in a crypt under the plaza floor. The body was found with a jade plaque containing iconography. A similar jade plaque was found by Houk in a royal tomb located not far from the crypt under the same plaza floor. Interestingly, the crypt did not only contain the remains of the person who bore the jade plaque, but those of at least two other people. The remains of one body had been stacked in a corner with the skull carefully placed on top.

Novotny says that many times tomb space would be reused, not because of space limitations but due to mortuary traditions that revolved around ancestor veneration and communicating with the deceased. Continued presence with the remains of their family was important to the Mayan culture, and many believed that even though the biological body dies the life essence, or soul, could still communicate, especially for powerful people in life such as nobility.

To keep these spirits happy and out of trouble in death, friends and relatives would bring their beloved flowers, incense, candles, or food. This is how Mayans communicated with the deceased, and, in some ways, is reminiscent of Dia de los Muertes, which is still celebrated today in the Mexican culture. The ancient Maya left few drawings depicting funerals, leaving the archaeological record as the only evidence of these fascinating rituals.

Novotny is excited to learn more about the ancient Maya leaders of Chan Chich this summer, when she and Houk will take 12 undergraduates and three graduate students to excavate at Chan Chich for five weeks. They will be excavating in the city's acropolis again, and the students may get the unique experience of excavating human skeletal remains. The skeletal remains from Chan Chich will be the subject of several forthcoming master's theses in archeology at Texas Tech.

Discoveries

-

Address

Texas Tech University, 2500 Broadway, Box 41075 Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.3905 -

Email

vpr.communications@ttu.edu