Engaging Folsom (10,800-10,200) Hunter-Gatherers with 3D Technologies

Folsom hunter-gatherers (10,800-10,200 radiocarbon years) are the first people on the Plains of North America with an economy focused on bison hunting. These early Native Americans traveled hundreds of miles on foot in pursuit of bison herds, and they developed some of the most sophisticated stone tools known for the New World.

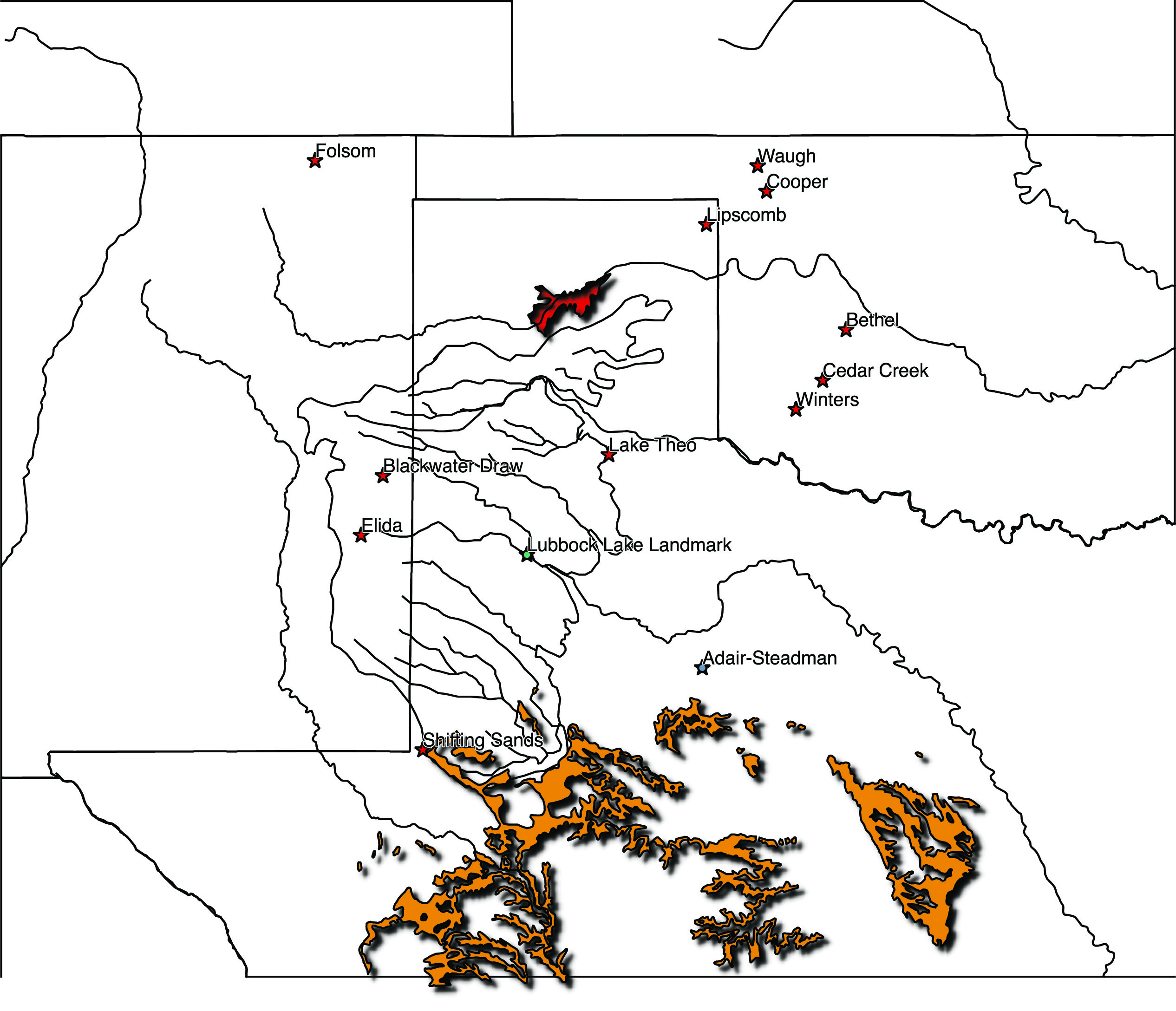

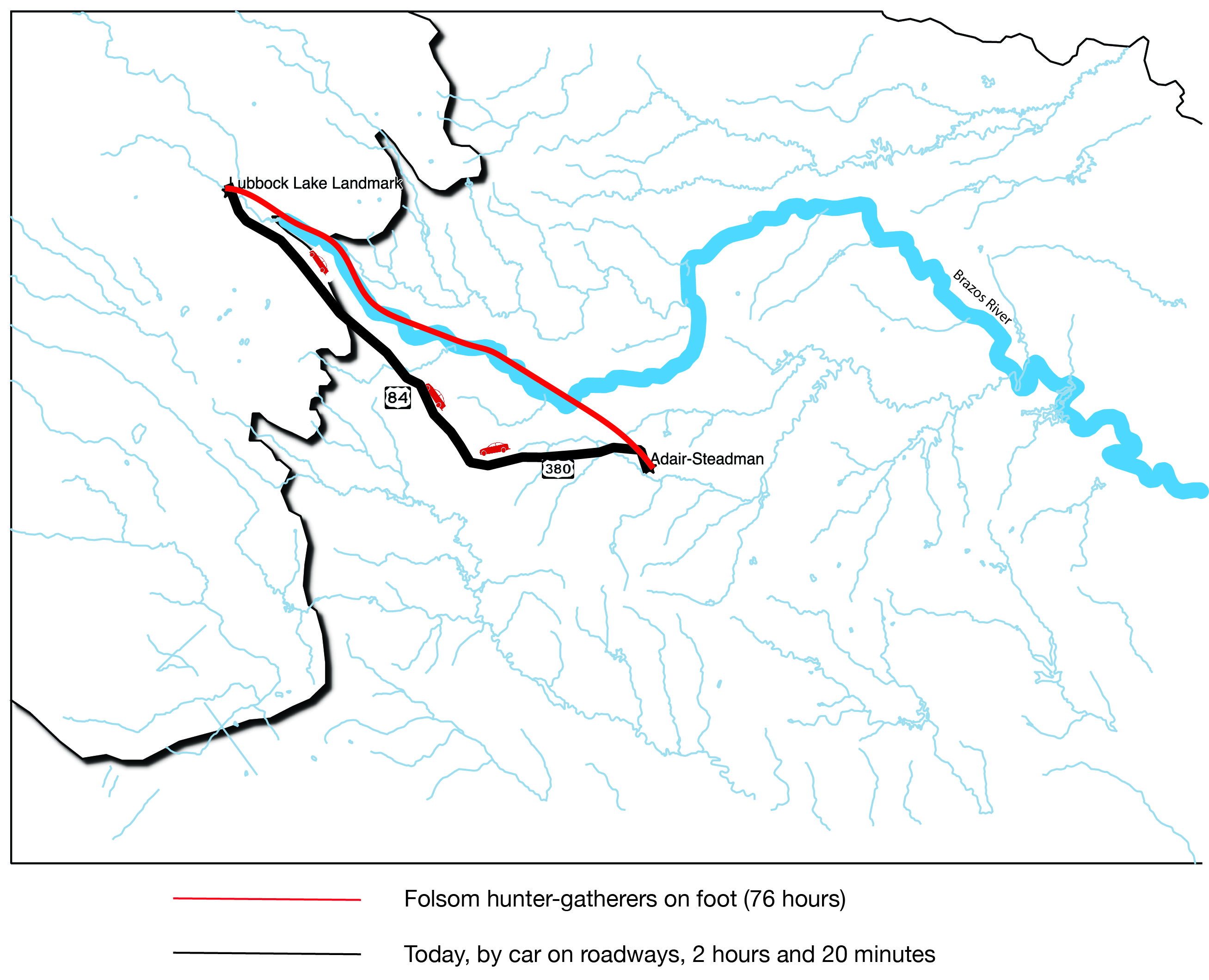

On the Southern Plains, Lubbock Lake and Adair-Steadman are located in the Brazos River basin. Adair-Steadman is 119 miles (192 kilometers) downstream from Lubbock Lake. Investigations at the Landmark have uncovered a series of Folsom bison kills and butchering areas, and at Adair-Steadman a stone tool workshop.

From Adair-Steadman to the Landmark, Folsom lithic technology, mobility, and bison hunting are explored across the Southern Plains through 3D technologies.

Folsom in 3D

Rapid advancements in 3D modeling and 3D printing are creating new and interactive ways to visualize and touch what life was like in the past. Most objects in this exhibit are replicated via 3D printing. You are welcome to touch, pick them up, and photograph them. On some of the objects you will notice braille. One major advantage of 3D printing is the ability to expand accessibility with the incorporation of braille onto objects.

The Exhibit

This project was supported by a grant from the Community Fund of the Community Foundation of West Texas.

Established in 1981, the Community Foundation of West Texas is a regional philanthropic entity created by and for the people of the Texas South Plains region. The Community Foundation exists to improve quality of left in this region by helping area donors to give in ways that make an enduring impact on their community. In 2015, the Community Foundation and its affiliates awarded more than $1.7 million in grants and scholarships, funding projects of hundreds of nonprofit organizations, schools, and government agencies. Visit Community Foundation of West Texas to learn more.

Folsom Archaeology

A major controversy in archaeology prior to 1926 was whether Native Americans migrated to the Americas before the end of the last ice age approximately 11,000 years ago (radiocarbon years).

The Folsom site originally was discovered in 1908 by George McJunkin, an African-American cowboy. McJunkin noticed large bones eroding out of the arroyo after a big flash flood that exposed the ancient kill. He brought the site to the attention of local amateur natural historians in Raton, New Mexico who eventually contacted Harold Cook.

Cook and Jesse Figgins, researchers from the Colorado Museum of Natural History in Denver, led excavations that documented stone projectile points were used to kill an extinct form of bison (Bison antiquus) in Wild Horse arroyo located in northeastern New Mexico. The site was named the Folsom site after the nearby town of Folsom, New Mexico and the associated previously unknown points were termed Folsom projectile points.

The Folsom site discovery was the first to demonstrate that Native Americans were present at the end of the last ice age. Just 10 years later, Folsom points and ancient bison remains were discovered at what is now known as the Lubbock Lake Landmark. For decades afterward, Lubbock Lake was known primarily as a Folsom site.

Today, over 14 Folsom sites have been identified across the Southern Plains of North America. Radiocarbon ages indicate that Folsom sites date between 10,800-10,200 years old and represents one of the oldest time periods of hunter-gatherers in North America.

After the Folsom discovery, E.B. Howard and John Cotter, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania Museum and Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences , led field work that documented a different style of projectile point used to kill mammoths stratigraphically below and older than Folsom along Blackwater Draw in New Mexico. These points were named Clovis projectile points after the nearby town of Clovis, New Mexico. Clovis sites across North America have been radiocarbon dated to 11,500-10,800 years old. Clovis also is represented at the Landmark as are more recent Paleoindian peoples that came after Folsom.

Folsom at Adair-Steadman – An Edwards Formation chert stone tool workshop

Adair-Steadman is located on a terrace north of the Clear Fork of the Brazos River and near a spring that flowed during Folsom times. Chert from an Edwards Formation gravel quarry was carried 3.12 miles (5.03 kilometers) to Adair-Steadman for making stone tools.

Adair-Steadman took its name from the landowner and the person who discovered the site. Foy Steadman, a local postal delivery person, found the site in the late 1960s and brought it to the attention of the landowner Link Adair and the Texas Historical Commission. Curtis Tunnell, at the time the Texas State Archeologist, was the original investigator.

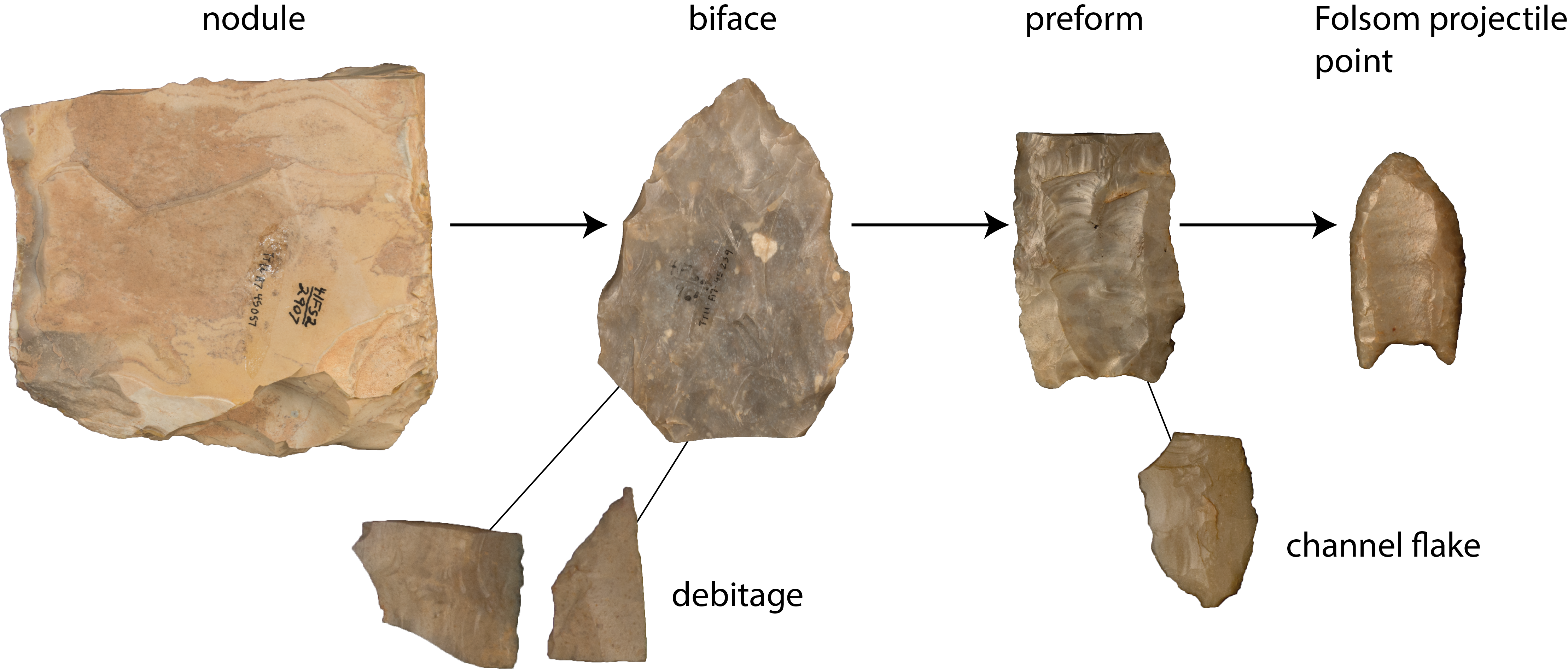

Over 45,000 stone tools and debitage were recovered during this work. With the discovery of Folsom point preforms, channel flakes, and projectile points, Tunnell was the first to decipher how Folsom flintknappers made Folsom projectile points. Adair-Steadman was the first known workshop for making Folsom points.

The Lubbock Lake Landmark research team renewed investigations at Adair-Steadman in 1999. Annual surveys and test excavations are uncovering additional stone tools and debitage that provide more information about activities at the site. Examination of objects from the original investigation is ongoing to add new information on Folsom flintknapping activities at the site.

The Process of Flintknapping

Making stone tools is a reductive process. Stone tools are fashioned from removing rock by controlling how the rock fractures.

A hard or soft hammer are used to directly strike the stone at angles 90 degrees or less. Flintknappers often prefer the use of soft hammers fashioned from antlers to produce wider and flatter flakes

Flintknappers rely upon pressure flakers made from antler tines in the final stages of crafting stone tools. In this case, the pressure flaker is directly pressed into the edge of the stone and with a downward motion a more narrow flake is removed from the rock’s surface.

Folsom Lithic Technology “thinner is better”

Folsom hunter-gatherers relied upon flaked stone for making cutting, scraping, drilling, piercing, and projectile tools. An important consideration in crafting stone tools was minimizing the amount of flaked stone weight carried across the landscape. Folsom flintknappers excelled at making extremely thin bifaces and projectile points for minimizing weight while maximizing the amount of potential tool uses.

Bifaces are multifunctional tools similar to today’s Swiss army knife and useful in three different ways

- Bifaces can be used as cores for driving off thin and sharp flakes useful as tools themselves or for further reduction into other tools types.

- Bifaces are great handheld tools for butchering and cutting tasks

- Bifaces themselves can be reduced further into other tools types such as projectile points or knives.

Folsom flintknappers made extremely thin bifaces known as ultra-thins. Ultra-thin bifaces had a width-thickness ratio of 8 to 1 or greater. Making ultra-thin bifaces required a lot of skill to not break the bifaces in half while removing thinning flakes. Ultra-thin bifaces were light weight, portable packages for supplying raw material for making tools, and used as tools themselves.

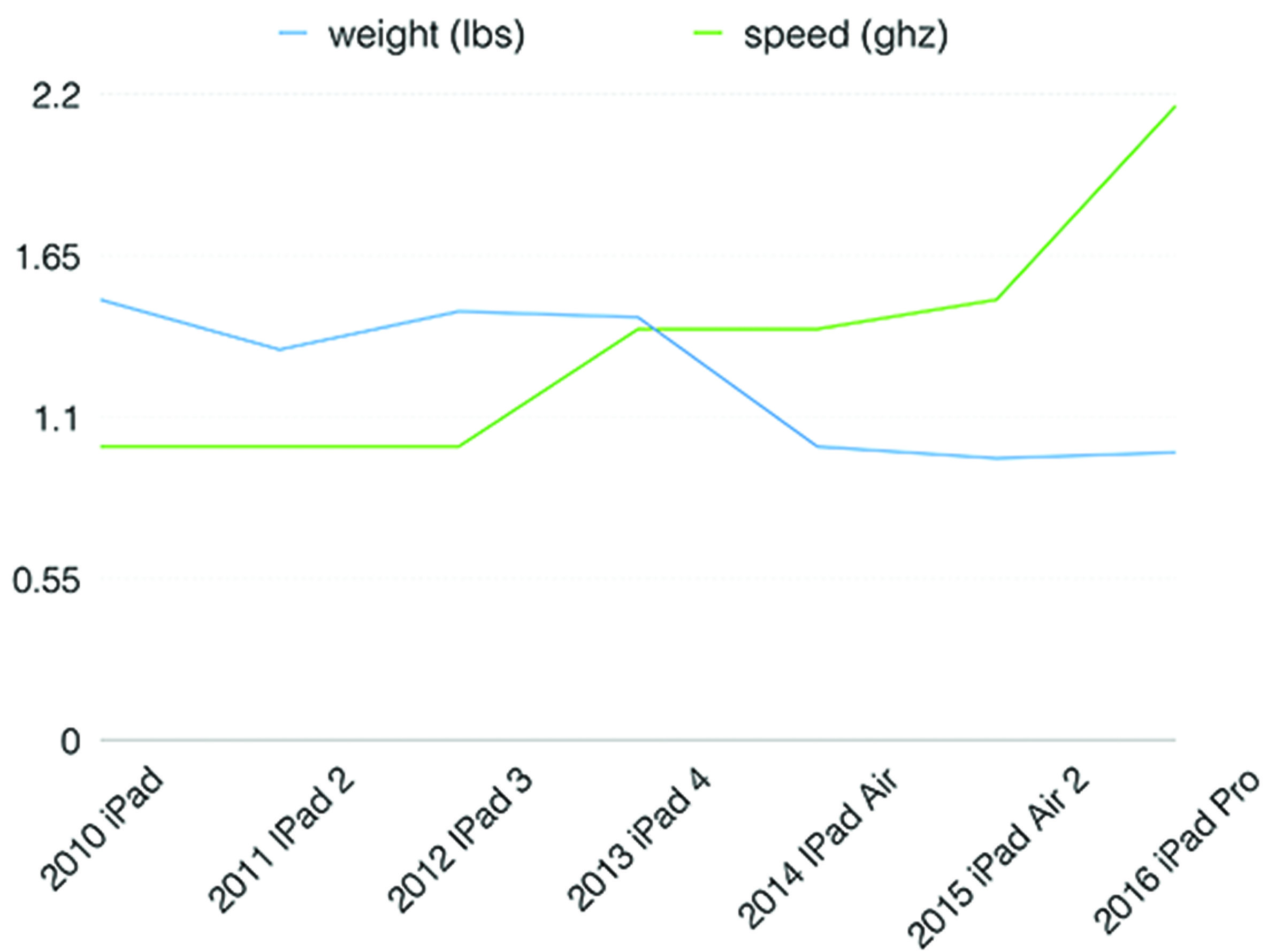

Making objects that are light and portable as possible without giving up usefulness is still common today. For example, each generation of tablet computers have become thinner to decrease weight while increasing computing power

Folsom Lithic Technology - Folsom Projectile Point

Press play on the model to explore a Folsom Projectile Point in 3D

You can drag and rotate the Folsom Projectile Point to see it at all angles. At the physical exhibit, models are printed so that visitors can handle them.

Skip 3D modelFolsom Projectile Point

Folsom flintknappers made extremely thin projectile points by fluting one or both sides of the biface.

Folsom flintknappers broke their intended Folsom point while fluting 1/3 of the time. Although fluting was risky, Folsom flintknappers desired the thinnest projectile point possible.

Fluted Folsom points were hafted to near the tip, only exposing the outer edges of the point. When the tip was fractured from impact, the point was slid up like a utility knife, resharpened, and reused.

Lithic technology experts Stan Ahler and Phil Geib concluded after a detailed study of Folsom point technology in 2000:

‘‘We believe that the Folsom point was one of the most reliable big game hunting tips ever made. It was reliable because its design ingeniously combined features of thinness, extremely sharp leading edge, and low haft drag to create a weapon with deep cutting and penetrating capabilities”

Press play on the model to explore a Folsom Preform in 3D

Skip 3D modelFolsom Preform

Press play to listen, or read the transcript to learn more about folsom preforms.

Press play on the model to explore a Folsom Ultrathin Biface in 3D

Skip 3D modelFolsom Ultrathin Biface

Press play to listen, or read the transcript to learn more about ultrathin bifaces.

From Adair-Steadman to Lubbock Lake Landmark – Folsom Moving on the Landscape

From workshops like Adair-Steadman, Folsom hunter-gatherers carried their tools with them on foot across the Southern Plains hundreds of miles, regularly stopping at the same places to hunt bison. Lubbock Lake was one of the places Folsom people hunted and butchered bison along the marshy ponds in Yellowhouse Draw.

Today, people travel across the landscape in cars following a network of roads that interconnect towns and cities. In the past, rivers were the highways people followed that provided water, food, and acted as the landscape’s sign posts for direction.

Folsom Mobility Hunting Ancient Bison

Folsom hunter-gatherers moved great distances to follow herds of ancient bison.

In comparison to modern bison, ancient bison is approximately 30% larger in size and had horns that projected more to the side rather than curving up towards the top of the head. Ancient bison was adapted to cool season grasslands and likely lived in smaller size herds. The changeover from the ancient to modern form occurs sometime between 8,000-6,500 years ago, and, most likely, around 7,000 years ago.

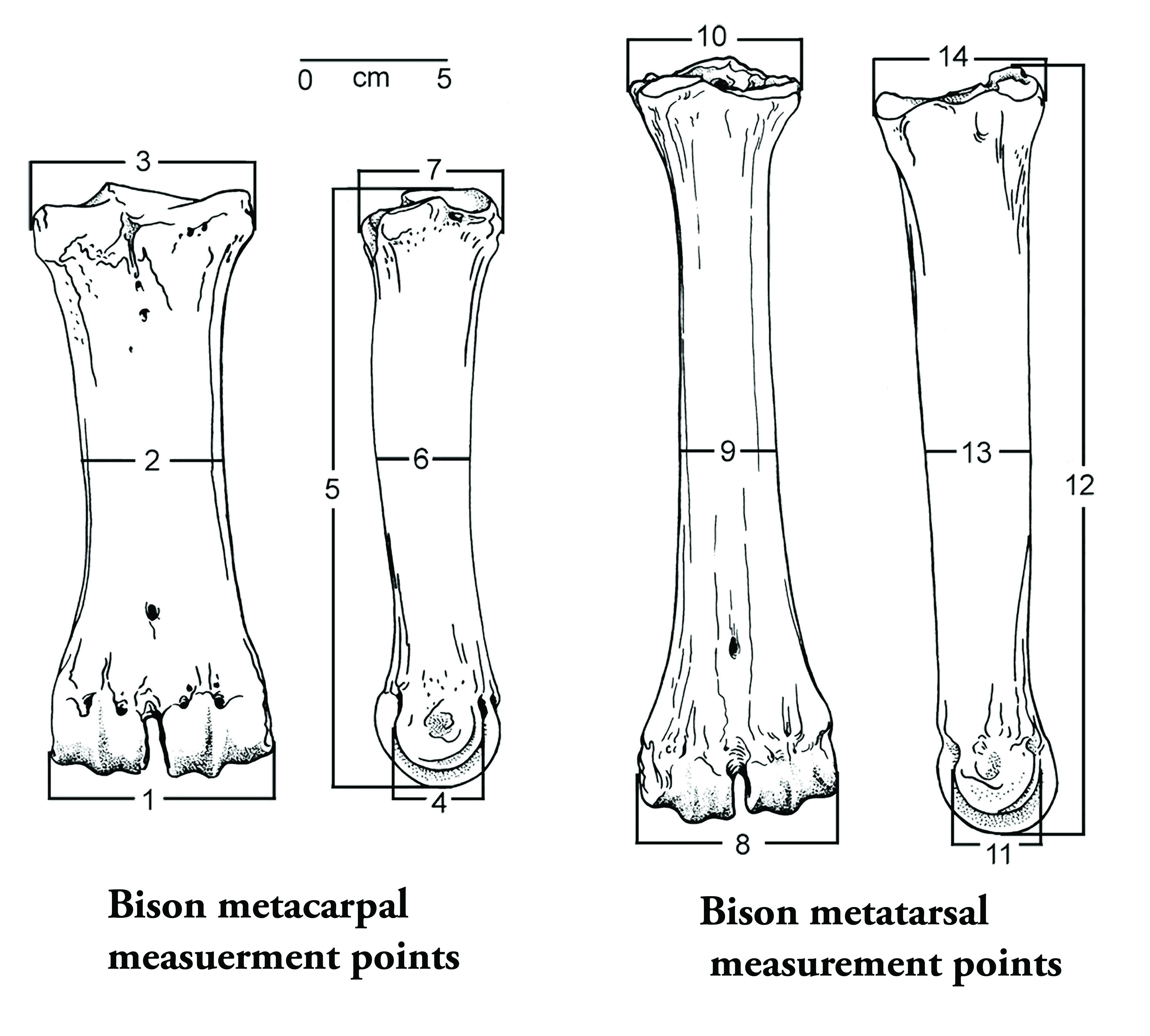

Changes in past animals species can be examined through detailed studies of their bones. Metapodials are a key element used to understand the nature of changes in bison.

Metapodials preserve well in the geological record and reflect changes in bison anatomy. Metapodials become smaller in size and the outer bone wall becomes less thick through time. These findings indicate a change in bison size and movement patterns during the last 11,000 years.

Press play on the models to see the difference between Bison bison and Bison antiquus Metatarsals in 3D

You can drag and rotate the metatarsals to see them at all angles. At the physical exhibit, models are printed so that visitors can handle them.

Skip 3D modelsBison bison Metatarsal

Bison antiquus Metatarsal

Modern and Ancient Bison Bones

Press play listen, or read the transcript to learn more about the differences between modern and ancient bison bones.

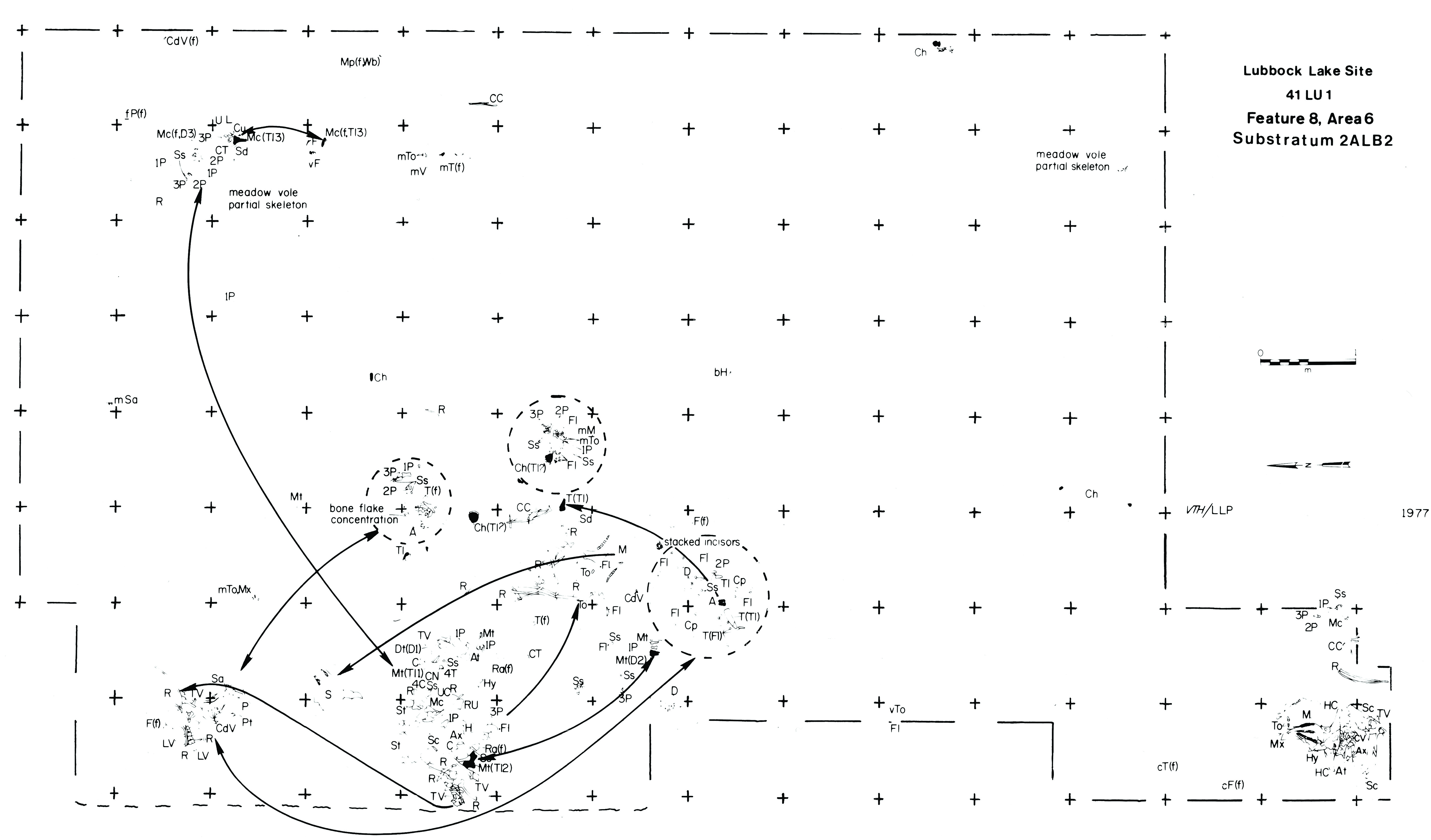

Folsom at the Lubbock Lake Landmark

The Landmark got its start by the discovery in 1936 of a single Folsom projectile point found on a back dirt pile from dredging work to revitalize the Landmark’s springs.

The discovery of this Folsom projectile point began an odyssey of research that continues on today.

Excavation at Lubbock Lake revealed a series of Folsom-age bison kills around marshy ponds in the draw. Small cow-calf herds likely were killed in the late fall into winter. Hunter-gatherers used projectile points and cutting tools made from Edwards Formation and Alibates cherts to kill and butcher the animals.

Carcasses were stripped of all meat and certain bones were broken for making tools to be used immediately for butchering the animal (known as bone expediency tools).

Folsom Bone Expediency Tool

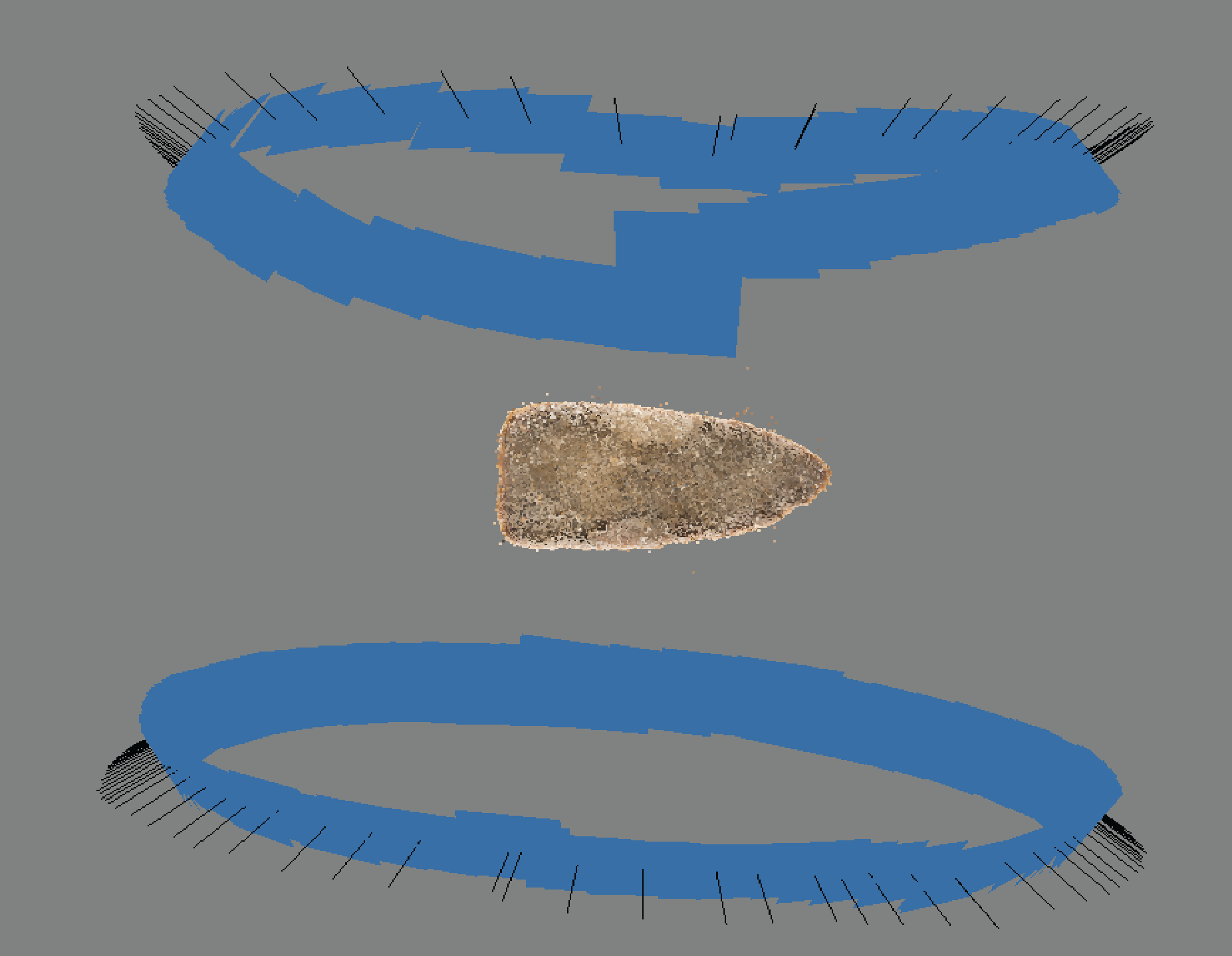

Press play on the model to explore a Folsom Bone Expediency Tool in 3D

You can drag and rotate the Folsom Expediency Bone Tool to see it at all angles. At the physical exhibit, models are printed so that visitors can handle them.

Skip 3D modelLocal sources of stone also were used in making expediency butchering tools

Folsom Bone Expediency Tool

Bone expediency tool from a Folsom kill/butchering locale at Lubbock Lake

Expediency tool: a quick tool manufactured for use on-site.

Press play to listen, or read the transcript to learn more about bone expediency tools.

Folsom Projectile Point

Folsom projectile point made from Edwards Formation chert from a kill/butchering locale at Lubbock Lake

Press play to listen, or read the transcript to learn more about Folsom projectile points.

3D Technology

Timelapse video of a 3D printer printing a Folsom Point (silent)

3D models are created in a variety of ways. The 3D models here were produced using photogrammetry.

Photogrammetry is the science of using overlapping photographs to measure distance between objects.

The photographs then are stitched together automatically in a computer software program to create a 3D rendering or a 3D model of the object(s). During the model creation, a point cloud, a mesh, and finally a texture layer are produced.

- point cloud- a series of points with 3D attributes (x,y,z) obtained from overlapping images.

- mesh- a surface of the object calculated from the point cloud

- texture- imagery from the photographs drapped onto the mesh layer to create a photorealistic model.

Step 3. Create surface mesh from the point cloud. The software produces a surface by creating millions of intersecting polygon facies that encompasses the point cloud. Over 1,100,000 million facies were created in making the Folsom ultra-thin biface. At this stage, the ultra-thin biface is ready to print.

Once a 3D model is created, it can be evaluated, edited, and exported in a 3D file format for 3D printing. 3D printing, also known as additive manufacturing, is the process of producing a physical object from a 3D model by laying down successive layers of material.

3D printing allows interaction with objects in unparalleled ways and it is a technology that is relevant in many professional fields. Architects and engineers utilize 3D printing to create prototypes while children use 3D printing to create new toys, especially legos. 3D modeling and 3D printing allow museums to share cultural and natural heritage in new and innovative ways.

3D technologies are an integral part of both research and sharing results of this work with the public. High quality 3D digital models gives researchers the ability to zoom in and view the objects at high resolution for study.

These technologies also create an opportunity to share research with a wider audience and in more interactive ways. For example, the ultrathin biface is an important example of Folsom technology and by 3D printing it, visitors are able to touch the flake scars and thin edge to get a better sense of how this archaeological object was formed and used. 3D digital models also allow for the seamless application of braille for increased accessibility to the blind community.

The Landmark research team currently is using 3D models to examine in greater detail how Folsom flintknappers prepared Folsom projectile points through fluting. The 3D models allow Landmark researchers to take different types of measurements that include area and volume not possible with traditional types of analysis.

Resources

Visit the Exhibit

The Lubbock Lake Landmark is free to the public.

Engaging Hunter Gatherers (10,800-10,200) with 3D Technology was on display until October 31st, 2017.

For Visitors

Read about the exhibit in the news: Please Touch the Exhibit

Display case at the exhibit

Directions

The Lubbock Lake Landmark is located at:

2401 Landmark Drive

Lubbock, Texas

Hours

Tuesday through Saturday: 9 a.m. - 5 p.m.

Sundays: 1 p.m. - 5 p.m.

Closed Mondays

Contact Us

806 742-1116

lubbock.lake@ttu.edu