Leading the Way

Alumnus Brian Thornton Isn't Letting Macular Degeneration Hold Him Back

Written 10.15.18 by Randy Rosetta

For the first 17 years of his life, Brian Thornton wasn't all that different from most young people trying to figure out life.

Eager to spread his wings. A little rebellious. Armed with a blend of hopefulness and cynicism that emanates from teenage immaturity.

Life has a way of throwing curve balls dripping with fate at unexpected times and in the most unexpected ways, though. And Thornton sure got a pitch he wasn't expecting. In his late teens, Thornton was diagnosed with dual forms of macular degeneration. Now at 42, he is legally blind with no cure currently available.

"I have both the wet and dry forms of macular degeneration," Thornton said. "In the wet form, there is a protein build-up on the macular tiles (the layers of the eyeball). In the dry form, the macular tiles sort of shrivel and die and fall off. There is a cure for wet macular degeneration. They can hit it with a laser and take the proteins off. Because of having both forms, if they hit that with a laser, that would actually knock the tiles off. I'm in a position where there is no cure for it."

What the Lubbock native and three-time Texas Tech Department of English graduate has done to manage that major hurdle is inspiring, and he is quick to credit his alma mater for playing a major role in his unconventional success story.

How impactful has Texas Tech been to Thornton? He earned bachelor's and master's degrees from the university's College of Arts & Sciences and completed a doctorate in creative writing after embarking on a journey of discovery that has carried him all over the world.

"I got all three degrees at Texas Tech because, honestly, being blind, I was terrified of leaving," Thornton said. "But staying there as long as I did taught me to not be afraid of what I could accomplish if I put my mind to it. I had a great network and the people I got to work with were absolutely incredible."

Thornton's time at Texas Tech, blended with his own resolve, helped shape a man who won't slow down because his life has become more difficult than most.

Getting Back on Track

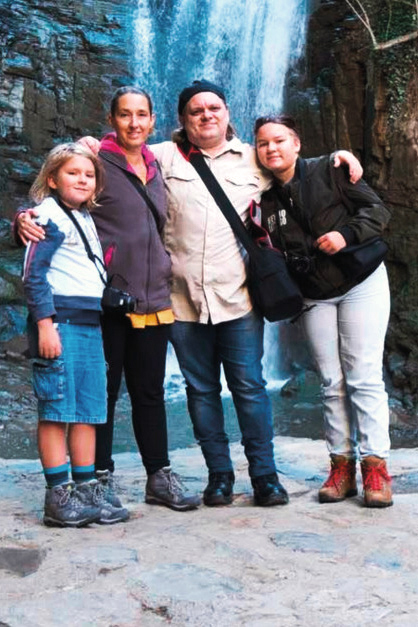

After navigating a period when he confesses to "sitting on a pity pot," Thornton picked himself up, dusted himself off and jumped back into life. He went through a divorce when he was 19, rekindled a relationship with long-time friend Nikoah Stroud, a fellow Lubbock native and Texas Tech graduate, and the two got married.

Today they have two children and live in Abu Dhabi, United Arabic Emirates, where

Thornton is an English professor.

Today they have two children and live in Abu Dhabi, United Arabic Emirates, where

Thornton is an English professor.

"She's the one who kind of kicked me in the butt and said 'Get up and do something about it,'" Thornton said with a laugh.

Those words found their mark, and ever since, Thornton has done plenty to fight back for himself and others who contend with disabilities.

Two years at South Plains College to knock out prerequisites toward a medical degree were frustrating as Thornton grappled with vision that was quickly deteriorating.

Becoming a doctor remained the goal until what Thornton describes as "a bit of a mishap in the organic chemistry lab" when he couldn't see the difference between kerosene and water during an experiment.

"I created a little bit of a minor explosion in the classroom," he said with a wry smile.

Shortly after that, SPC professor Jesse Yeh sat Thornton down and asked why he wanted to be a doctor. Thornton recited the answers he figured Yeh wanted to hear, most notably the desire to help people.

"He looked at me and said 'If you want to help one person, become a doctor: If you want to help a lot of people become a teacher,'" Thornton said. "That was kind of my awakening moment.

"I spent a lot of time trying to figure out what I could teach. I went through about 12 different majors until I realized that I really enjoy writing. In a way, it might have been settling for something, but it was something I have always loved, so it was something I didn't mind settling for. Plus, I thought to myself 'You can't really kill anybody with a poem.'"

A New Journey Begins

With an emphasis on creative writing, Thornton redirected his life and subsequently found happiness on the way to his bachelor's and master's degrees.

During those years at Texas Tech, Thornton also developed an appreciation for how well the university accommodates students with disabilities.

"Texas Tech is one of the most accessible campuses I have ever been on," Thornton said. "They have the Division for Blind Services there at the library. They weren't trying to grab your arm every time you needed help or push things to make you feel like you are an invalid."

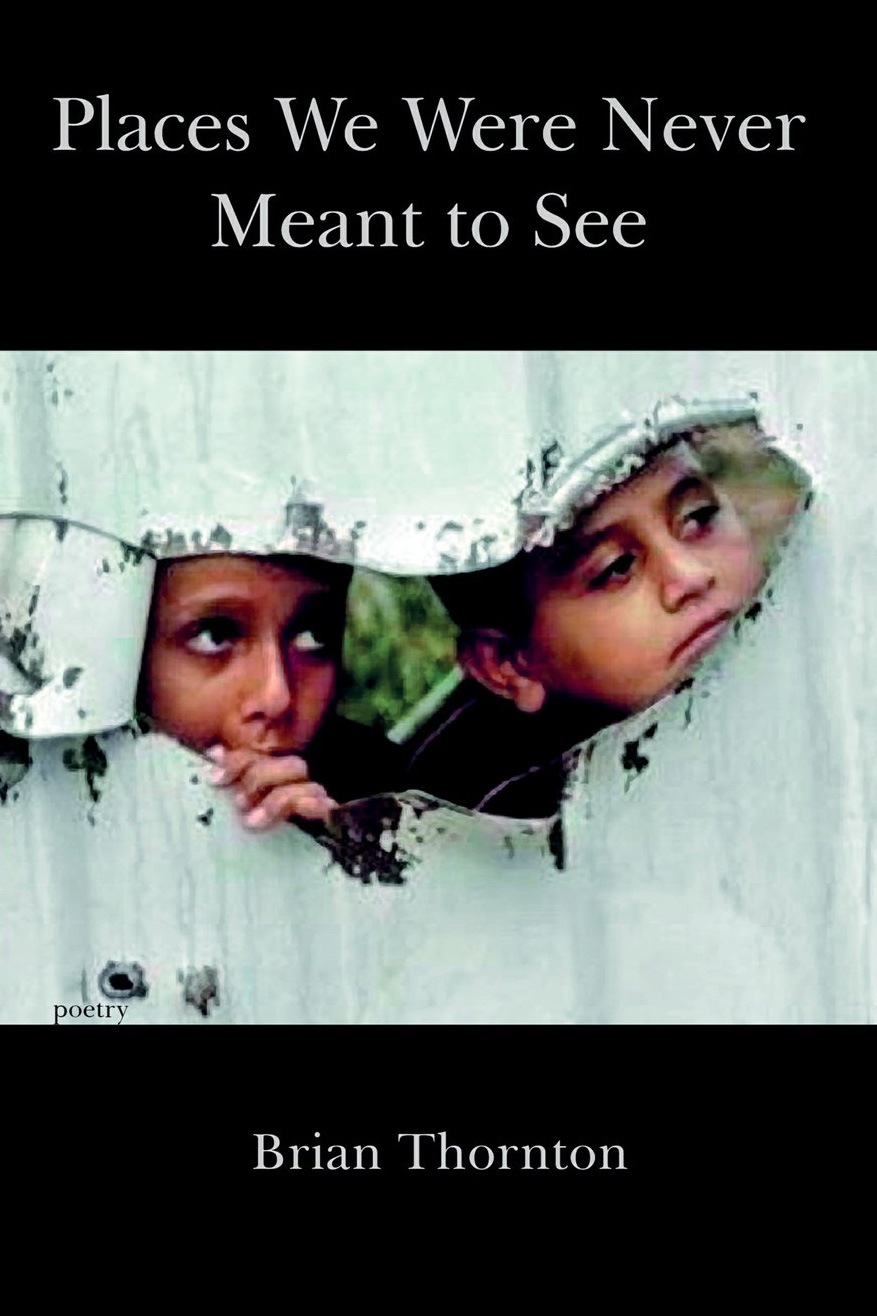

Inspired by Texas Tech English professors William Wenthe and Jacqueline Kolosov-Wenthe, Thornton forged ahead with his academic career. He tied his creative writing thesis to a book he authored, "Places We Were Never Meant to See."

"Having that first book published was one of the proudest moments of my life," Thornton

said. "That was 12 years in the making. It's the one piece that I think I have captured

really well what it means to be blind, and beyond that, what it means to define yourself

in a different way. The way that the book is laid out, only the first section is really

about blindness. The rest of the book is about discovering who you are as a person

in a group of other people.

"Having that first book published was one of the proudest moments of my life," Thornton

said. "That was 12 years in the making. It's the one piece that I think I have captured

really well what it means to be blind, and beyond that, what it means to define yourself

in a different way. The way that the book is laid out, only the first section is really

about blindness. The rest of the book is about discovering who you are as a person

in a group of other people.

"For me, the book is a reflection of not just what it is to identify myself as a blind person, but who I am now and who I hope to stay."

During his path to three degrees from Texas Tech, Thornton regularly encountered some unwanted treatment because of his condition.

The examples are numerous, but the one Thornton uses as a touchstone was when he landed in Turkey for a layover, and after he deplaned, an attendant insisted that he sit in a wheelchair for the duration of his stay in the airport.

While most offers of help are based in kindness, there is some irony attached considering how well Thornton functions.

"I feel like the way he has dealt with what he has had to, he removes all these boundaries people set for themselves," said Carly Laminack, a Texas Tech graduate who met Thornton in 2002.

She marveled at Thornton's ability to pick up an unfamiliar musical instrument and master how to play it as early as the next day—an occurrence she said she has witnessed several times.

"He makes me feel like I can accomplish anything I set my mind to. He doesn't feel sorry for himself or act like there's anything he can't do. His tool belt has more things on it than most people I know."

Which might explain why Thornton converted the frustration he felt that day in the Turkish airport into motivation. From that incident, as well as many before, Thornton created a concept that evolved into a project he recently completed: "Blind not broken."

'Blind, Not Broken'

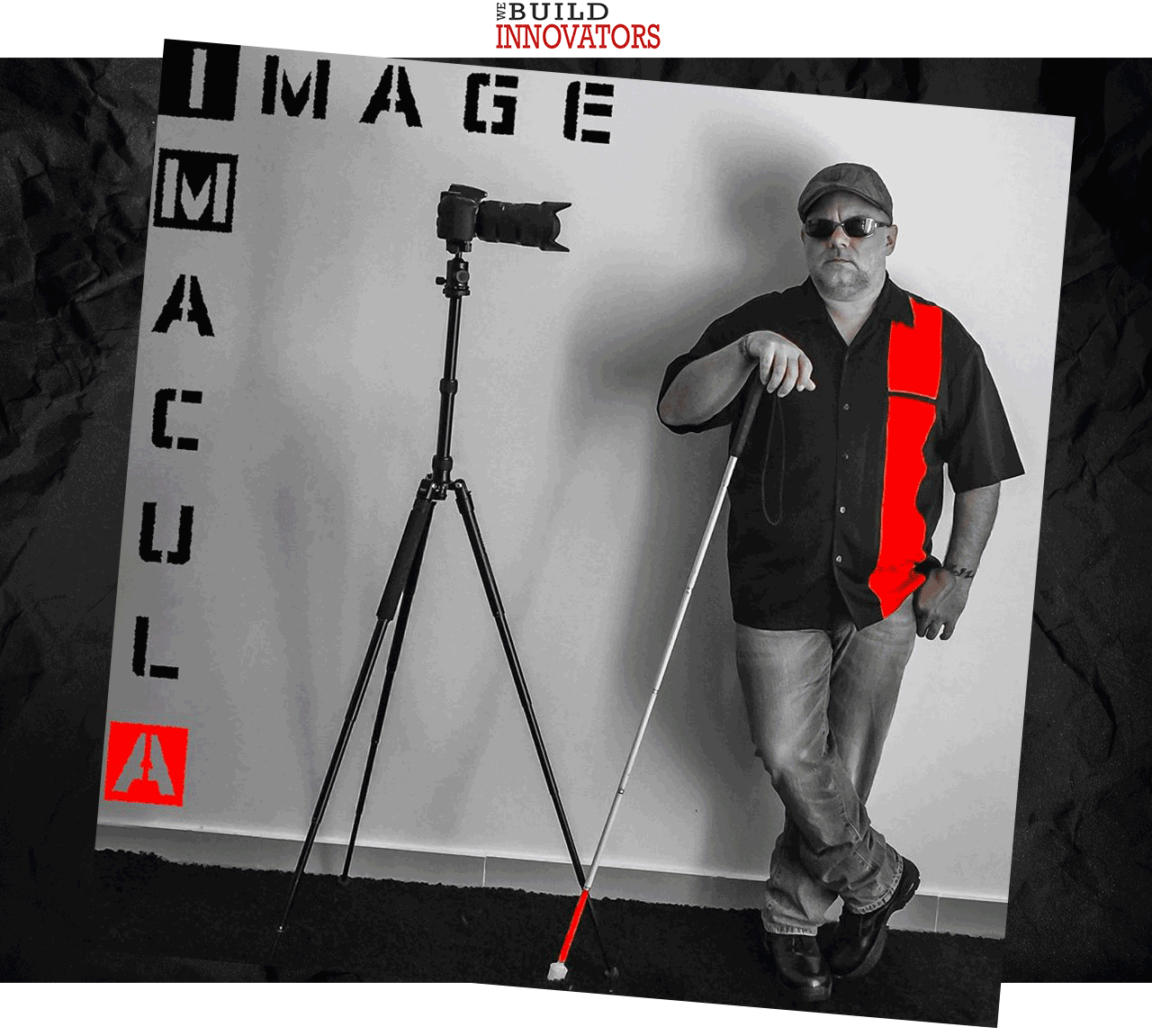

The project entailed Thornton making a trek across the wilderness of Estonia on the Oandu-Ikla Hiking Trail, then to Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Brussels and France. Along his journey, Thornton took dozens of photos of nature using equipment designed to accommodate his macular degeneration.

"I'm blind, but I am not an invalid, and that's where I came up with this concept of 'Blind, not broken,'" Thornton said.

"Being visually impaired, having macular degeneration especially, puts you in this category of not being understood. You're too sighted for the blind community and you're too blind for the sighted community. What I hope is that 'Blind not broken' can become a voice for people like me."

In the meantime, Thornton has made sure his voice has been a valuable tool in his teaching career.

He has traveled the globe to teach English and impact lives, all the while refusing to let his compromised vision get in the way. Stops in Iraq and China led him to his current job at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. There have been interesting detours.

In Thornton's bio on the Zayed University website, his exploits include "From Romani bodega-workers in Spain, to mine-clearing units in Iraq, to elephant rescue centers in Thailand and schools in China, (Thornton) has had the opportunity to share the lives of people from very diverse backgrounds."

"You wouldn't think somebody who is visually challenged could do the things he can," Laminack said. "Over the years, I've almost forgotten that he's blind. He just has this way of not letting anything stop him, and that's really pretty cool."

Discovering the Right Niche

Because there is no cure for macular degeneration, Thornton can never forget that he has different challenges. So he instead searched for the right place to use his challenges to be as impactful as he could be.

That journey took him to Abu Dhabi, where Thornton has found a niche.

"I found this job and I absolutely love it," Thornton said. "I only teach female students here, but the really cool thing is that the UAE is doing a huge push on female equality. To see the girls I'm teaching have the confidence to freely talk about their own ideas and defend their own ideas is incredible to me. It is like a drug for me to watch these girls come alive intellectually. It is a basic-level class, but it is the first time they have been asked to express their own passions, their own feelings, their own thoughts and ideas."

Finding a new way to function is certainly something Thornton has mastered. As far as he can tell, straight-forward is the best approach to whatever path you are destined to take.

"I am very open with the girls I teach," Thornton said. "The first thing I do is talk about my visual disability. I laugh about it. I also am open with the fact that I wasn't always the best kid when I was growing up. I'm the heavy-metal rocker professor. The one covered with tattoos.

"I know what it's like to be cast aside and what it takes to get back up and keep living your life. I am in no way going to try and lead a revolution in the Middle East, but I do want them to know that there are ways to make yourself known and make yourself heard and to get ahead.

"I am one of these people that doesn't like dancing around disabilities. I would rather tell them, 'Hey I'm blind. Here's what I can do. Here's what I need help with.' I'm all for that. I think this whole hiding and not being able to talk about your disability is a big mistake."

Turning Disability Into Inspiration

Thornton has learned to avoid that mistake and instead categorizes his condition as inspiration—calling the loss of sight "one of the most defining moments of my life."

"I'm not a very religious person, but at the same time I believe that things happen for a reason," Thornton said. "I think what happened to me happened at a time when it needed to happen. It's kind of what turned me around and got me in gear and gave me a direction for what I needed to do with my life."

The latest chapter of Thornton's extraordinary life gave him an opportunity to combine an inherited passion for photography with another chance to accentuate his knack for overcoming life's odds.

Mixed in is a chance to honor his late father.

Gary Thornton owned Thornton's Vacuum Center in Lubbock and had a passion for photography – which he shared with his son. Three years ago, Gary Thornton died suddenly from cancer, and Brian Thornton's latest endeavor is a tribute.

The still untitled book—Thornton said it will be something along the lines of 'The stars we hang by hand'—will be a blend of photography and his poetry. A concoction of "ekphrastic poetry and the work of a blind man trying to paint pictures with photography," he said.

According to www.PoetryFoundation.org, an ekphrastic poem is a vivid description of a scene or, more commonly, a work of art. Through the imaginative act of narrating and reflecting on the "action" of a painting or sculpture, the poet may amplify and expand its meaning.

"He was a wedding photographer and never really got poetry," Thornton said of his father. "So this book I am working on is poetry about the images. Since I can't see what's always around me in the landscape, I am able to do my photography, get home, and as I am processing it, I am actually experiencing it in a different way for the first time. I can take notes on that, and what becomes the actual poem about the image is that secondary experience."

An Ongoing Emotional Battle

Gaining new experiences has been a major theme in Thornton's life ever since he began bouncing back from the hand he was dealt.

What he has managed to navigate despite considerable challenges is easy to admire. As courageous as every step down that road has been, though, Thornton has wrestled with emotions you would expect a man who lost his sight to wrestle with.

"There are times when I do feel broken because I am blind," Thornton said matter-of-factly. "When I was hiking through Estonia, there were times when I was saying to myself, 'Why am I doing this?'

"Looking back on things that happened, a lot of the brokenness has nothing to do with my eyes. It has to do with the psychology. It has to do with understanding who you are and what you are capable of. There have often been times that I have to tell myself, 'Wait a minute: Remember, you are not broken.'"

What is Macular Degeneration?

Macular degeneration is the leading cause of vision loss, affecting more than 10 million Americans—more than cataracts and glaucoma combined.

At present, macular degeneration is considered an incurable eye disease. It is caused by the deterioration of the central portion of the retina, the inside back layer of the eye that records the images we see and sends them via the optic nerve from the eye to the brain. The retina's central portion, known as the macula, is responsible for focusing central vision in the eye, and it controls our ability to read, drive a car, recognize faces or colors, and see objects in fine detail.

The specific factors that cause macular degeneration are not conclusively known, and research into this little understood disease is limited by insufficient funding. At this point, what is known about age-related macular degeneration is that the causes are complex, but include both heredity and environment. More information is available by contacting the American Macular Degeneration Foundation.

College of Arts & Sciences

-

Address

Texas Tech University, Box 41034, Lubbock, TX 79409-1034 -

Phone

806.742.3831 -

Email

arts-and-sciences@ttu.edu