COYOTE

Canis latrans Say 1823

Order Carnivora : Family Canidae

DESCRIPTION. A medium-sized, slender, doglike carnivore, similar in appearance to the red wolf but usually smaller, more slender, with smaller feet, narrower muzzle, and relatively longer tail; colors usually paler, less rufous, rarely blackish; differs from gray wolves (Canis lupus) in much smaller size, smaller feet and skull; ears more pointed; upperparts grizzled buffy and grayish overlaid with black; muzzle, ears, and outer sides of legs yellowish buff; tail with black tip and with upperpart colored like back. Dental formula: I 3/3, C 1/1, Pm 4/4, M usually 2/2, occasionally 3/3, 3/2, or 2/3 × 2 = 40, 42, or 44. Averages for external measurements: total length, 1.2 m; tail, 394 mm; hind foot, 179 mm. Weight, 14–20 kg.

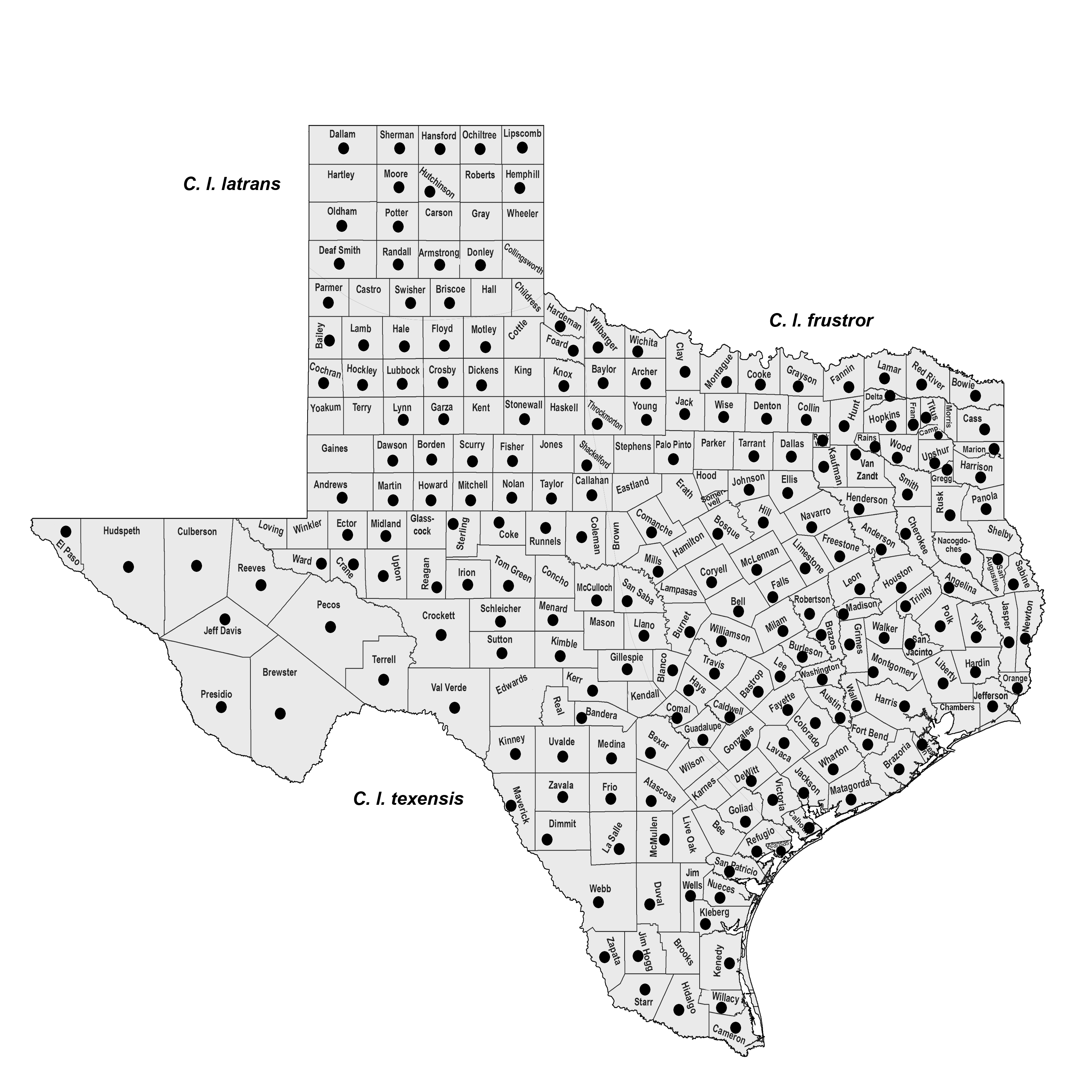

DISTRIBUTION. Statewide.

SUBSPECIES. Canis l. latrans in the Panhandle, C. l. texensis in the western half of the state south of the Panhandle, and C. l. frustror in the eastern half of the state.

HABITS. Coyotes eat a variety of food items, and this versatility has led to their successful invasion of much of North America, including urban areas. Considerable seasonal variation in diets is evident, with carrion of large animals such as deer, feral pigs, and cattle being important in winter and rodents, rabbits, birds, and fruits increasing in significance during spring, summer, and fall. The stomach contents of 168 coyotes collected in Arkansas contained the following items (listed as percent occurrence): poultry, 34; persimmons, 23; insects, 11; rodents, 9; songbirds, 8; cattle, 7; rabbits, 7; deer, 5; woodchucks, 4; goats, 4; and watermelons, 4.

Coyotes are extremely social animals forming family units or packs. A pair typically forms in midwinter when a female comes into heat (estrous) and attracts a sexually active male. Breeding generally occurs between January and March with the female and her mate copulating several times during the last few days of her estrous period.

Following a successful breeding, the pair establishes a territory and prepares a den, usually excavated along brush-covered slopes, steep banks, thickets, hollow logs, or rock ledges. Coyote pairs maintain a strong social bond throughout pregnancy and pup-rearing stages. They hunt and sleep together, but during late pregnancy and early periods of lactation, the male frequently hunts alone and brings food to the female and pups.

The percentage of females that successfully breed during a given year may vary with local conditions and resources. The coyote pair produces a single litter per year (monestrous) with normal litter size ranging from 2 to 12, averaging about 6. The gestation period is approximately 63 days.

Newborn pups weigh 200–250 g, depending on litter size. They are born blind and helpless. Pups are nourished exclusively on milk for the first 10 days. Their eyes open on the 10th day, at which time they become more active and begin to move around the den entrance. Their incisors appear on the 12th day and the canines at the 16th day. They can walk by 20 days and can run by 6 weeks of age. At 12–15 days of age, adults start to supplement the pups' diet with regurgitated foods. Pups begin to eat solid food, such as mice and small birds, at 4–6 weeks when their "milk teeth" are functional. Lactation is progressively reduced after 2 months. Pups grow and mature at a rapid rate, reaching adult size by early fall. Considerable variation in size exists, with individuals in the Panhandle and northern regions of Texas being considerably larger than those in the more southern parts of the state.

The months of May, June, and July serve as the training period for pups. Pups learn to accept regurgitated food from their parents, play fight, catch insects, and hunt and kill small prey. The den is abandoned by late June or early July as the family begins to traverse larger areas in search of food. November and December are the primary months when the young disperse.

Coyotes may be active throughout the day but tend to be more active during the early morning and evenings or at night. Their movements include travel within a territory or home range, dispersal from the den, and long migrations. The home-range size of coyotes varies geographically, seasonally, and individually within populations, generally ranging from 10 to 20 km2 (4–8 mi.2).

Nonfamily coyotes include bachelor males, nonreproductive females, and near-mature young. They may live alone or form a loose, temporary association for social contact or hunting so that they can survive until the next breeding season. Two to six animals may band together with one individual being dominant.

Few coyotes live more than 6–8 years in the wild, although they may live considerably longer in captivity. Fatalities are due mainly to predation, parasites and disease, and human activity. Mortality is particularly high among the young. Pups are vulnerable to hawks, owls, eagles, mountain lions, and even other coyotes. Hunting, trapping, and automobiles account for most of the adult fatalities. Although dogs and coyotes are generally adversaries, they may be more compatible during the breeding season and even occasionally interbreed. Coyote–dog hybrids, called "coy-dogs," usually retain coyote appearance and behavioral patterns. The breeding season of hybrids is random, and most are unable to breed back into the coyote population. Hybridization among coyotes, wolves, and dogs is problematic from a conservation standpoint, as it reduces "pure" genetic stocks of each respective species.

Coyotes communicate by vocalization and scent marking. They are among the most vocal of all North American wild mammals and they emit three distinct calls (squeaks or yips, howls, and distress). The unmistakable calls of coyotes serve primarily for announcing the position and hunting success of the caller. These coyote "songs" are more frequent during the breeding season and early summer than at other times of the year. Coyotes often urinate or defecate on scent posts, which may be a post, stump, bush, rock, dried cow dung, or a bare spot. A visiting animal may go many meters upwind to investigate a scent post and leave his mark. Whether these actions represent a territorial claim, a warning device to other coyotes, or simply indicate the presence of an individual is not known.

In recent years, the coyote has declined significantly in economic importance as a fur-bearing animal in the state. In 2001–2002, trappers reported capturing 16,604 coyotes. This ranked the coyote as second, behind the raccoon, in terms of economic importance. The trapper report survey was abandoned in 2003, making it difficult to determine the number of coyotes trapped in Texas; however, fur buyers reported purchasing substantially fewer pelts in recent years.

POPULATION STATUS. Common. Coyotes are common throughout all of Texas, and populations are expanding their ranges throughout much of North America. Coyotes have thrived in the last 150 years. Two centuries ago, they led a very different life, hunting rabbits, mice, and insects in the grasslands of the Great Plains. Weighing only 10–12 kg on average, they could not compete in the forests with the much larger gray wolf (Canis lupus), which are quick to dispatch coyotes that try to scavenge their kills. Their big break came when settlers pushed west, wiping out the resident wolves. Coyotes could thrive because they breed more quickly than wolves and have a more varied diet. Since then, their menu has grown and so has their range. In the past two centuries, coyotes have taken over part of the wolf's former ecological niche by preying on deer and even on caribou.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the coyote as a species of least concern and one that is increasing its range. Coyotes do not appear on the federal or state lists of concerned species.

REMARKS. Coyotes have adapted well to humans and to urban environments. Intensive efforts to control their numbers fail more often than not. In fact, removal of resident coyotes often leads to the immigration of dispersing juveniles that are more likely to predate livestock or crops. This is a species that will likely continue to flourish as humans exert a greater influence over the natural landscape.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu