Leading the Way

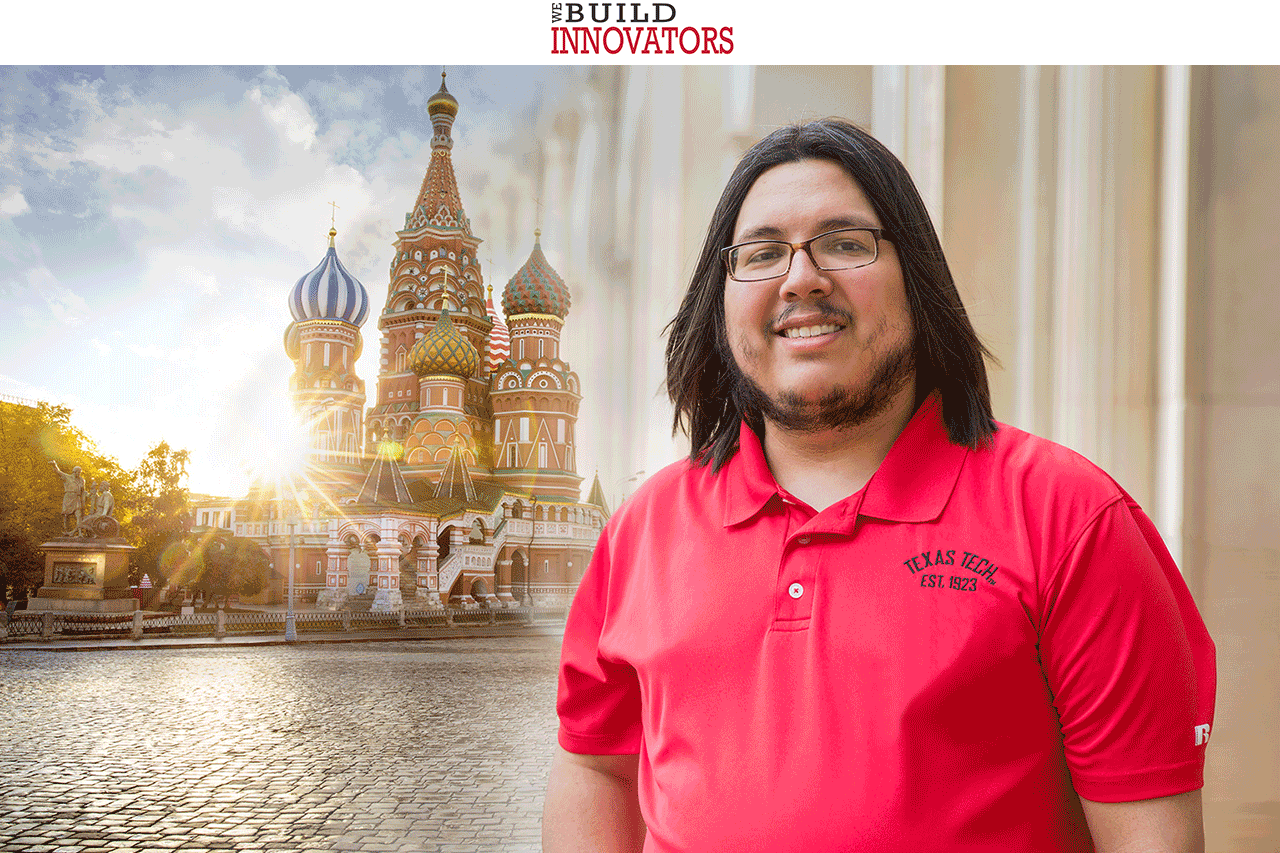

Nicholas Acosta Wins Fulbright To Teach English in Russia

Written by Amanda Bowman

Kids in schoolyards across the world have dared one another to do silly things, like telling an unrequited love about a crush. Some people dare to jump out of airplanes or sing in front of a group of strangers. For Nicholas Acosta, an adjunct instructor of applied linguistics in the Department of Classical & Modern Languages & Literatures, a simple dare changed the course of his academic trajectory.

While pursuing his bachelor's degree in economics at Texas Tech, Acosta and his friends were discussing foreign language classes.

"One of my friends was taking Japanese, another was taking Italian and another was taking Spanish," Acosta said. "Then, they said, 'You should take Russian,' and I said, 'OK, I'll do it.'"

From Economics to Russian

Once Acosta completed his bachelor's degree, he obtained his master's degree in economics through Texas Tech's Graduate School. Still wanting to further his education, Acosta stayed at Texas Tech and enrolled in the applied linguistics master's program. Transitioning to the applied linguistics program took some adjusting, but Acosta was able to make it work.

"It was a bit of a switch because, in economics, it was all mathematics and things were done differently," he said. "When I switched to applied linguistics, it was a different atmosphere. There was still a lot of hard work. In economics, you're only given so much work, but the work was very hard. In applied linguistics, the work wasn't as hard as it was in economics, but the workload was very high."

By the time he began in the applied linguistics program, he already had taken three years of Russian. He also learned the Cyrillic alphabet fairly quickly.

"I was taught the Cyrillic alphabet in a week," he said. "I would practice writing out all the letters all the time in my workbook. Even if the class wasn't focusing on the alphabet, I would still have practice in my homework and quizzes over the alphabet. I had to produce all 33 letters."

Acosta also was able to practice speaking Russian with a classmate.

"I lucked out in my economics department because we had a Russian speaker," he said. "She was working on her master's and we often chatted in Russian, so that was beneficial."

Applying for the Fulbright

Acosta first heard about the Fulbright U.S. Student Program through an email.

"There was a list of all different types of fellowships, grants and everything," he said. "I saw that the Fulbright Program was on there. I also had heard about the Fulbright Program from a couple of my colleagues. I have one friend from Brazil who was a former Fulbright student. She told me, 'Yeah, if you apply to that, it'll be really good.' I said, 'Okay, I'll look into it.' And I did.

"I got in touch with Wendoli Flores, the director of the National and International Scholarships & Fellowships Office in the Honors College. I filed a letter of intent, which is what you have to do first, and then you wait

a little bit until the application opens up."

Acosta applied for an English teaching assistantship in Moscow. Though competition

was fierce, he was selected as a Fulbright recipient.

"I will be teaching English as a second language while also doing a cultural unit with Russian speakers to help them understand American culture a little bit more," Acosta said. "I'll focus more on American movies and books, and maybe some music, art and poetry."

Acosta will be in Moscow for an academic year beginning this fall. He's still uncertain of the university where he will teach, but he hopes to go to Moscow State University.

Fluency

Asking someone if they're fluent in more than one language can result in a complicated answer, Acosta said.

"From an applied linguist point of view, it depends on the genre," he said. "So let's take a look at a specific topic. For example, I would say I'm more fluent when I'm speaking about myself, what I like to do, what my hobbies are, what I do in my free time and my job. Give me a topic, let's say biology or accounting. No, forget it. That even happens in English, too."

One thing students trying to learn a new language shouldn't do is focus solely on grammar, Acosta said.

"A lot of language programs, especially in high schools and middle schools, focus on just teaching grammar," he said. "I learned that you have to give students a goal, like how are they going to use the language? Give them a specific, communicative task with a communicative goal based on a real-life scenario: How will you use this? So, instead of focusing on a topic, like reflexive verbs, tell them, 'Let's do your daily routine,' and then give them only what they need so they can work with how they would say their daily routine in the target language, which is, I would say, much more realistic.

"I think students would benefit more from that, and they remember the language much better. The research has shown this type of approach has worked better than just teaching grammar. I could teach students grammar all day, but if I don't teach them how to use it or when to use it, then what's the point? The overall goal, especially for applied linguists, is meaning over form."

Interference

In applied linguistics, a person's first language is referred to as L1. The second language someone learns is referred to as L2, and so on. When learning an L2, you can come across what applied linguists call interference. Interference is when the "rules" of one language interfere with the rules of another, something Acosta experienced while learning French.

"I had some interference when I was starting my L3, which is French," he said, "but I had some L2 interference, because in Russian, we don't use the present tense of the verb 'to be.' So I was constantly skipping the verb 'to be' in French. That happened for a while, then I managed to finally quit, then it appeared again. Russian doesn't use articles. You need the articles in French, and I would constantly omit them. So it appears more often than people think. And it's also a very natural part of learning. But what happens is, I think learners get frustrated when that happens."

Sociolinguistic Competence

Learning a new language is more than just being able to read, write and speak. The

cultural aspect of a language and the country in which it's spoken also are vital.

"Just because you know what is possible in a language and you can do it, whether it's

grammar or vocabulary, there are times when you shouldn't do it," Acosta said. "This

has to do with sociolinguistic competence or, as one of my professors called it, pragmatics.

Context is very important. Depending upon a situation, using a specific structure

in one context can mean something else in another. Knowing when to use a specific

structure is necessary in order to avoid trouble. This also expands to cultural elements

such as manners, customs and behavior."

Examples of such contextual and cultural difference can include simple things like facial expressions and gift giving.

"One of the things you never do in Russia is smile all the time," Acosta said. "Russians don't smile unless they have a reason. Another cultural difference is you should never give knives to a friend. We give knives as presents to each other in the U.S., but Russians don't do that. That's considered a bad sign. If you give a friend a knife as a present, that means that the ties that bind you, the ties of friendship, will be cut."

Benefits of Learning a New Language

Being able to speak more than one language not only allows people to go to new countries and interact more easily with native speakers, but it also keeps your brain active as you grow older.

According to a study published in The Journal of Neuroscience, people who grow up bilingual maintain youthful cognitive controls as they age. However, being bilingual also helps people during their younger years, too.

"Knowing a second language when kids grow up helps them with their decision-making skills, and they'll be more cultural," Acosta said.

There also is still hope for adults.

"A lot of people believe children have an advantage of learning a second language than adults do," Acosta said. "Children learn a new language at a much faster rate, and they absorb it much better, but the thing about it is, adults do have an advantage when it comes to learning a second language. It's because they possess something children do not have, metacognition and decision-making skills.

"Anyone who thinks, 'Oh, no, I didn't learn a new language when I was little, so it's too late for me.' No, it's not. It's never too late to learn a second language. It never is."

About the Fulbright U.S. Student Program

The Fulbright U.S. Student Program is one part of the Fulbright Program. It was established in 1946 under legislation introduced by then-Sen. J. William Fulbright of Arkansas and is sponsored by the U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs.

The Fulbright Program awards approximately 8,000 grants annually. Roughly 1,600 U.S. students, 4,000 foreign students, 1,200 U.S. scholars and 900 visiting scholars receive awards, in addition to several hundred teachers and professionals.

College of Arts & Sciences

-

Address

Texas Tech University, Box 41034, Lubbock, TX 79409-1034 -

Phone

806.742.3831 -

Email

arts-and-sciences@ttu.edu