Meet Miranda Andrews

Chemistry PhD student Miranda Andrews tests a color-change liquid.

Chemistry PhD Student Andrews Dishes the Stats on Sexism in STEM

Story by Toni Salama

Miranda C. Andrews is a PhD student conducting research on photoswitchable molecules in the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry. She's a teaching assistant and a member of Assistant Professor Anthony Cozzolino's Research Group in (Supra)molecular Inorganic Materials.

The latest news out of the Cozzolino Research Group (March 2018) is that Andrews' paper was accepted to the journal Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences. To quote the news brief: "An intimate electronic link between two different photoswitches and a carboxamidine (a good coordinating group for metals) was demonstrated by measuring a change in the oxidation potential of the carboxamidine as a function of the state of the photoswitch. We are working on metallating these to probe the effect on the redox potentials of metals." (As soon as the group learns of the publication date, a link will be provided on their site.)

That would be news enough for any young scientist. But Andrews conducts additional, and very different, research as well and presents it to other scientists—borne out of her own run-ins with attitudes and behavior patterns encountered by many women in just about any setting: sexism.

Not a Forbidden Subject

Andrews gave her first sexism presentation to an audience of chemists at the Southwest Regional Meeting (SWRM) of the American Chemical Society (ACS) on Oct. 31, 2017. That was followed by an invitation to adapt her talk to a STEM audience here on the Texas Tech campus. She gave that one, titled "STEMinar: A Millennial's Perspective on Sexism in STEM," on Feb. 19 to a group that met in the TTU Library. That afternoon, the come-and-go audience of 18 to 20 people—mostly faculty—had near equal attendance of 9 males and 9 to 11 females. Their questions and comments had to be cut short in the interest of time. Andrews gave a second STEMinar on Feb. 21 to #WomeninWind in Holden Hall.

The research that Andrews conducted for her talk was done at an interesting time, she says, given that the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements have taken root recently in every field. These movements, Andrews says, address the more overt or explicit biases that women have faced and continue to face.

"On the one hand, I'm encouraged that these movements have empowered women in every field to come forward with their stories of harassments and assaults. On the other hand, this research has shown me that implicit bias, which starts so early for most people, still dictates how we perceive and judge others and ourselves," Andrews says. "This seems to hold particularly true in the STEM fields. If the 'leaky pipeline' of STEM and academia is ever going to be fixed, we all have to do a better job of taking stock of the shortcut thoughts that we use to measure others' abilities, strengths, and weaknesses."

"Leaky pipeline" is a term used to describe the pattern of females leaving the STEM disciplines as they advance through their academic and professional lives.

In describing her talks, Andrews writes that, "While instances of blatant sexism still occur, they seem few and far between. Most of the sexism that is experienced by young women today is a result of implicit bias, those thoughts that we as a society grow up learning to have. The STEM field in particular is full of opportunities for young women to wonder, 'Did that happen because I am a woman or am I just imagining things?' This is a good sign, but it also means that the work we have to do to level the playing field for women in science will be that much harder. We have to root out that implicit bias, which is one of the most difficult types of bias to overcome."

One test for implicit bias comes in the form of a riddle: A desperate father rushes his severely injured son to the emergency room. The ER surgeon is ready to operate but ethically cannot, saying, "This is my son." What relationship does the surgeon have to the injured boy? Andrews said in her STEMinar that this riddle even had her stumped, at first, a few years ago.

The Proof is in the Research

So, armed with charts and statistics, Andrews generously shares the wealth of evidence on gender bias that is her "STEMinar: A Millennial's Perspective on Sexism in STEM" slide presentation at this link. But to detail two of her examples here:

