CAVE MYOTIS

Myotis velifer (J. A. Allen 1890)

Order Chiroptera : Family Vespertilionidae

DESCRIPTION. Largest of the Myotis in Texas; hind foot large, more than half as long as tibia; ear short, reaching to or slightly beyond nostril when laid forward; upperparts uniform dull sepia; underparts much paler, tips of hairs pale cream buff. Dental formula: I 2/3, C 1/1, Pm 3/3, M 3/3 × 2 = 38. Averages for external measurements: total length, 90 mm; tail, 40 mm; foot, 9 mm; forearm, 42 mm. Weight, 12–15 g.

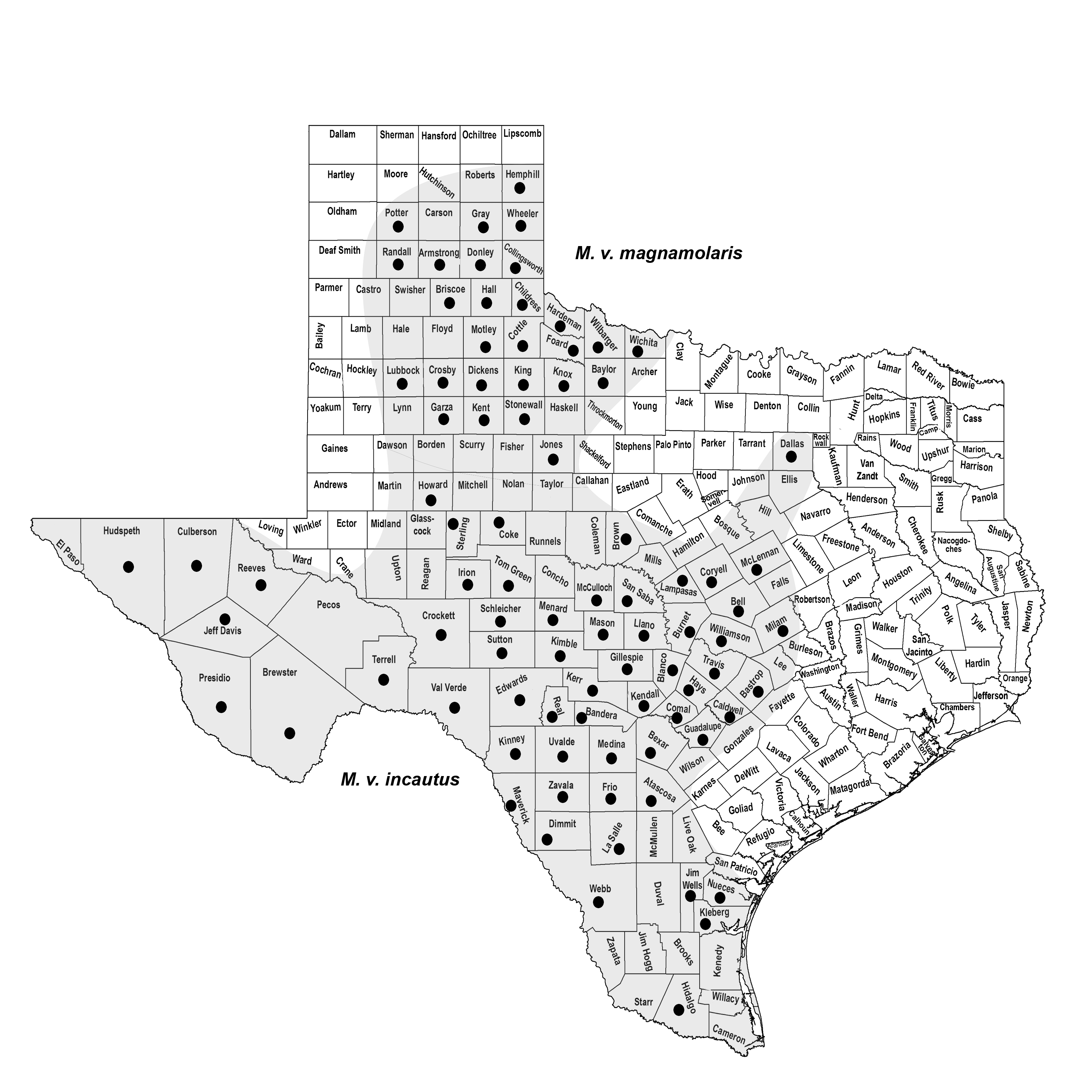

DISTRIBUTION. The cave myotis is a year-round resident of Texas, occurring over most of the Trans-Pecos, South Texas, eastern portions of the Panhandle, north-central Texas, and the Edwards Plateau. It occupies all of the major vegetative regions except for the Pineywoods. A recent Texas Department of State Health Services record from Dallas County extends the range to the east into north-central Texas.

SUBSPECIES. Myotis v. incautus in the south and M. v. magnamolaris to the northwest.

HABITS. This is a colonial, cave-dwelling bat that roosts typically in clusters numbering into the thousands. They may also roost in rock crevices, old buildings, carports, under bridges, and even in abandoned cliff swallow nests. The cave myotis is second in abundance only to Tadarida brasiliensis on the Edwards Plateau, and it hibernates in central Texas caves in winter. It also hibernates in the gypsum caves of the Panhandle where it is occasionally found with big-eared bats (Corynorhinus spp.), Brazilian free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis), big brown bats (Eptesicus fuscus), Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis), and ghost-faced bats (Mormoops megalophylla). Although those bats may roost at the same site, the different species usually segregate, with different bats inhabiting separate areas or rooms of the roosting site.

These bats appear shortly after sunset and again just before sunrise to forage. They have been observed on several occasions coming into pools of water and open tanks in the late evening to drink. Their flight is stronger and less erratic than that of other species of Myotis.

Cave myotises are opportunistic insectivores that feed on a wide variety of insects, depending on what is most available on a given night. Small moths make up the largest portion of the diet, although small beetles, weevils, and ant lions are also taken. Because of their larger size and stronger flight, the cave myotis may be able to forage farther abroad than other species of Myotis.

Data on their reproductive habits are sparse. As with many other vespertilionids, M. velifer typically mates in the fall; ovulation and fertilization are delayed until the spring. In Texas, females have been found with embryos as early as mid-April, and on the Edwards Plateau lactating females are frequently captured in May.

One young per year is born to the female. Newborn bat pups are lightly haired and pink skinned and have dark membranes and ears. Baby bats are "hung" in a nursery colony with other newborns, where they are nursed and protected by the adult females. Such nursery colonies can be quite large but generally contain between 5,000 and 10,000 bats. The young are capable of flight at about 3 weeks of age, and may be moved to a different location by the mothers if the nursery colony is disturbed.

POPULATION STATUS. Common, year-round resident. Capture records suggest that the cave myotis is abundant throughout its known distribution in Texas, especially in areas where caves are common. Disruption of roost sites and pesticides have been implicated as threats in other parts of its range, though very little is known about such problems in Texas.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN status of the cave myotis is least concern, and it does not appear on the federal or state lists of concerned species. The IUCN status is based on the species-wide distribution, apparently stable population, occurrence in a number of protected areas, and tolerance to some degree of habitat modification. Cave bats still appear to be common throughout their range in Texas, and at this time, there does not appear to be any reason to be concerned about their long-term status in the state. Obviously, this could change rather quickly and dramatically should white-nose syndrome become established and widespread in Texas caves.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu