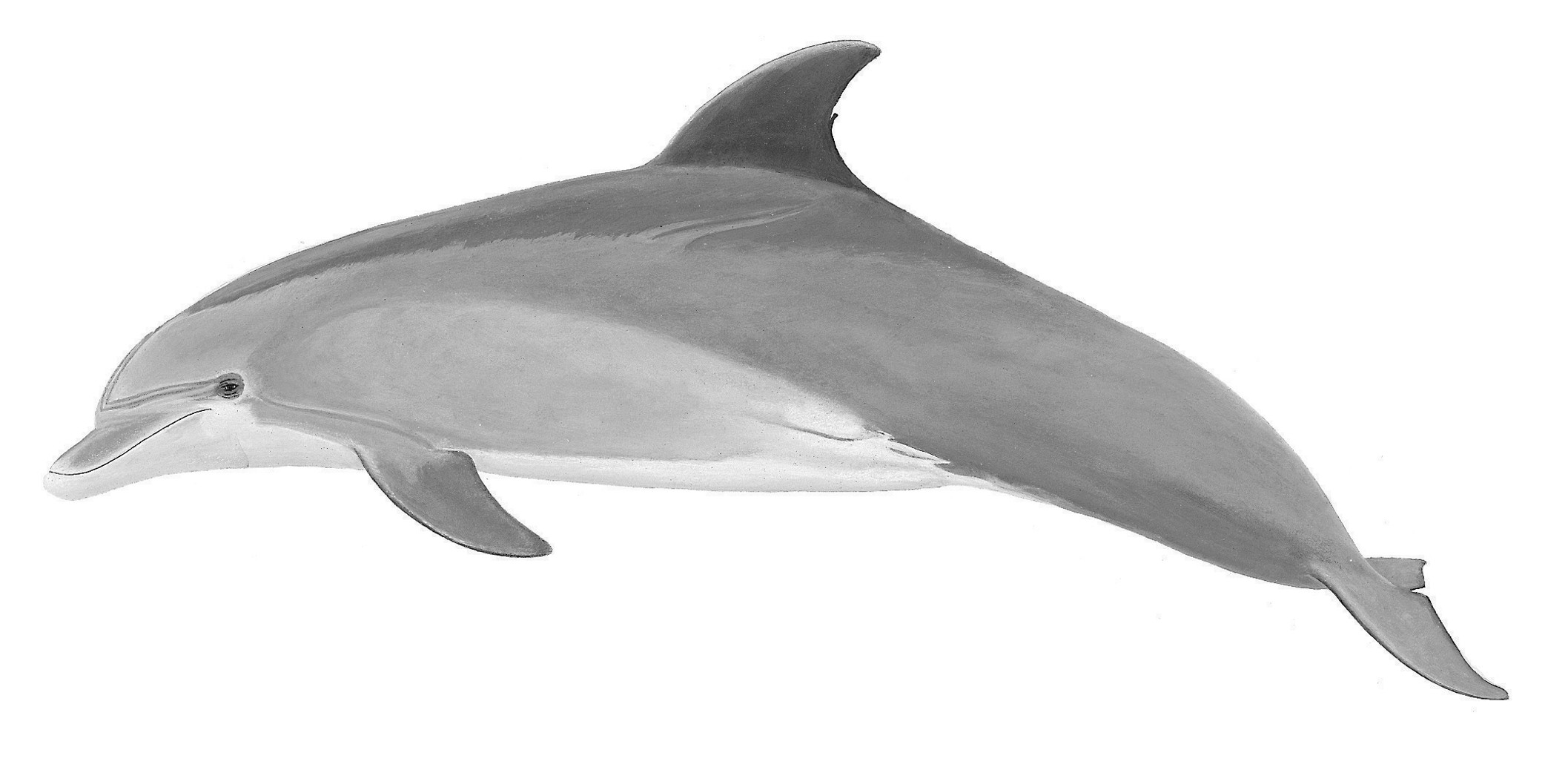

COMMON BOTTLENOSE DOLPHIN

Tursiops truncatus (Montague 1821)

Order Cetacea : Family Delphinidae

DESCRIPTION. A rather stout, short-beaked (seldom >75 mm long) dolphin with sloping forehead and projecting lower jaw; dorsal fin high, falcate, and situated about midway from snout to flukes; pectoral fin broad at base, obtusely rounded at tip; upperparts plumbeous gray, more or less tinged with purplish, becoming black soon after death; sides pale gray, belly white. Teeth in each side of upper jaw number 20–26 and in each side of lower jaw 18–24; teeth large, nearly round in cross section in adults, and conical, height above jawbone 12–17 mm, diameter 5–9 mm. Total length of adults may reach 3.5 m.

A subadult male measured total length, 2.9 m; length of mouth, 319 mm; tip of snout to dorsal fin, 1,275 mm; length of pectoral fin, 395 mm; vertical height of dorsal fin, 229 mm; and breadth of flukes, 612 mm.

DISTRIBUTION. Common bottlenose dolphins are found in tropical and temperate waters of all oceans and peripheral seas. Because of their coastal habits, prevalence in captivity, and appearances on TV and in oceanarium shows, we know more about these dolphins than any other cetacean. In the Gulf of Mexico, bottlenose dolphins are the most common and widespread coastal species. They occur primarily near shore and are especially common near passes connecting bays to the open ocean, although they are also found in lagoons, rivers, and open ocean areas. This is the most common cetacean along the Texas coast.

SUBSPECIES. The taxonomic status of T. truncatus is in question, and further research is required to determine if subspecies assignments are justified.

HABITS. Common bottlenose dolphins may be seen in groups numbering up to several hundred, but smaller social units of 2–15 are more common. Group size is affected by habitat structure and tends to increase with water depth. Group members interact closely and are highly cooperative in feeding, protective, and nursery activities. These dolphins make numerous sounds and are probably both good echolocators and highly communicative.

Common bottlenose dolphins eat a wide variety of food items, depending on what is available and abundant at a given time. In Texas waters they eat sharks and fishes, including tarpon, sailfish, speckled trout, pike, rays, mullet, and catfish. They are also known to eat anchovies, menhaden, minnows, shrimp, and eel. They eat about 18–36 kg of fish each day. Commonly observed feeding behaviors include foraging around shrimp boats, either working or not, to feed on fish attracted to the boats. The dolphins also eat bycatch dumped from working trawlers. Groups of these dolphins have been observed cooperating in prey capture, with several dolphins herding fish into tight schools that are more easily exploited. Bottlenoses also are known to chase prey into very shallow water and may lunge onto mud banks and shoals in pursuit of panicked fish.

Of 15 females captured in Texas waters, 6 that were pregnant were taken between 17 December and 19 March. On the first date, the fetus was 78 cm long and weighed 5 kg; on the last date fetuses were almost as large as some of the small calves. Nursing females were all taken between 20 April and 11 September. Those data suggest that breeding occurs in the summer and that the young are born the following March to May. At birth, the calf, usually about 1 m in length, is more than one-third as long as its mother. Females give birth to a single calf every 2–3 years. Males mature at 10–13 years of age and females at 5–12 years, when about 2.4 m in length. The family group may remain intact for nearly 1 year, as suggested by the capture on 24 February of a pregnant female and a young male approximately 1.5 m in length. The two animals were traveling together and were presumably mother and son.

Bottlenose dolphins are commonly seen in bays, estuaries, and ship channels. Two distinct forms may occur in the Gulf: inshore animals that inhabit shallow lagoons, bays, and inlets; and oceanic or offshore populations that remain in deeper waters. Interaction between the two populations is thought to be minimal. Populations of these dolphins in the southern and central portions of the Texas coast appear to increase dramatically in fall and winter. Either offshore dolphins move into nearshore waters during these seasons, or dolphins from adjacent bay systems move into the coastal sections.

POPULATION STATUS. Common; strandings and observations. More than 90% of the strandings of marine mammals in the Gulf are composed of common bottlenose dolphins, and the species regularly strands and is sighted all along the Texas coast. Although numerous in Gulf waters, exact population numbers are not known, and it is not clear whether inshore bay and nearshore dolphins constitute one population or several. The best estimate for the number of bottlenose dolphins in the northern Gulf of Mexico appears to be around 78,000 individuals with about 5,000 in bays, 18,000 in coastal waters, and 55,000 in deeper continental slope waters.

CONSERVATION STATUS. Common bottlenose dolphins are not listed as a species of concern by either the USFWS or TPWD. The IUCN considers their status as least concern because, although many threats impact local populations, the species is widespread and abundant and none of the threats seem to be resulting in major global population decline. There seems to be no indication that populations are declining along the Texas coast. All cetaceans, including bottlenose dolphins, are protected from hunting by strict laws but are affected by other human activities. In the Gulf these activities include petroleum resource development, heavy boating traffic, and the pollution of Gulf waters. However, the cumulative effects of those factors on dolphins are difficult to determine. Bottlenoses have been observed swimming through heavy oil spills and superficially show no ill effects. Bottlenoses may be able to adapt to human activities, but they probably are readily affected by pollution and would make a good indicator species signaling the overuse and excessive pollution of Gulf waters.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu