Brainwave

By: Heidi Toth

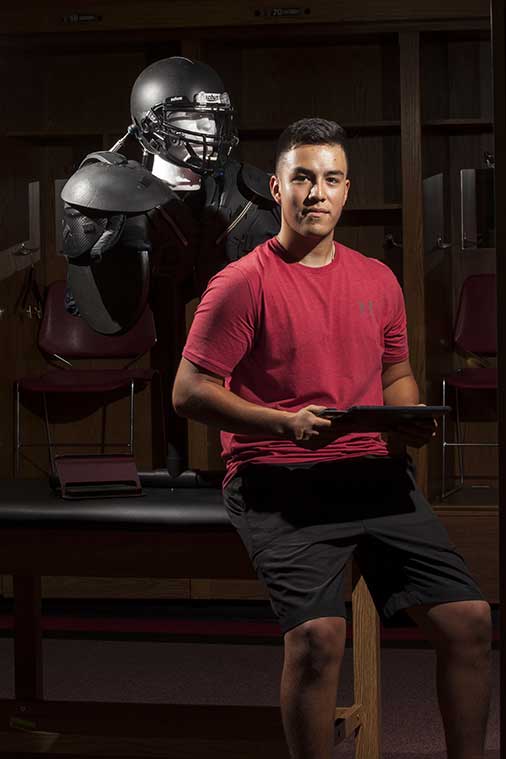

How a Texas Tech student designed a concussion warning system for football players.

Woodpeckers. Long-horned rams. American football players.

They all have one major thing in common: frequent, repeated blows to the head.

Humans, however, seem to have a weakness not shared by the animals: they are more likely to suffer brain injuries from these impacts.

“Why is it that none of these animals actually sustain any brain injury?” asked Alberto Garcia, an incoming sophomore at Texas Tech University.

He came across this phenomenon as a sophomore at Olton High School while working on his science fair project, which aimed to reduce concussions among football players. In his research he learned that, despite repeated impact to the head from trees or charging rams, studies found little evidence of brain damage in either woodpeckers or rams.

As he kept reading, Garcia learned both of these animals have natural stabilizers around their necks, which keeps their heads from whipping front and back on impact. Humans, without such stabilizers, suffered repeated impacts from this whiplash motion after the initial impact, which contributed to brain damage.

This research led him to create a helmet-and-shoulder pads system with a microcontroller that he programmed to stabilize the head immediately after impact, eventually catching the attention of the U.S. military and national engineering organizations when he presented it at an international science and engineering fair.

Keep in mind: All of this was before he graduated from high school. Even the mentor who started Garcia on the path had no idea what was coming.

“When he showed me his project I was just floored,” said Elias Perez, a science teacher at Olton and Garcia's mentor. “I've never seen anything that sophisticated come from a high school student.”

Becoming an innovator

Garcia grew up wanting to be a surgeon.

“That quickly changed at the age of 10 when I started taking apart my parents' VCR,” he said. “The DVD player was after that. Every TV we would throw away, I would take it apart, take out all the components and see how it functioned. If I couldn't fix it, I would just admire it.”

His parents, however, knew medical school wasn't in their son's future.

“Since he was small I could see that he liked to take apart the VCRs and the TVs and the radios, and I knew he was going to end up going for something that had to do with electrical engineering or something in that field,” his mother, Esperanza, said. “I just saw him as a little tornado that would tear things apart.

“He would take them apart, and in the end he wouldn't fix anything but he would still have fun.”

Even with that love of electronics, Garcia didn't spend much time inside. In high school he played all the sports he could and was proud to call himself an athlete. He wasn't on the science and engineering team when Perez suggested he enter the science fair. Garcia thought about it, then came up with one idea: harnessing energy from magnetic fields.

Or, Perez suggested, he could look into a topic a little closer to home. They talked about football and the concussion Garcia suffered just a couple of weeks prior. He decided to look at ways to reduce concussions among football players and started with the basic research.

As he read about concussions, Garcia learned two types of motion, linear and rotational, contribute to concussions. Linear acceleration force comes from the direct impact. The rotational acceleration motion is the whiplash motion of the neck and rotation of the head and neck, which caused the brain to continue bouncing off the skull after the initial impact.

“Rotational acceleration forces were more of a key aspect in this case,” Garcia said. “They played a larger role in concussions than the linear acceleration forces.”

Armed with the knowledge of this complicating factor, he looked at what a concussion-reducing helmet would need to do. First, it needed to deflect as much of the initial impact away from the head as possible. Second, it needed to reduce that whiplash motion. Third, it needed to be small and agile enough that football players could still play football while wearing it. If it was too bulky or stiff to allow movement, it would never make it onto the football field.

This is a tough problem for experienced engineers; for a 16-year-old without any computer programming experience and not much in the way of funding or free time it seemed almost insurmountable. But Garcia plowed ahead, eventually creating a prototype that is a combination of detachable helmet and shoulder pads with stabilizers around the neck. The stabilizers are controlled by a microcontroller made by Arduino and are attached to sensors in the helmet.

When the person suffers a hit above a certain threshold, the microprocessor activates the stabilizers, which locks the helmet into place. It doesn't stop the impact of the initial hit, but it keeps the head from rattling around inside the helmet after the hit.

“If you reduce the whiplash motion of the neck, then you can reduce the odds of receiving a spinal cord or neck injury because all that energy is dispersed into the stabilizers,” Garcia said.

The system weighs five pounds, so it's not unduly heavy. The sensors also can measure the amount of force with which athletes are hit and, using a radio, can transmit that data to trainers on the sideline. Knowing that could help health care professionals diagnose concussions more accurately, he said.

At the time of his first science fair, though, all of this was in his head. Garcia hadn't built any of it by the science fair that year. He presented his hypothesis, research and theory to the judges with the prototype noticeably absent.

The theory was good enough for a silver at the regional science fair. That qualified him for the state science fair, but not for the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair, the competition he had his eye on. The disappointment didn't end there; he came home with nothing from the state science fair as well. No awards, anyway.

“I think that was the driving force,” Perez said. “He said, ‘You know what? I can win.' When he never heard his name called at the state competition, at that point forward I knew he was going to be able to do great things.”

Returning to the science fair

At the end of that school year Garcia's family moved to Shallowater, which didn't have a science and research design team. It wasn't until his senior year that Leslie Griffis, his physics teacher, told him the school was willing to pay for his entrance into the regional fair. He still wouldn't have a team, but he could enter. Since he needed to do a senior project, he picked up his concussion-reducing device where he'd left off two years earlier.

Garcia worked on his project in class and stayed up late. He rummaged through his garage and surfed Amazon looking for parts that would fit into the helmet-shoulder pad combo, including part of his father's lawnmower. He went to junkyards and bought used parts. He dropped football and spent all of his free time, and much of the time he should have been sleeping, working on his invention.

“There was literally one night I stayed up ‘til three in the morning and I just yelled out ‘yes!' and I fell back into my chair in the kitchen,” Garcia said. “My mom came into the kitchen and said, ‘What's wrong with you?' I said, ‘I finally figured it out.' It was that breakthrough moment when everything was working smoothly and perfectly and I was ready for the competition.”

The arduous part of the process was programming the Arduino, an open-source microcontroller that he learned to program through trial and error, looking up code online and combing through each line looking for mistakes. He burned through three of them by the end of his senior year, at which point he still hadn't taken a computer programming class.

“I didn't learn until I actually got to physically hold one,” Garcia said. “I had to read through the instruction booklet. It wasn't an easy journey from not knowing anything to actually programming it.”

The day of the regional science fair arrived, and Garcia nervously waited at the United Supermarkets Arena on the Texas Tech campus. He needed to win gold to qualify for the Intel fair.

“They called out bronze, they called out silver,” he said. “I thought, ‘well, there's no way I can't get this.' I was really hoping I got the gold medal, but really worried that I hadn't gotten bronze or silver, which at that point I may have been content with.”

Then he heard his name announced as the gold medal winner.

“I was literally on the verge of tears walking up there because every night I was working on the project, and after getting frustrated or bored I would watch past Intel winners get announced and see them go up there, the scholarships and all the opportunities they got. It was just very exciting, and I thought, ‘well, I want to get there.'”

He also attracted someone else's attention that day. Michael San Francisco, dean of the Honors College at Texas Tech, was a judge at the science fair. He chatted with Garcia and suggested he consult with local engineers for ideas on where to take his system.

“He had this passion for his research,” San Francisco said. “The fact that he could take his concept and put all the parts together – the mechanical parts, the electrical components and then also make it into an ergonomically usable device – all of that takes some forethought. For someone to do that as a sophomore or junior in high school is very commendable.”

At the international science fair

The Intel International Science and Engineering Fair is a little bit like the Olympics for teenage innovators, right down to exchanging pins. More than 1,700 students representing more than 70 countries attended the fair. He filled a Pittsburgh Pirates towel with pins from dozens of students.

That was day one. The next four days were “down to business,” Garcia said.

“Just walking into the room you could feel how competitive it was,” he said.

On his first day he talked to 10 judges, explaining each time about his research into whiplash motion, the hours he spent reprogramming the microcontroller and the number of times he tried the helmet and shoulder pads on, then made tweaks to the design. It wasn't quite done and the judges had some critiques, but Garcia got the feeling they liked it.

The next day was media day. Garcia stood by his project watching reporters move from table to table, asking about the projects that likely would win. He got increasingly worried as the day went on and no reporters came to his table.

“I saw them going around me to interview other students,” he said. “I thought it wasn't my moment, but they finally came around to me 20 minutes before media day was over. I had four to five stations lined up back to back.”

Day three was a ceremony for special awards and scholarships. Garcia received scholarships from the Society of Experimental Mechanics and the Office of Naval Research. The final day in Pittsburgh was the official award ceremony. After what seemed like a terminal wait, his category came up. He was praying – praying to hear his name called, praying he was in first place.

“I'm looking for first, and they call my name – third place,” Garcia said. “I sit there for a minute and think about everything. … At that time I didn't keep in mind the amazing opportunity that I had to go up there and get the award. I was sad about getting third, but afterward I realized I was third in the entire world.”

He called his parents and Perez to tell them the news. Esperanza cried, then called of their family to tell them her son won this award and was on the news. His father, Jose, told his oldest son how proud he was of him, then told Garcia's younger brother, “Your brother is No. 1, mijo.”

“He said, ‘I know my brother is No. 1, so I'll be better than him,'” Jose remembered with a laugh.

Perez also wasn't disappointed in Garcia's third-place finish. He saw this as the first measure of success for his protégé, and he expects even more.

“That's the ultimate goal, to find something you're passionate about and then find success in that,” he said.

Texas Tech and beyond

Garcia is a West Texan, but for a while he wasn't keen on sticking around. His father said when Garcia was a junior and looking into colleges, he wanted to get far away from here. Jose worried about him being too far away to help, but he didn't want to discourage his son because he was afraid he'd lose interest in college altogether. He and Esperanza didn't go to college, and they wanted their oldest son to be the first.

As the time to decide drew nearer, however, Garcia was drawn to Texas Tech. It felt like home, he said; Garcia came to the campus for years as part of Upward Bound. He'd also been on campus for the science fairs and made connections, including the continued relationship with San Francisco, who invited Garcia to his office one day to visit with Changzhi Li, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering.

“My impressions of Berto are that he is a very smart student, and it was a pleasure to talk to him,” Li said. “Berto brought his design to Dr. San Francisco's office, explained to us the design concept and the mechanism of protecting players. We gave him some suggestions regarding improving the presentation. He listened carefully.”

San Francisco also got some scholarship money for Garcia, which made coming to Texas Tech an easier decision. Both he and his parents said it was a blessing for all of them.

“It would have been difficult for us to help him if he would have gone farther away from home, and it would have been difficult for him to help us as well,” Esperanza said. “As much as he needs help from us, we also need help from him at times.”

“Thank God he decided to stay here at Texas Tech,” his father added.

Garcia continues to work on his system, including doing market research to determine its greatest potential. Garcia used the award money from the science and engineering fair to hire a lawyer and register a provisional patent for the smart system; he has a year to decide whether to get a patent.

The Intel fair also gave him ideas on other applications for the system; representatives from the Air Force and Navy thought it had potential for fighter pilots, who are frequently jerked around in their planes, or soldiers on the ground, and an engineer from the automotive industry suggested a use among NASCAR drivers.

Garcia worked with Lisa McDonald with the Texas Tech Accelerator to determine what he wanted to do with his technology. On one hand, he wants to dive into all these potential uses and work with the experts needed for his system to meet its potential, which would mean starting a business and championing his idea. But he's also thought about licensing it to another company, letting them handle the testing, research and development, while he focuses on his next great idea.

He's also looked at related ideas, including a helmet with an accelerometer in it to measure force, which was his final project for his introduction to computer engineering class.

“I just hope it's a never-ending journey, that I'm able to have a good impact on people's lives,” he said.

His biggest cheerleaders, who weren't sure what he was doing when he came home with a microprocessor, anticipate he will.

“I know how hard he's worked on this project, and I believe all these hours of work and frustration will pay off in the end with the help of God,” Esperanza said. “Hopefully his invention is out there someday saving lives and reducing concussions.”

Discoveries

-

Address

Texas Tech University, 2500 Broadway, Box 41075 Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.3905 -

Email

vpr.communications@ttu.edu