AMERICAN BLACK BEAR

Ursus americanus Pallas 1790

Order Carnivora : Family Ursidae

DESCRIPTION. A medium-sized bear, black or brown in color; snout brownish in the black color phase; front claws slightly longer than the hind claws, curved, adapted for climbing; profile of face nearly straight, not concave as in the grizzly; fur long and rather coarse. Dental formula: I 3/3, C 1/1, Pm 4/4, M 2/3 × 2 = 42. Averages of external measurements: total length, 1.5 m; tail, 125 mm; hind foot, 175 mm; height at shoulder about 625 mm. Weight, 100–150 kg; occasionally as much as 225 kg.

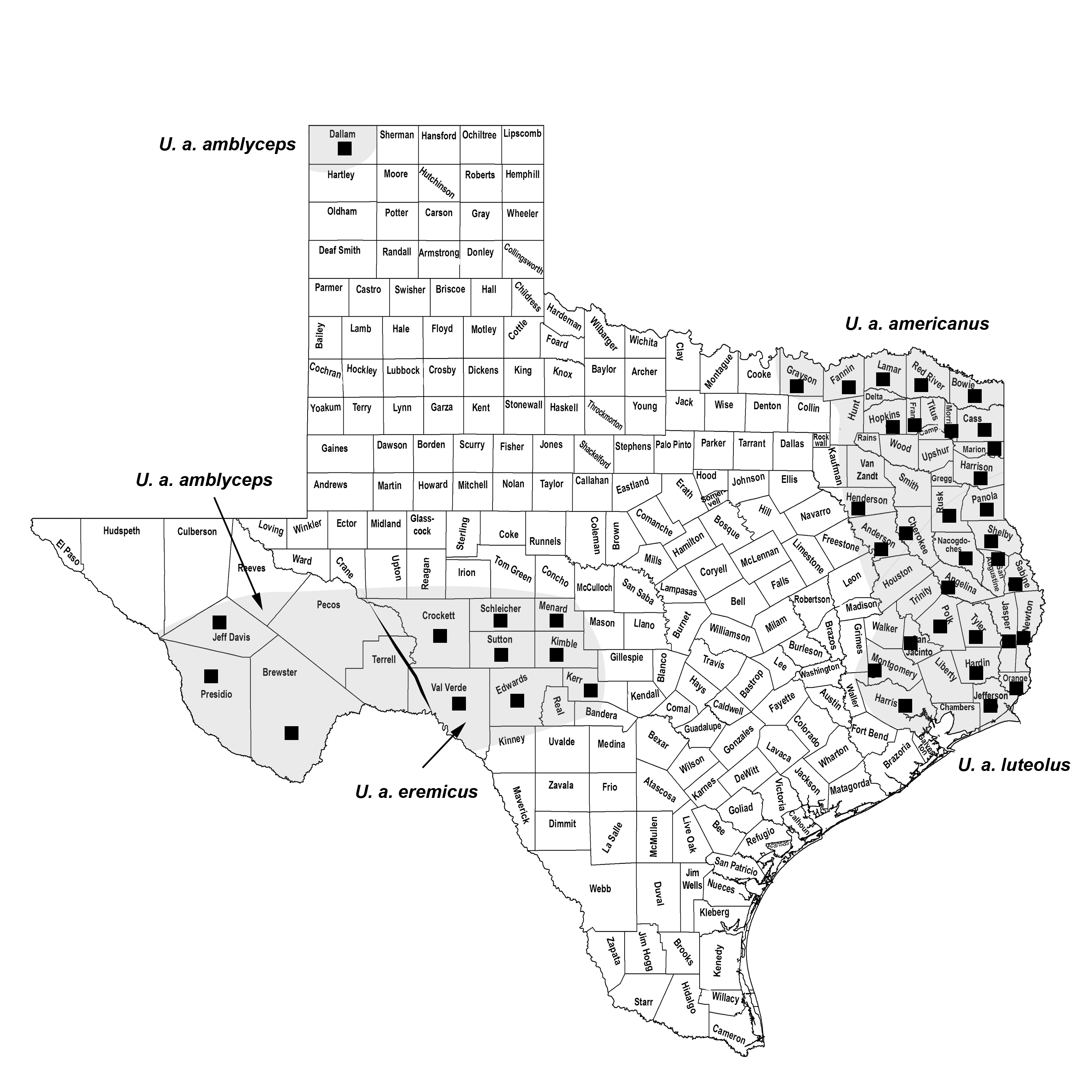

DISTRIBUTION. Formerly widespread throughout the state. From the 1960s to the early 2000s, American black bears were restricted to remnant populations in mountainous areas of the Trans-Pecos region (Brewster, Presidio, and Jeff Davis counties); however, black bear populations have regained a foothold in East Texas and in the western portions of the Edwards Plateau. This resurgence appears to have been a product of immigrant bears from Oklahoma, Louisiana, the Trans-Pecos region, and Mexico. In addition, recent reports of sightings in the Panhandle (Dallam County) indicate possible immigrants from New Mexico or Colorado. Given the number of sows with cubs being reported, it appears that many of these sightings include resident and not just transient bears. Although we normally require a voucher specimen to verify a distributional record, given that black bears are protected and that they are not likely to be confused with any other species, we have chosen to indicate recently confirmed sightings (based on TPWD reports) on the black bear distribution map.

SUBSPECIES. Ursus a. amblyceps in the Trans-Pecos area and northward along the New Mexican border, U. a. americanus in the north-central part of the state, U. a. luteolus in the east adjacent to Louisiana, and U. a. eremicus in the western Hill Country.

HABITS. American black bears generally inhabit woodland and forested areas; however, in the Trans-Pecos region they may occur in more open grassland areas. They are expert climbers and the young often seek refuge in trees; however, adult black bears are more at home on the ground than in trees. Ordinarily, bears are shy and elusive. They appear to use definite travel ways as they move from feeding to bedding areas.

In the colder parts of their range, black bears hole up in a den, a windfall, at the base of a tree, under a rock ledge, or other suitable site and are inactive for a part of the winter. They do not exhibit the characteristics of true hibernation; their temperature does not drop markedly and the heartbeat and respiratory rate are only moderately reduced. They may awaken and become active during a warm spell in midwinter and return to the den to sleep when the temperature drops.

Food preference is extremely variable and is reflected in the dentition. The molar teeth are modified for grinding and crushing and are less specialized than those of a strict carnivore. They are known to feed upon insect larvae (grubs), bees, carpenter ants, and other insects, several types of berries, wild cherry, poison oak, apples, pine nuts, acorns, clover, grass, roots, fish, carrion, and human garbage. Occasionally bears kill livestock, feral pigs, and young deer.

The breeding season is in June or July; however, implantation is delayed until November. The gestation period is 210–217 days and one to four young (usually two) are born in January or February, while the mother is "hibernating." At birth the young (cubs) are blind, covered with a sparse growth of fine hair, and almost helpless. They weigh <500 g and are about 15 cm long. They grow slowly; their eyes open at about 6 weeks. By the time the mother leaves the winter den the cubs have developed sufficiently to follow. Cubs remain with the female until the fall of their second year when they disperse. By that time, the female is preparing for her next family. Normally, old females mate every other year, and young females do not mate until >2 years of age.

Bears have few predators other than humans. Their chief economic value is as a game animal in states that allow hunting. Their pelts have little value on the fur market, but they are prized as trophies. In recent years, bear gall-bladders have become valuable on the black market, which has led to an increase in poaching.

POPULATION STATUS. Rare. Until recently, the American black bear was considered to be extinct in Texas, although bears occasionally were sighted in the Chisos Mountains of Big Bend National Park. The last decade of the twentieth century, however, witnessed a natural restoration of black bear populations in Texas as a result of a coalescence of biogeographic, ecological, and sociological factors. The presence of bears in adjacent but geographically isolated mountain ranges in northern Mexico facilitated the colonization of populations. In Coahuila, Mexico, just across the border from Texas, black bear populations have increased from previously endangered levels to one of the highest densities in North America because of landowner initiatives and encouragement from the Mexican government. Bear populations are now spilling over into the Big Bend region and other areas of west and southwest Texas. This case is worth noting because natural recolonization of historical range by large carnivores is uncommon in today's world of habitat fragmentation, disturbance, and destruction. American black bears have been sighted in 31 counties in East Texas (Big Thicket area), primarily the result of individuals that have wandered into the state from release sites in Louisiana. In addition, there have been several recent sightings throughout the Hill Country region. In 2012, a black bear was sighted north of Dalhart. This individual presumably was a wanderer from the Raton, New Mexico, area.

These recent sightings suggest that breeding populations now exist in the Chisos, Guadalupe, Davis, and Glass Mountains, the limestone canyon areas around Comstock in Val Verde County, as well as in the Big Thicket area. These data may signal the return of permanent black bear populations to Texas.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the American black bear as a species of least concern. The USFWS lists the Louisiana subspecies (U. a. luteolus) as threatened and designates the entire species as "threatened, by similarity of appearance to a threatened taxon." The TPWD lists the black bear as threatened in Texas. Although this species is increasing in numbers, monitoring efforts should be continued.

REMARKS. In 2014, Fred Stangl (Midwestern State University) and RDB completed a study of a recent black bear fossil (~100 years old) from near Junction, Texas. This fossil, clearly a black bear, approached grizzly bear size in its cranium. Comparison with other fossil black bears from Texas and Oklahoma demonstrated that black bears from the late 1800s reached much larger sizes than those of today. The authors hypothesized that prior to European settlement, bears lived longer and thus were able to obtain larger sizes.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu