Arsenic in Tap Water

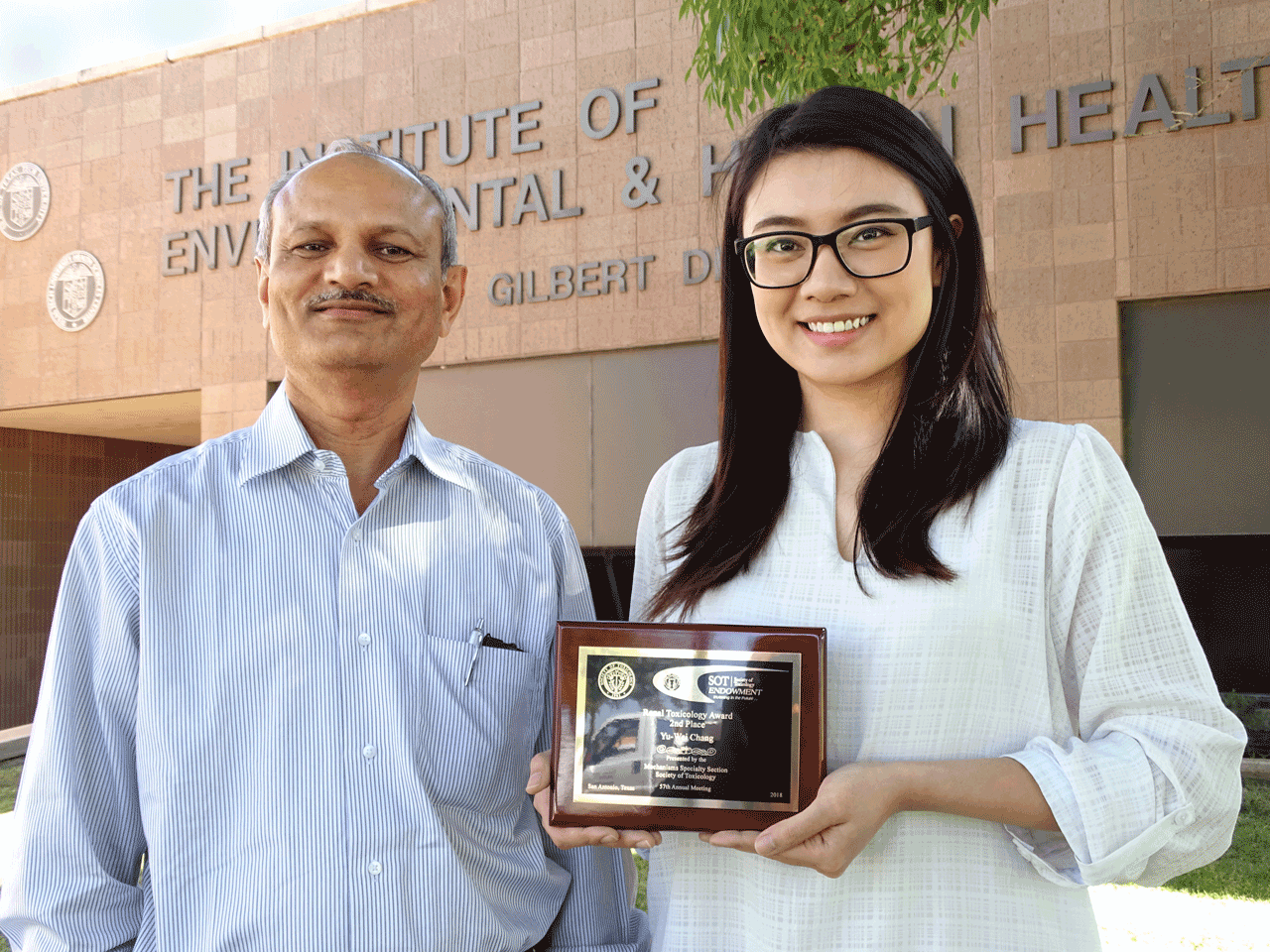

Kamaleshwar Singh, Associate Professor of Environmental Genomics and Molecular Carcinogenesis (left), and Yu-Wei Chang, doctoral candidate in the Department of Environmental Toxicology (right), with the Renal Toxicology Award Chang won for her research.

Doctoral Candidate Yu-Wei Chang Finds That Even Low Levels of Arsenic Can Cause Kidney Disease

Written by Glenys Young

Scientists have known for decades that high levels of arsenic can harm the kidneys, which filter toxins out of the blood. That's why the Environmental Protection Agency limits the allowable amount of arsenic in drinking water to only 10 parts per billion—that's about 10 drops of water out of a full swimming pool.

According to a study recently published in the Journal of Cellular Physiology, two Texas Tech University researchers have some bad news: even these low, allowable levels of arsenic may still be enough to cause kidney disease. The good news, however, is they also may have found a way to treat such kidney disease using a drug already approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—just not for this purpose.

Kamaleshwar Singh, an associate professor in The Institute of Environmental and Human Health, and doctoral candidate Yu-Wei Chang have been working on this problem for two years, exposing cells from healthy human kidneys to various concentrations of arsenic and monitoring the effects.

"Arsenic contamination is a serious, worldwide issue," Chang said. "People can easily uptake arsenic from the environment, for instance, through drinking water. Moreover, the kidney is the organ that removes the toxins and wastes from our bodies. If the kidney gets damaged, it will cause serious harmful side effects on our bodies. Hence, it's important to let people know the potential risk of low arsenic concentrations on human health."

Yu-Wei Chang is a doctoral candidate in Texas Tech University's Department of Environmental Toxicology.

Past scientific studies showed that arsenic exposure led to various forms of renal dysfunction. Normally after an acute kidney injury, kidney cells regrow to recover the organ's function. However, chronic exposure to toxicants, like arsenic, injures the kidneys repeatedly and leads to the development of chronic kidney disease, an irreversible condition for which there is no current treatment.

Worse still, chronic kidney disease is progressive and leads to kidney failure. At its worst, a state called kidney fibrosis, kidney cells begin producing abnormally high levels of a protein that blocks the kidney from filtering blood, which means toxins are no longer removed from the bloodstream.

"Our study revealed that repeated long-term exposure to arsenic caused kidney cells to produce excessive amounts of proteins that results in kidney fibrosis disease," Singh said.

"Interestingly, our study also showed that these fibrosis-related changes in kidney cells can be reversed back to normal kidney cells by an FDA-approved drug that is currently used for blood cancer."

Of course, achieving such results in a laboratory is very different than achieving them in a real-world situation. Before Singh and Chang can approach the FDA to propose using the medication for kidney disease treatment, they have to clinically test both the dose and the efficacy of the drug in live patients with kidney fibrosis due to arsenic exposure.

"Our study with kidney cells is very significant in terms of identifying the arsenic-induced kidney disease and its potential cure by an FDA-approved drug," Singh said. "The limitation of this study is that this was performed with kidney cells in a laboratory condition, and this needs to be confirmed in a whole live organism, such as a rodent model and an arsenic-exposed human population."

To advance this potentially life-saving research, Singh is applying for funding from the National Institutes of Health and developing a collaboration with the O'Brien Kidney Research Core Center at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"If further confirmed with clinical trials, the findings of this study would be very significant and life-saving because, currently, there is no effective treatment to cure kidney fibrosis," Singh said.

In recognition of this important work, the Society of Toxicology awarded Chang a Renal Toxicology Award during its annual meeting, the most well-known international conference in the toxicology field.

"It's my honor to receive this award," Chang said. "It encourages us that students from Texas Tech can be outstanding among candidates from other excellent universities."

![]()

College of Arts & Sciences

-

Address

Texas Tech University, Box 41034, Lubbock, TX 79409-1034 -

Phone

806.742.3831 -

Email

arts-and-sciences@ttu.edu