Creating Value from Waste

February 19, 2016

A Texas Tech professor's work with low-grade cotton could put more money in producers' pockets and more environmentally friendly products on consumers' shelves.

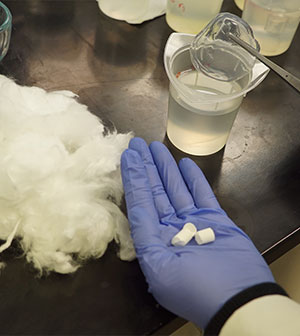

Texas produces about 4.5 million bales of cotton each year representing a $1 billion contribution to the state's economy. Not all that cotton is usable and ends up as no-value or low-value waste. But a Texas Tech University researcher looks at the low-grade, virtually worthless cotton and sees a variety of new, environmentally friendly products that could create new value for cotton producers.

Noureddine Abidi, associate director of Texas Tech's Fiber and Biopolymer Research Institute, grinds the low-grade cotton into powder and then turns it into a gel. It is the gel that presents myriad possibilities and already has yielded two patents for Abidi.

Biomedical Implications

Abidi's work begins with cellulose, a major part of a plant's cell wall that is used

to make a variety of products, such as paper. Because cotton is more than 95 percent

cellulose the potential to develop more environmental and people friendly products

is great.

Abidi's work begins with cellulose, a major part of a plant's cell wall that is used

to make a variety of products, such as paper. Because cotton is more than 95 percent

cellulose the potential to develop more environmental and people friendly products

is great.

Abidi, a textile chemist, has applied for a provisional patent on a process to create cellulose nanocrystals that potentially could replace dyes used in the body during some medical exams.

"We break the cotton down and form cellulose nanocrystals," he said. "We can then separate them based on their size and give them properties to change colors. These nanocrystals could be functionalized and used as markers rather than the dyes currently used in radiological exams. Because the cellulose nanocrystals are a natural product, it is better for the body."

The same color-changing process makes the nanocrystals potentially usable in liquid crystal displays, such as flat screen televisions and digital clocks and watches.

Abidi also is working on a new type of bandage that could ease the wear and tear of adhesive on the skin every time it is removed to check the healing process.

"The cotton cellulose gel is clear, which could have potential applications to prepare transparent bandages," he said. "This allows a doctor to see how a wound is healing without removing the bandage daily. Our next step is to develop a way for the clear bandage to carry a time-released antimicrobial agent to assist in healing a wound and again reducing the number of times the bandage must be removed."

Environmental Impact

Abidi's second provisional patent puts him on the cutting edge of making the 3-D printing

process more environmentally friendly. Currently, petroleum-based resins are used

in the 3-D printing process. The cellulose gel he creates can be dried and shaped

into just about any form, including the polymer material used in the printer.

Abidi's second provisional patent puts him on the cutting edge of making the 3-D printing

process more environmentally friendly. Currently, petroleum-based resins are used

in the 3-D printing process. The cellulose gel he creates can be dried and shaped

into just about any form, including the polymer material used in the printer.

"Our cellulose-based product is environmentally friendly and requires no petroleum products," he said. "They are biodegradable, they will not take up space in landfills."

Abidi is applying cotton's absorbent qualities to his own industry. Texas Tech's Fiber and Biopolymer Research Institute, which is part of the Department of Plant and Soil Science, is focused on research that promotes the use of natural fibers, such as cotton, and on increasing textile manufacturing in Texas. The institute is equipped to take raw cotton through the complete process of creating fabric.

Abidi said he was struck by how much excess dye is produced by the textile process. And that led him to one of the main uses of his cotton-based gel. The gel can be turned into 100 percent cotton filters that can absorb textile dyes.

"The textile industry produces a lot of effluents that end up in the environment. The material we produce can absorb the dye from the water before it is drained away into the environment," he said.

The same filters also can be functionalized to remove bacteria and oil from water and to filter pollutants from the air.

Abidi's close work with textiles, especially wrinkle-prone cotton, has him looking at new chemical applications to make fabric stain and wrinkle resistant. His goal is to develop a process that will require less water and detergent to clean the fabric and less heat to dry it, making both processes more energy efficient.

He also is part of a research project, funded by the Wal-Mart Foundation, looking at using foam rather than water to apply indigo dye to denim yarns. The project could eventually reduce the amount of water, time, labor, floor space and expense required to apply indigo dye. By reducing the amount of water used, a foam process would be more ecologically friendly.

Working in the Cotton Patch

Abidi, who has received about $12 million for his research since coming to Texas Tech, trained as a polymer chemist. Polymers occur both naturally as with cotton, or can be produced in the laboratory to make substances such as plastic. Polymers are a group of small molecules that when repeated form a larger molecule. Cellulose is a polymer.

"I am fascinated by cellulose and how nature makes a product, as opposed to how a polymer is created by a chemist," he said. "While nature creates fibers, it takes a lot of chemistry to create the fabrics that we use every day. That led me to focus on textile chemistry."

Abidi, a native of Morocco, has earned degrees in his home country and in France. During the spring 2016 semester he is taking his cotton fiber research to Belgium as part of a Fulbright Grant from the Council for International Exchange of Scholars. He is spending five months at Ghent University focusing on teaching and research.

The Fulbright is the latest success for Abidi since he came to Texas Tech 17 years ago. He meant to stay only a year, but the research opportunities, and working in the heart of the largest cotton patch in the world changed his mind.

"I came here from France as a postdoctoral research fellow in 1999 and was only going to stay a year, but working at Texas Tech is interesting," he said. "I work in an area where cotton is everywhere. I can almost walk outside and grab a handful and start to work."