Into the Petri Dish

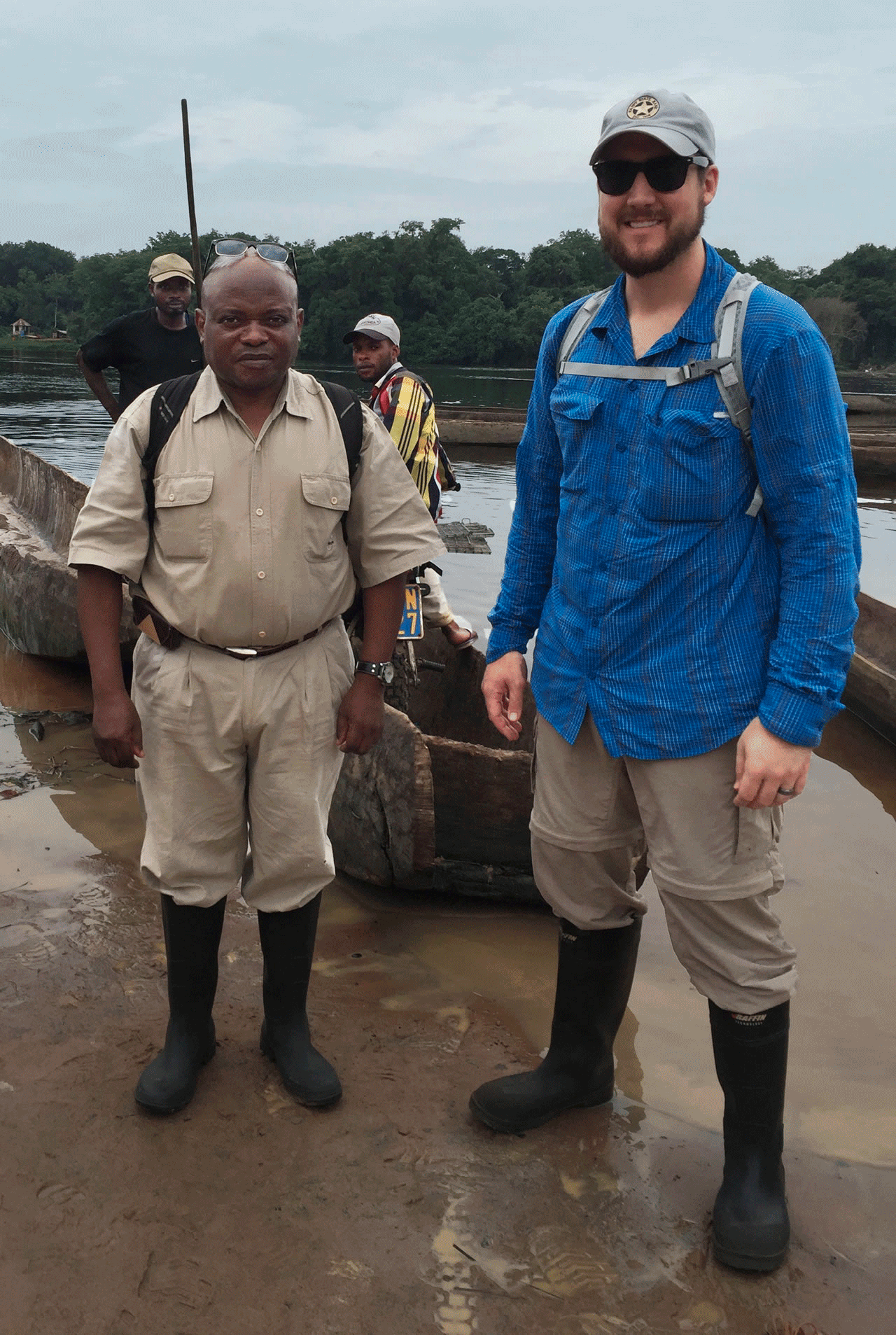

CDC microbiologist Matt Mauldin (right), Professor Jean Malekani of the University of Kinshasa (left), and their team are about to cross the Tshuapa River at Boende, Democratic Republic of Congo, to conduct research in neighboring villages. Photo courtesy Mauldin/CDC.

Why Conduct Research Abroad?

3.3.2020 by Toni Salama

Texas Tech University alumnus Matt Mauldin (BS Biology, 2008; PhD Biology, 2014) is a microbiologist in the Poxvirus and Rabies Branch at the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an arm of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Like many other CDC scientists, Mauldin has traveled much of the world in search of the reservoirs, or sources, of deadly infectious diseases.

The best place to stop the next disease outbreak is at its source, says Mauldin, who speaks of a one world, one health approach to prevention.

"I have been asked repeatedly why the CDC conducts so much work outside of the United States. But the truth is, in this age of global travel we are all highly connected," Mauldin says. "That truth extends to plant and animal life around the world. Habitat modification can alter how animals and humans interact, potentially leading to disease spillover, which could subsequently lead to exported cases."

Most newly discovered human pathogens are zoonotic in nature, meaning they are capable of infecting both animals and humans, Mauldin explains. In fact, CDC materials say that six out of every 10 infectious diseases in humans are spread from animals.

Transmission by Importation

In some instances, importing animals from abroad has proven to be a source of infection.

One example: a 2003 shipment from Ghana of rodents infected with Monkeypox, a poxvirus that was first documented in humans in 1970. The imported African rodents were housed closely with prairie dogs, which acquired the virus and in turn infected some 37 people in the United States who had bought the prairie dogs as pets.

At work in the CDC's BSL-4 lab, Mauldin sits in a biosafety cabinet (primary containment) wearing a positive-pressure suit. He's adding Formalin Crystal Violet (CV) Stain to a 6-well tissue color plate. The technique inactivates viruses during in vitro studies. The only virus studied in the BSL-4 is Variola virus, the causative agent for smallpox. Photo courtesy CDC.

Because of that incident, a moratorium was put in place regarding the importation of African rodents into America, says Mauldin, who was not a member of that particular research team.

The 2003 Monkeypox outbreak did have a silver lining, though.

"There were no deaths, and the CDC determined the disease progression in prairie dogs was similar to that in humans," Mauldin says. "We actually use that animal model now for proof-of-concept studies examining Monkeypox medical countermeasures."

Unfortunately, not all outbreaks end so well.

Transmission by Tourism

As critical as it is to find the animal source of a disease, there are human factors—from economic necessity to cultural practices to naive wanderlust—that also influence the who, when and where of the next infection.

Case in point: Marburg hemorrhagic fever, a virus similar to Ebola. The CDC reports that Marburg, although relatively rare in humans, from time to time has been laboratory-confirmed throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Many of those outbreaks started among miners while working in mines populated with the African fruit bat Rousettus aegyptiacus. "The virus is then transmitted within their (the miners') communities through cultural practices, under-protected family care settings, and under-protected health care staff," say CDC materials.

CDC ecologist and TTU alumnus Brian Amman and his research group tracked the reservoir of Marburg hemorrhagic fever to its source in Uganda's Python Cave. Photo courtesy Amman/CDC.

The same species of bat also roosts in Uganda's Python Cave, which was a tourist attraction until two foreign tourists contracted Marburg hemorrhagic fever after exploring the cave in 2008. One, a traveler from the United States, toured the cave in January that year. She didn't exhibit symptoms until she was home for several days; although a Marburg diagnosis was months in coming, ultimately she survived. Unfortunately, a traveler from the Netherlands who visited the cave a few months later in July didn't survive; she returned home and died of the virus. Python Cave was closed to visitors in August 2008.

RELATED ARTICLE: "Very Sick, and Now a Curiosity" — The New York Times.

Transmission by Organ Transplant

When diseases do originate in the United States, some that are transmitted from one

human to another may have had their genesis in an animal host.

Even transplant recipients have fallen victim to deadly viruses, with the donor—and

the donor's contact with an infected animal—being the common denominator.

A research paper published in The New England Journal of Medicine reported that in 2004, doctors at a hospital in Texas diagnosed rabies virus in three transplant patients who had received a liver and two kidneys from a common organ donor. Later, they discovered the rabies virus also had developed in a fourth transplant patient who received a vascular graft from the same donor during liver transplantation.

All four recipients died within 50 days of transplantation. Initial diagnostic evaluations revealed no cause for the rabies virus, the research paper stated. However, investigations conducted after rabies virus was diagnosed in the recipients revealed that the donor, who died of an unrelated cause, purportedly had been bitten by a bat and that antibodies against rabies virus had been present in the donor.

Texas Tech University alumnus Brian Amman (PhD Zoology, 2005), a CDC ecologist with the Viral Special Pathogens Branch, Virus Host Ecology Unit, remembers working on a 2005 case in Massachusetts and Rhode Island where a pet hamster was connected to the deaths of three organ-transplant recipients and the illness of a fourth.

Amman's research showed that all four patients had received transplanted organs from a single donor who had been exposed to a pet hamster infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). His research group traced the hamster through a Rhode Island pet store to a distribution center in Ohio. More LCMV-infected hamsters were discovered in both the pet store and the distribution center.

As Mauldin puts it: "The health of the environment and human health are inextricably linked."

![]()

College of Arts & Sciences

-

Address

Texas Tech University, Box 41034, Lubbock, TX 79409-1034 -

Phone

806.742.3831 -

Email

arts-and-sciences@ttu.edu