Cultural Norms in the United States

Culture in the United States may differ greatly from the culture in your country. For example, food will bevery different from what you are used to at home, and personal relationships may develop at a different pace. Please remember that an integral part of your Fellowship is your experience of U.S. culture, so try toremain open-minded to these new experiences!

International visitors often find the United States diverse, although the level and

type of diversity varies between cities, states, and urban and rural environments.

Visitors may need time to adjust to U.S. culture.

Cultural Norms in the United States

Cultural norms may differ greatly from those in your country. U.S. cultural norms

can include individualism,

equality, informality, punctuality, and directness. Specific examples of these norms

and values include:

• Working Days and Hours – The work week in the United States runs Monday through Friday, with Saturday

and Sunday as weekend days. Typical working hours are 8:00 am to 5:00 pm (08:00-17:00),

though some

activities may start earlier or end later. You are expected to fully participate in

the Fellowship, regardless

of the day of the week on which activities are planned. This may mean participating

in activities on a day

you would normally have free in your home country. Please reach out to your Institute

staff if you have

questions about activities that may conflict with specific holy/sacred days.

• Punctuality and Attentiveness – Punctuality is important in the United States and a sign of respect. If you

are going to be more than a few minutes late for a personally scheduled meeting due

to circumstances

beyond your control, you should contact the person with whom you are meeting as soon

as possible. You

are expected to be attentive during both formal and informal meetings.

• Typical Greetings – Upon meeting someone for the first time, it is common in the United States to shake

hands in a formal manner and use titles like “Mr.”, “Ms.”, or “Mrs.”; they may switch

to first names soon after

meeting, even with people of different ages, occupations, or social statuses. Someone

may greet you by

saying “How are you doing?” as a way of saying hello, but they do not expect a lengthy

answer; a simple

“fine” or “well” is an appropriate response. Conversations may seem direct and impolite,

but they do not

intend to act disrespectfully.

• Speaking Distance – You may find that people in the United States maintain a greater distance from

one

another than people in other countries. Only good friends and family members hug or

kiss one another.

You should greet others with a handshake rather than a kiss if you do not know them

well. Due to the

COVID-19 pandemic, it has been common practice for people to stand at least six feet

apart from each other

to maintain a safe distance, and handshakes have become less popular to avoid touching.

Follow the lead of whomever you are meeting—if they are standing far away, maintain

your distance. Only engage in a

handshake if they extend their hand.

• Clothing – Although clothing standards vary widely, U.S. students generally wear informal clothes

like jeans

and athletic shoes. Business and government employees tend to dress more formally.

Your Institute will

provide guidance on what is typical on your campus and in your local community, but

you should plan to

bring both casual and professional attire.

• Face Masks – While most places no longer require the use of face masks, you may encounter masking

requirements for certain events or indoor spaces. You should have a mask available

in case you need to

enter a space where one is required or expected

Diversity in the United States

People in the United States value diversity, which varies within and among cities,

states, and urban and rural

areas. During the Fellowship, you will encounter many forms of diversity, including

ethnic, political, religious,

gender, and socioeconomic.

The U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs strives

to ensure that its efforts

reflect the diversity of U.S. society and societies abroad. The Bureau seeks and encourages

the involvement of

people from traditionally underrepresented audiences in all its grants, programs,

and other activities and in its

workforce and workplace. Opportunities are open to people regardless of their race,

color, national origin, sex,

age, religion, geographic location, socioeconomic status, ability, sexual orientation,

gender identity, or any other

protected characteristic as established by U.S. law. The Bureau is committed to fairness,

equity, and inclusion.

The United States takes discrimination very seriously, and U.S. law prohibits discrimination

based on

age, disability, gender, national origin, pregnancy, race/color, religion, and sex.

Many states also prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation. During your

participation in Fellowship activities, you should never use derogatory language,

name-calling, racial slurs, or language that someone could find offensive.

If you have questions about what might constitute discrimination, or if you feel that

you have been a victim of

discrimination during the program, please contact your Institute staff or an IREX

representative immediately.

U.S. views on diversity and tolerance are reflected in our anti-discrimination laws

for the workplace.

For more information on these laws, please visit www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/index.cfm.

In addition, the U.S. Census is an excellent resource on racial and ethnic diversity

in the United States:

www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/00.

Religious Identitiy

The United States promotes freedom of religion and religious tolerance and protects

those with and without

religious beliefs through a secular government. Religion is not a topic typically

discussed when people first

meet in the United States, especially in professional settings, as religious beliefs

are considered a private matter.

Institute staff can provide insight into the main religious groups in your host community.

To learn more about

religion in the United States, visit www.pewforum.org/category/publications.

Worship and Prayer Accommodations

People in the United States observe many different religions, some of which may be

unfamiliar to you. It is

important to approach new contacts with an open mind and with respect for other beliefs.

Please note that despite this diversity, certain religions and sects are more prevalent

in some areas of the country than others.

Institute staff will be aware of any religious preferences indicated on your pre-Institute

survey and will make

every effort to accommodate your needs, including recommending houses of worship either

on or close to

campus if you wish to observe regularly throughout the program.

Please reach out to your Institute staff if you

have questions about activities that may conflict with specific holy/sacred days.

Institute staff can also assist

in finding alternate or private spaces for worship if there is not an organized house

of worship available for your

religion.

We have included a reference list below for worship services and we look forward to

working with you

to identify a place for you to connect while you are with us.

*indicates the walking distance from Carpenter/Well

Buddhism

- Bodhichitta Kadampa Buddhist Center | 6701 Aberdeen Avenue |

- *St. Elizabeth University Parish | 2316 Broadway Street |

- Holy Spirit Catholic Church | 9821 Frankford Avenue |

- Our Lady of Grace Catholic Church | 3111 Erskine Street |

- St. Andrew Greek Orthodox Church | 6001 81st Street |

- St. George Coptic Orthodox Church | 5402 Quaker Avenue |

- Experience Life | 1313 13th Street |

- *First Baptist Church | 2201 Broadway Street |

- *First Christian Church | 2323 Broadway Street |

- Raintree Christian Church | 3601 82nd Street |

- *St. John's United Methodist Church | 1501 University Avenue |

- Hindu Temple of Lubbock | 1400 84th Street | http://www.hindutempleoflubbock.org/

- Islamic Center of the South Plains | 3419 La Salle Avenue | http://www.lubbockmuslims.com/

- Congregation Shaareth Israel | 69282 83rd Street | http://csitemple.org/

Gender Interactions and Sexual Respect in the United States

In the United States, all people enjoy equal opportunity and equal protection from

harassment both under

the law and in practice. Gender relations may appear to be more informal than in your

country; however, all

Fellows are expected to behave respectfully to all other Fellows, Institute staff,

and community partners they

may interact with during the Fellowship. Regardless of gender, people in the United

States commonly form

friendships with no expectation of sexual or romantic relations. Honesty and clear

communication can prevent

confusion about the level of intimacy and expectations in a relationship. You should

never assume that another

person wants an intimate relationship unless they explicitly say so.

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment means making sexual advances toward a person from whom you do not

have consent. The

The United States takes sexual harassment very seriously. Sexual harassment includes

non-verbal, verbal, and

physical forms of unwanted attention, and can occur over email, text messages, and

other electronic forms.

Examples include making sexual jokes, repeatedly commenting on someone's gender, or

sending pornographic

images to someone. If someone tells you that your behavior makes them uncomfortable,

you must stop

the behavior immediately. Keep in mind that sexual harassment in the United States

is determined by the

perception of the person on the receiving end of speech or an action, not by the intention

of the other person.

Harassing speech or behavior toward any individual, sexually or otherwise, may be

grounds for termination

from the Mandela Washington Fellowship as outlined in the signed Terms and Conditions.

If you have questions

about what might constitute sexual harassment, or if you feel that you have been a

victim of sexual harassment

during the program, please contact your Institute staff or an IREX representative

immediately.

For more information on sexual harassment please visit https://www.eeoc.gov/sexual-harassment.

Additional

information on gender identities and the importance of consent is reviewed in the

Gender Relations and Sexual

Respect module on Canvas.

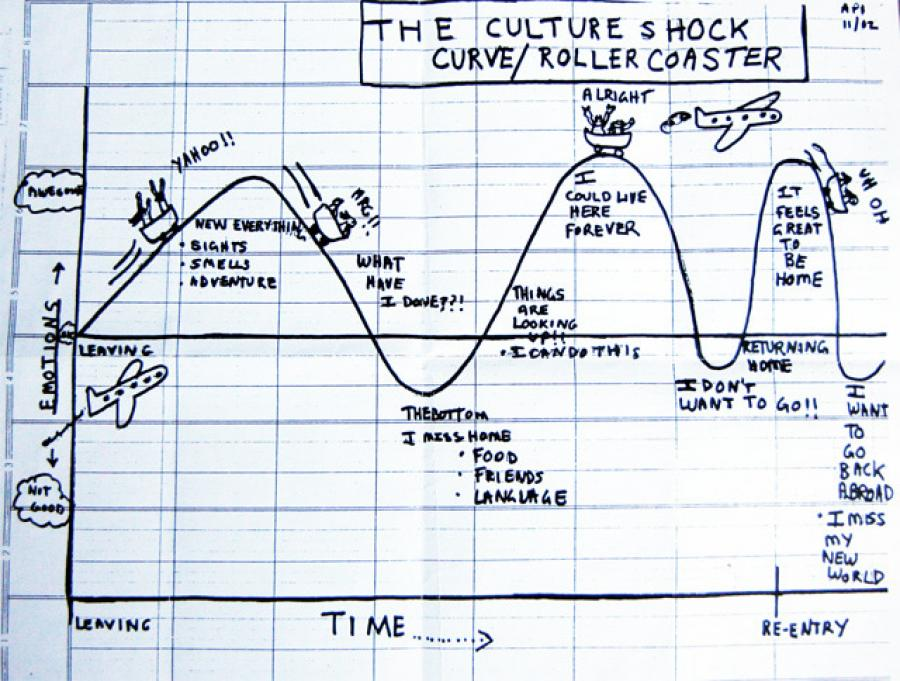

Cultural Adjustment

When traveling to a different place, it is natural to

undergo a cultural adjustment process. You will leave

your family and friends for an unfamiliar environment,

but you will make new friends and gain new and

invaluable experiences as a Mandela Washington

Fellow. Many people use the cultural adjustment

curve to describe the emotional experience of

traveling to and living in a different culture.

The main phases along the curve include honeymoon, crisis

(culture shock), recovery, and adjustment.

When you first arrive at your Institute, you may experience the euphoria or initial

excitement phase (also known

as the honeymoon phase). You will feel excited, interested, and optimistic about your

time in the United States.

After the euphoria phase, you may enter the crisis phase, also known as culture shock.

You will notice the

differences between your culture and your host community, and you may find it difficult

to adapt to U.S. culture

and life. In the recovery and adjustment phases, you will begin to feel more at home

in the United States and will

adopt certain aspects of the new culture while still maintaining your way of life.

In the mastery phase, you will

learn to live comfortably in the United States.

At the completion of the Mandela Washington Fellowship, you will return to your country

and may experience

the cultural adjustment process again (also known as reverse culture shock). Your

experience with cultural

adjustment in your host community, however, may help you cope and resume your life

at home. Each person

experiences the culture shock curve in different ways and at different paces, and

some people may not

experience all phases. Some people find it helpful to set aside quiet time for reflection

or to connect with family

members at home, while others prefer to engage with their new community for support.

FURTHER RESOURCES

• Cultural Adjustment: A Guide for International Students, Counseling and Mental Health

Center at

The University of Texas at Austin

cmhc.utexas.edu/cultureadjustment.html

• Adjusting to a New Culture, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs

exchanges.state.gov/non-us/adjusting-new-culture

• Dealing with Reverse Culture Shock, InterExchange

www.interexchange.org/articles/visit-the-usa/reverse-culture-shock

• 5 Ways to Cope with Reverse Culture Shock, USA Today

www.usatoday.com/story/college/2015/07/29/5-ways-to-cope-with-reverse-culture-shock/37405109

Food & Institute Dining Arrangements

U.S. cuisine varies by town, state, and region, and we encourage you to explore these

differences. While you may

not find foods that are most familiar to you from home, you will find a wide variety

of food available to you in

restaurants, grocery stores, and your host institution's dining facilities.

INSTITUTE DINING ARRANGEMENTS

Dining arrangements vary among Institutes; as such, you will need to be flexible as

you adjust to your new

environment. You should anticipate eating many of your meals in a cafeteria setting,

where options may be

limited, and meals are prepared for large numbers of people. Food served in campus

dining facilities will be

different than what you normally make in your own home and may contain more salt,

sugar, or fat than your

typical diet.

African food will most likely not be available, so you may want to bring a bottle of your favorite sauce, condiment,

or spices to add familiar flavors to meals on campus. Halal and kosher meat may not

be available in all locations, but vegetarian and/or fish options will be. Additional

funds for meals will not

be provided, but you may use some of your stipend money for snacks and other food

items.

Institute staff will be aware of any dietary restrictions indicated on your pre-Institute

survey and will make every effort to

communicate those needs to dining services management.

In addition, many Institutes have housing accommodations that include access to shared

kitchens or may

arrange for Fellows to purchase groceries and prepare a number of group meals. These

meals are a great way for

Fellows to share their cultures with each other and, in some cases, with Institute

staff or community members.

Typical US Meal

Food in the United States will be very different from the food you are accustomed

to at home. You may find

it challenging to adjust, just as a U.S. visitor to your country might experience

similar challenges. Openmindedness and flexibility will make the adjustment easier.

Although there are regional differences, typical U.S.

meals are as follows:

• Breakfast may be smaller than you are used to. “Cold” or “continental” breakfasts

with pastries and coffee

or tea are common at meetings. If you want a hot breakfast, you may need to plan for

extra time in the

morning to prepare or obtain your meal.

• Lunches are often meant to be quick and therefore consist of cold sandwiches and/or

salads that can be

taken to go, rather than hot dishes.

• Dinners are generally served hot and are typically the largest meal of the day.

Dinners may contain a meat

dish and a vegetable dish, plus sweets or fruit for dessert.

Dining in the United States

Dining out is common in the United States, but the frequency depends on a person's budget and/or

amount of

free time. Dining out, particularly at sit-down restaurants with table service, can

be expensive if done frequently.

As portion sizes are usually large, it is common to ask for a “to-go” box to take

home any uneaten food.

Menus in the United States may be different from what you have at home. Appetizers are

small to medium portions that

are equivalent to a starter or first course, while entrees are the main dish. Some

entrees may not come with

anything other than meat or fish, so side dishes are small portions of vegetables

or starch that you can order

for an extra charge. Cocktails contain alcohol and do not refer to a mixture of fruit

juices.

Americans typically split the bill when dining with a group—sometimes each person

pays the exact amount of

their meal, and sometimes the bill is divided evenly if the amounts are very similar.

If a person invites you to

coffee or to a meal, it does not mean that they will pay for your order unless they

directly offer to do so.

Tipping is customary in the United States at sit-down restaurants where you are served by

a waiter. 20% of the

bill before tax is common, but you may tip more or less depending on the quality of

service. Sometimes a tip

or service charge/gratuity will be included automatically if you are with a large

group (usually more than five

people) and will be noted on a receipt. Tipping is not usually expected at fast food

restaurants.

Reservations – Making a reservation at a restaurant is like any other appointment, you are expected to arrive at the scheduled time. If you are running more than 10 minutes late, call the restaurant to let them know. This will ensure that they keep your reservation and avoid giving your table to another party.

Fast food etiquette – When ordering food at a counter, there's typically a queue to place your order. Be sure to wait your turn as it is considered rude to cut in the line or go ahead of someone who has been there before you. Before you reach the counter, have a good idea of what you're going to order. If you're unsure, step aside and allow the person behind you to place their order.

Sharing food – Americans generally do not share dishes, although they may have food at the same time around a table. This may depend on the familiarity of those you are dining with, but in most cases, you'll order your own dish.

General table manners – Most meals are eaten with utensils, although there are some exceptions, such as sandwiches, pizza, french fries, and chips. If unsure, look around to see how others are eating. Another potential faux pas is blowing your nose at the table, as it's considered impolite. Try to excuse yourself and use the restroom or somewhere away from those who are dining.

If you are ever in a situation where you are unsure of what's acceptable, take a look

at the people around you, how they order or what they are eating. As you will discover,

ordering food at the food trucks at is a much different experience than eating at a restaurant but don't let dining etiquette stand in the way of you and a tasty new meal. You can

avoid future awkward misunderstandings with a basic understanding of culture and etiquette

so you can spend more time enjoying your new experiences with confidence.

Dining at someone's home

Whether it's a backyard BBQ, a child's birthday party, or a dinner party for 10, it's an exciting occasion when your new American friend invites you to their home. When it comes to the etiquette of visiting and sharing a meal, it's important to remember that the United States is made up of many different cultures and there are no set rules to follow. Even regionally, you may find a different variation of what's appropriate. To help navigate, just ask your host. Don't feel embarrassed to ask, “What can I bring?” or “What should I wear?” if you're uncertain.

Seating arrangements for this type of setting are generally casual. Your host may tell you where to sit or welcome you to sit wherever you choose. The head of the table is most often reserved for the host, but the other seats will be available for your choosing. Table manners are casual but polite in the home. Just follow your host's lead, and you'll be just fine!

Information from https://usvisagroup.com/american-table-manners/

Email Etiquette

Email etiquette is very important, particularly when initiating connections with a

wide range of professional

contacts from different countries. Clear and direct communication ensures that everyone

has the same

understanding. Always communicate in a professional manner when corresponding with

staff from your

Leadership Institute and other partners. All emails and other correspondences should

begin with “Dear Mr./Ms.

Last Name/Surname” unless you are communicating with someone you know well. Be polite

and use common

sense, and if you are unsure of how to word an email, ask Leadership Institute staff.

If you are requesting action or assistance, be as specific as possible, including

the times by which you need the

information. Planning ahead will be critical to maximizing networking opportunities

during your Fellowship,

which makes it even more important that your emails to colleagues and staff are clear,

specific, and concise.

Professional email example:

Dear Mr. Smith,

On August 12, 2023, IREX will be hosting Dr. Peter Peterson, Secretary-General of

the Global International

Organization. Dr. Peterson will be leading a policy discussion on United Nations missions

in Africa and

transatlantic economic issues. IREX would like to extend a warm invitation to you

and a guest to attend this

exciting event. Dr. Peterson's biography and additional information on the event is

below. Please contact Ivan

Ivanov at iivanov@irex.org to RSVP or to ask questions.

Best,

Mark Marcus

He/him

Program Associate | IREX

1275 K Street, NW, Washington, DC 20006

Tel: 202-628-8188 | mmarcus@irex.org

www.IREX.org

Learn more email etiquette tips in the

English as a Second Language, Part II:

Practical Professional Skills course in

Leading in a Changing Paradigm on the

Fellowship Portal.

https://mwfellowship.instructure.com/

courses/152

Mandela Washington Fellowship Program

-

Address

601 Indiana Avenue, Lubbock, TX 79409-5004 -

Phone

806.742.3667 -

Email

michael.johnson@ttu.edu