BIG FREE-TAILED BAT

Nyctinomops macrotis (Gray 1839)

Order Chiroptera : Family Molossidae

DESCRIPTION. Similar to the Brazilian free-tailed bat, Tadarida brasiliensis, but much larger; ratio of foot to tibia about 0.53; second joint of fourth finger 2.5 mm in length; ears large and joined at their bases for a short distance over forehead; upperparts ranging from light reddish brown to rich dark brown; underparts similarly colored but paler. Dental formula: I 1/2 or 1/3, C 1/1, Pm 2/2, M 3/3 × 2 = 30 or 32. Averages for external measurements: total length, 134 mm; tail, 51 mm; foot, 9 mm; ear, 25 mm; forearm, 61 mm. Weight of nonpregnant females in June, 22 g; of fat, October-taken, nongravid females, 24–30 g.

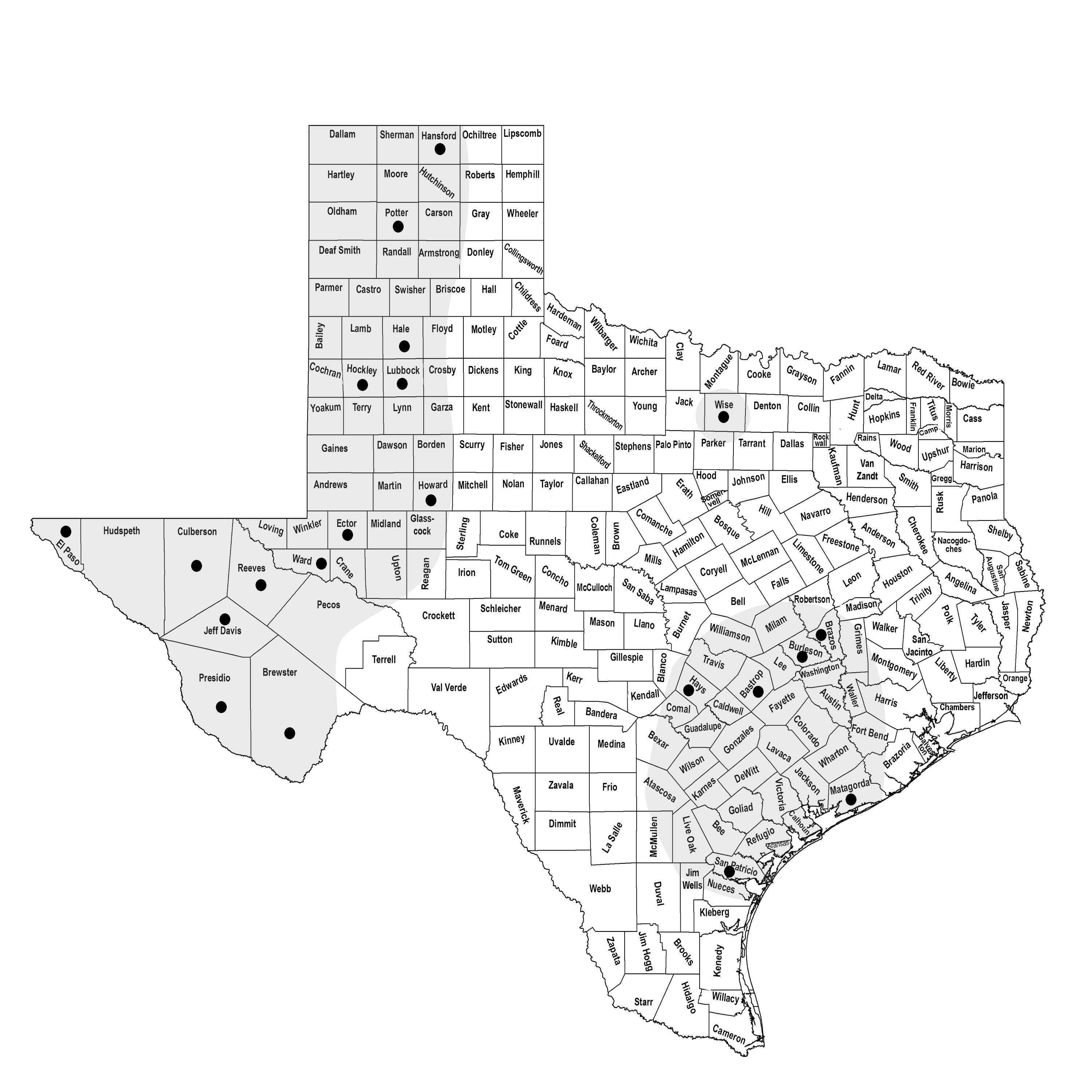

DISTRIBUTION. This bat is widely, but seemingly sparingly, distributed from Iowa and southwestern British Columbia in the north, southward through Mexico and the West Indies as far as Uruguay in South America. It is known in Texas from scattered localities in the Trans-Pecos, Panhandle, and southern portions of the state. A recent Texas Department of State Health Services specimen has been recorded from Wise County in north-central Texas.

SUBSPECIES. Monotypic species.

HABITS. This bat is rare in collections and little is known of its habits. In Texas these bats have been recorded primarily from the Trans-Pecos, where they seem to be seasonal inhabitants of rugged, rocky country in both lowland and highland habitats. With the exception of a single specimen from San Patricio County, which was found hanging on a screen door at the Welder Wildlife Refuge in December 1959, no winter records of this species have been recorded for Texas. In summer, a segregation of sexes apparently occurs, as evidenced by the small number of males taken in the Trans-Pecos.

Preferred roosting sites are crevices and cracks in high canyon walls, but these bats have also been captured in buildings. A specimen from Brazos County was obtained when it flew down a chimney and into the owner's house. The only known nursery colony of these bats in the United States was discovered in the Chisos Mountains of Brewster County in Big Bend National Park on 7 May 1937 by A. E. Borell. His attention was attracted to a horizontal crevice in a cliff near the head of Pine Canyon by the squeaking of bats. He estimated the number of adults using the site to be about 150, and all those he collected were adult females, most of which were pregnant. He revisited the colony on 19 October 1938 and collected four more specimens, all females. On 27 October 1958, some 20 years later, William B. Davis visited the colony with Richard D. Porter. Their field notes, written the next day, follow: "We hiked up Pine Canyon as far as the falls (a trickle of water over a cliff about 100 feet [30 m] high). The canyon is narrow and steep-sided and has a few large yellow pines, but most of them are dead. To the right of the falls the cliff is overhanging, and it has several more-or-less horizontal crevices paralleling the top. One of them, about 50 feet [15 m] above the talus and some 100 feet [30 m] north of the falls, contained the colony. We could clearly hear the bats chattering, much like the muted coo of doves." A considerable quantity of guano on the talus at the base of the cliff marked the place above which the bats were roosting. None of the bats voluntarily left the roost while they were there.

Borell found that the bats left the roost on 7 May at 8:20 p.m. (MST), when it was almost dark, and nearly an hour after the first American Parastrelle was observed. The bats left in small groups during a period of 15 minutes. The swish of their wings was plainly audible, and their flight was rapid. It was so dark when they emerged that he could not determine whether they flew up or down the canyon. Possibly their habit of leaving their daytime roosts so late is the reason they seldom are seen and rarely collected.

Another maternity colony is thought to be in McKittrick Canyon in Guadalupe Mountains National Park. In June 1968 and August 1970, Richard LaVal netted 14 N. macrotis at a pool 8 km (5 mi.) inside the canyon, where steep walls rise nearly 540 m (1,772 ft.) above the narrow canyon floor. In this section of the canyon, the bats were heard vocalizing from far above the floor. All individuals captured were females. Eight of the 12 taken in June contained a single large embryo each. One of the two females captured in August was lactating.

The winter habits of this bat are unknown, although they may possibly hibernate in the Trans-Pecos. Richard LaVal found that individuals kept in a refrigerator at 5°C for 24 hours entered a deep torpor, from which they emerged within 15 minutes after their removal. Another bit of evidence suggesting hibernation is that adult, October-taken females were very fat and weighed about 20% more than nonpregnant, June-taken females. Because they are strong fliers and prone to wander somewhat in fall, these bats often turn up far from their normal range during this season. Records from the Panhandle and north-central and southeastern Texas may represent juveniles dispersing from breeding populations in the Trans-Pecos.

In 1972, David Easterla and John Whitaker Jr. examined the stomach contents of 49 N. macrotis and reported that by far the most important food items found were the bodies of large moths. The only other items regularly found were the remains of crickets and longhorn grasshoppers. Other items the bats had consumed were flying ants, stinkbugs, beetles, and leafhoppers. In the stomachs that contained crickets and longhorn grasshoppers, these insects usually made up <25% of the contents, but in a few they constituted as much as 50%. One stomach contained only small flying ants, and one contained only large ants. These workers speculated that while in flight the bats captured the ground-dwelling insects (crickets, longhorn grasshoppers, and large ants) by picking them from the walls of the cliffs.

Little is known about reproduction and development of the young in this bat. Seemingly, each gravid female gives birth to a single offspring in late June to early July. Thirty-six pregnant females were captured in Big Bend National Park between 10 June and 7 July. In total, 73 lactating females have been captured over a 12-year period (1996–2008) at Big Bend National Park from 28 June to 27 September. Development is rather rapid, because by October the young of the year are nearly full grown and difficult to distinguish from adults. The females gather in nursery colonies, from which adult males are excluded, to rear their young.

POPULATION STATUS. Uncommon, year-round resident. The big free-tailed bat

is another uncommon and poorly known species whose situation bears watching. In total,

63 specimen records are known from Texas.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN status of the big free-tailed bat is least concern but with an unknown population trend. It does not appear on federal or state lists of concerned species. However, additional data, particularly about population size, would be helpful to establish a meaningful and biologically defensible position as to its status. As with the other large molossid species in Texas (the western bonneted bat, Eumops perotis), open-surface water from which to drink could be of critical importance to this species.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu