Raptor Research

By: John Davis

Scientists collect golden eagle data to help energy companies make smarter decisions.

Across the plateaus, prairies and plowed fields of cotton, windmills whirr as the wind transforms into clean energy. It's a new energy boom, and Texas' breezy conditions make it a perfect place to catch this renewable power source.

That's great news for humans who want to wean themselves off fossil fuels. But for golden eagles? Not so much.

For whatever reason, these apex predators are one of a handful of birds that are prone to blade strikes, says Clint Boal, a professor of wildlife ecology in the College of Agricultural Sciences & Natural Resources and a raptor expert. Perhaps the blades spin within a preferred hunting altitude. Maybe hunting or flight displays creates tunnel vision, and they don't see the propellers before it's too late. Young eagles on the wing for only a few weeks or months may be too clumsy in flight to avoid collisions, especially on windy days.

It's not just the wind turbines that pose a threat, he says. Electrocutions along power lines, accidental poisonings and outright shootings also play a role.

Most golden eagle deaths are unintentional. However, that can cause legal problems for energy companies as well as private citizens, Boal said. They're not currently considered endangered, but golden eagles share the same legal protection as their bald counterparts. That could mean hefty fines for accidental death due to gross human negligence.

In 2009, the Eagle Act was amended to offer energy companies and others a limited number of permits for accidental deaths in certain situations. In return, permit holders have to do everything reasonable to avoid or minimize chances of killing eagles on their properties and facilities. If an eagle is killed, permitees must somehow prevent the death of an eagle elsewhere for “no net loss.”

That sounded like a fair trade, but it created lots of questions. How would a permitee ensure that another golden eagle would survive? For this species, the area in question is huge, encompassing the entire Western United States smack-dab where energy companies want to develop wind farms. Optimal wind energy resources in West Texas, Southwestern Kansas, Western Oklahoma and Eastern New Mexico overlap a prime habitat area where scientists didn't even know how many golden eagles may be present, calling it a “black hole” for information.

Were bird collisions more likely to occur at wind energy projects in some areas more than others? Where did typical golden eagles go after leaving the birth site? Where were prime hunting grounds? How well did eagles survive, and what were important causes of death?

No one knew for sure.

Recently, Boal partnered with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and other conservation agencies and organizations to try to answer these questions. The group is using satellite telemetry to track golden eagles from fledging through early years of their lives. Already, they have discovered what they call amazing new information in understanding how these golden eagles move after they leave their nest, what areas and habitats are most important to them in the region, and what challenges the eagles face in the first years of their lives. With that information researchers hope to reduce human-caused golden eagle deaths by enhancing habitat and mitigating or eliminating risk factors.

A Wing and a Prayer

It's a grand place to be at the top of the food chain.

It's also a lot of work.

Golden eagles soar up to 15,000 feet across the West Texas skies looking for a meal. With a penchant for prairie dogs, they love to hunt on the South Plains. Perhaps not as popular as their bald counterparts, they've perfectly adapted to their environment. They're powerful hunters preying on a wide variety of animals, and they aren't above scavenging when food is scarce.

The power and beauty of raptors like golden eagles drew Boal to study them. Growing up in Oregon, he said watching the mating flight of red-tailed hawks soaring above the treetops inspired his love of predatory birds.

“You know how some people look at a shark, or tigers or wolves,” he said. “That's how it is with me and raptors. I've always been fascinated with predators. They have a hard life. It's a lot more difficult for a predator to get a meal than for an herbivore.”

Predators tend to mature more slowly as well, he said. It takes five years for golden eagles to reach sexual maturity. They are solitary until they find their mate.

“Young eagles may roam quite a bit during their first few years,” Boal said. “Once they reach sexual maturity at about five years old, they will look for a suitable nesting area that is vacant. Males will then start doing flight displays above the nesting area he's worked on, and he'll try to attract a female. The mating dance of the male is a dynamic roller coaster flight with exaggerated wings beats. It's spectacular to watch. He will eventually dive down to where he's been building on a nest. The male will court the female like that. If it works, she starts hanging out around nest. They'll copulate, and she'll lay eggs. The male does most of the hunting. The female takes care of the nestlings for most part.”

Their offspring grow like wildfire in the first 60 days of life. Perhaps they have a brother or sister next to them in the huge nest built by their father. Usually, though, golden eagles lay but one egg in the spring.

The small number of offspring produced are part of the natural balance of predator to prey. But Boal said this can cause problems if more offspring are taken by human activities than are needed to maintain a stable population.

“In '40s, '50s and '60s, golden eagles in West Texas and Eastern New Mexico were heavily persecuted by trapping and shooting,” Boal said. “Hundreds of eagles were killed each year because ranchers mistakenly thought they were preying on sheep and goats. Well, they may occasionally capture young livestock, but they're scavengers, too, and if they find a carcass, they're going to eat. But many mistook this to mean the eagles were killing the livestock. This led to the golden eagle being added to the Bald Eagle Protection Act in 1962. As to what we know about golden eagle populations around the Trans-Pecos and New Mexico areas, the populations have never recovered.”

Even today, Boal said, some ranchers see the birds as a threat to their livestock because what they've perceived to be hunting is almost always scavenging. However, scientific evidence showed that these eagles mainly eat small mammals, especially jackrabbits and prairie dogs. Despite the scientific evidence, some landowners still misunderstand the birds.

“My goal with looking at ecological questions like this is that we see stuff all the time on the landscape, and we make our own interpretations of it,” he said. “However, our interpretations could be very off base. I want to know what reality is, not what speculation and accusations are. In the '50s and '60s, studies looked into what golden eagles ate. All evidence suggested a huge proportion was cottontails and jackrabbits. Occasionally, they may have a ‘Sunday dinner' of deer fawn or pronghorn, but those are more the unusual ones that catch your attention and are inconsequential. Usually, the larger animals eagles ate were stillborn livestock animals or those killed by other causes and the eagle was taking advantage of it.”

Boal, a member of the United States Geological Survey's Cooperative Research Unit at Texas Tech, along with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Region 2 Office and its Western Golden Eagle Team, have begun tracking golden eagle movements and potential interactions with energy projects.

By day 50, the eaglet is nearing full size and scrambling around and experimenting with his or her wings on the ledge of the cliff face or tree branches that support its nest. It's not long after that they take their first flight. Boal and others in the team hope to catch the eaglet at this stage because, though not quite ready to fly, their bodies are fully grown, which is most ideal for fitting the bird with attaching a satellite transmitter.

The $3,500 transmitter is attached to a special ultralight, super strong harness that is custom-fitted to each eaglet. The transmitter has a small solar panel that recharges its battery. Every hour during the day, the transmitter records the eagle's location to within 20 yards, including height above the ground. The data pass through a satellite uplink so that, by looking at their computers, scientists know exactly how far and where these eagles travel after leaving the nest and forging a life of their own.

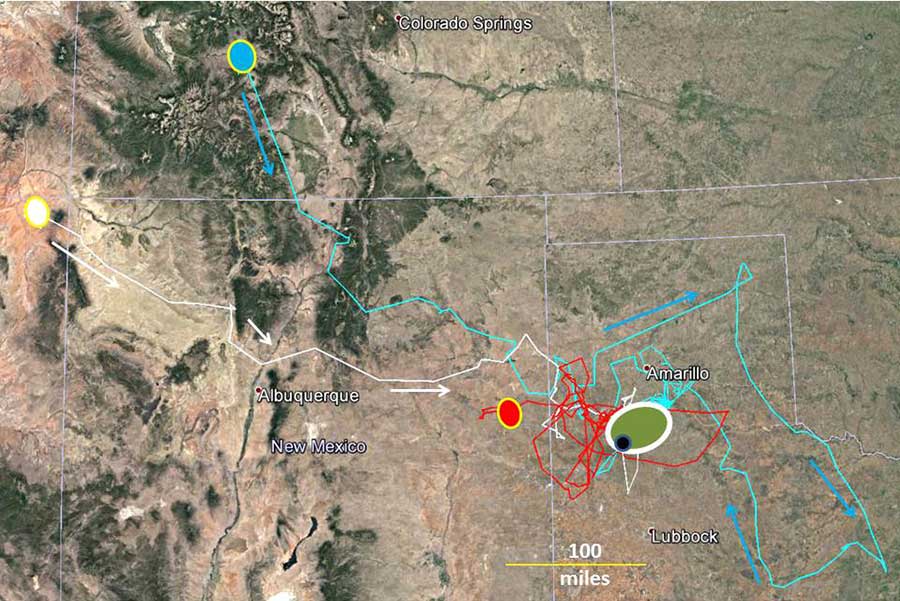

During 2015 and 2016, 22 golden eagles were tagged with transmitters in Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma. Eighty eagles also were tagged in the Four Corners region during 2009-2014. Since that time, scientists have learned a lot about how young birds travel in the first years of life, where they prefer to hunt, how far they're willing to travel to rich hunting grounds, and how human activities impair the birds' ability to survive during the formative years.

By the end of their first year, for example, most young eagles wind up about 25-75 miles from home, in landscapes somewhat similar to areas where they were raised and where their survival is relatively good. But about 15 percent of them move up to 300-900 miles from home during their first year, crossing into new regions. Most of the “travelers” die before their first year, and it's unclear why they would take such risks. Boal believes new genes may serve as the prize for the golden eagles that do survive to breeding age in distant lands.

Observational Power

Something wasn't right with golden eagle No. 121734, a male from a nest near wind energy projects in eastern New Mexico. Despite much time spent flying around wind turbines for several weeks after fledging in mid-summer, the eagle moved about 60 miles from home in September.

On a cold January day, Bob Murphy, a non-game migratory bird biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, studied this bird's movement on his computer in Albuquerque. Murphy and others suspected something was wrong for some time. They hadn't actually seen the bird since fitting it with a satellite transmitter just before the eagle left its nest. But the transmitter data showed the eagle had suddenly limited its movement west of Muleshoe, near the New Mexico state line. Maybe it was scavenging a carcass in a field. Sometimes they do that. But a harsh, 3-day winter storm had passed through the area the week before.

“It sat out the blizzard by perching on ground for 3 days,” Murphy said. “Then it moved only 5 miles in two days. Then for about a week, it moved only 12 miles total and stopped again. We were concerned the bird probably was dead. A New Mexico wildlife law enforcement officer assisted us in finding that one. The first year is a tough time for a young eagle.”

An autopsy showed that the eagle had starved to death. A sad outcome perhaps, but a natural one. By contrast, other data points have shown where eagles have been electrocuted by colliding with power lines, died from poisons, shot, killed by turbine blades, and hit by cars while scavenging; one was even killed by a mountain lion at the carcass of a mule deer.

“We are really interested in where they go after they leave the nest,” he said. “That's important when we try to understand the big picture. It's not uncommon for those young birds to move several hundred miles from their nest that first year.”

Murphy said his group began working with Boal about 10 years ago because he's a well-known, experienced raptor biologist. Initially, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service contracted Boal to do some aerial surveys of golden eagle breeding habitat while looking for eagle nests in Palo Duro Canyon and other areas in Texas.

“That's how we got started in this work in Texas,” Murphy said. “And, that's when the interest and concerns about golden eagles in the western U.S. was really growing. One of big information gaps was the Southern Great Plains and Trans-Pecos regions. We knew of some nests there, but we didn't know anything about eagle movements or their seasonal distribution. We needed to know more than just where the nests were, so we began trying to identify areas of particular importance to younger eagles. For Clint, this was right up his alley. It was a kind of a win/win, a good fit for him working with us. And because of his university tie we've had great students engaged in and handling parts of this project as an added bonus.”

While the eagles they seek can't yet fly, that doesn't mean they can't hop and glide. Murphy said that when attempting to capture eaglets at the nest, groups of 5 or more people spread out below in case a fledgling panics and makes an early flight from its nest.

Murphy said the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service now has a better idea how golden eagle populations are structured and how much the birds typically move between populations. Favorite hunting grounds have emerged as well as the nature of seasonal movement and where migration corridors exist, especially for the golden eagle populations on the Southern Great Plains and Trans-Pecos regions, plus the Four Corners region studied in earlier years.

The group also has been able to contribute significant data to continent-wide studies of golden eagles. One such study shows that human-caused deaths are increasingly important as golden eagles grow older. During the first year of life, about two-thirds of deaths are due to natural factors, mainly starvation and disease. By adult age, however, two-thirds of death are related to human activities. This demonstrates how efforts to decrease human-caused deaths of golden eagles can greatly improve stability of the overall population. Another part of the study confirmed that year-to-year survival of adult eagles is about 90%, quite high for the bird world, while only about 65% of the eagles survive their first year.

Electrocution on power line poles caused many unintentional deaths, the team found. These poles located near prairie dog towns south of Buffalo Lake National Wildlife Refuge near Hereford may involve golden eagles from all points on the map, based on the telemetry data. Some golden eagles that spend winter there come from northeastern New Mexico to central Colorado to northeastern Arizona. The group could advise local energy companies where they should retrofit lines to avoid such electrocutions.

The group has identified high-use sites by golden eagles extending far south of the refuge, where wind energy development could create danger for the eagles.

Murphy said that the study also will clearly document the relationship between where an eagle is raised and where it eventually holds a nesting territory of its own. This is important in understanding how well a local population of golden eagles can tolerate negative impacts. If eagles move far to find their first nesting territory, a population that is decreasing may rebound quicker.

“The information we have gathered in Texas and adjoining areas has been extremely valuable for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in conserving golden eagles,” Murphy said. “We're working closely with the wind energy industry to plan development in areas that pose low risk to golden eagles. The telemetry has helped us considerably in working with industry to place projects in sites less likely to attract golden eagles, where risk to the eagles is low.”

Discoveries

-

Address

Texas Tech University, 2500 Broadway, Box 41075 Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.3905 -

Email

vpr.communications@ttu.edu