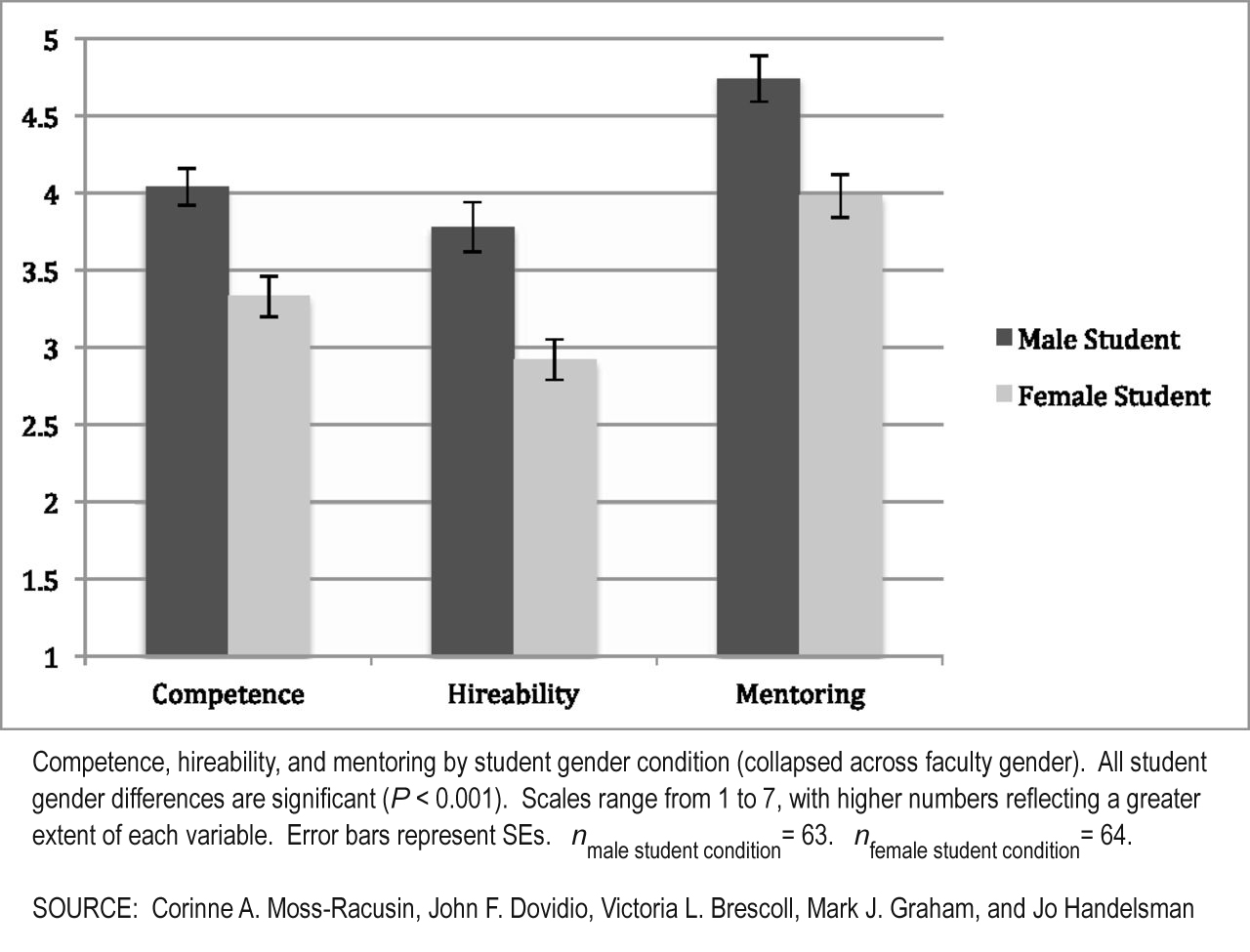

A study by Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, John F. Dovidio, Victoria L. Brescoll, Mark J. Graham and Jo Handelsman published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), titled "Science Faculty's Subtle Gender Biases Favor Male Students."

This 2012 study acknowledged that various lifestyle choices likely contribute to the gender imbalance in science, but sought to investigate whether faculty gender bias exists within academic biological and physical sciences, and whether it might exert an independent effect on the gender disparity as students progress through the pipeline to careers in science. According to the abstract, the experiment specifically examined whether, given an equally qualified male and female student, science faculty members would show preferential evaluation and treatment of the male student to work in their laboratory.

In that randomized double-blind study, 127 faculty members in biology, chemistry and physics at research-intensive universities were to rate the job application materials for a student lab manager with undergraduate degree. The materials for this fictional applicant were identical, with the exception that 63 applications were given a male name and 64 were given a female name. Results showed that the applicants with the male names were rated higher on competence and hireability, and showed a greater willingness on the part of faculty to provide mentoring, than the applicants with the female names. (According to the abstract, "[t]he gender of the faculty participants did not affect responses, such that female and male faculty were equally likely to exhibit bias against the female student. Mediation analyses indicated that the female student was less likely to be hired because she was viewed as less competent.") Also, the mean starting salary of $30,238.10 offered to the applicants with the male names was significantly higher than the mean starting salary of $26,507.94 offered to the applicants with the female names.

Some of the results of that study appear in the following figure:

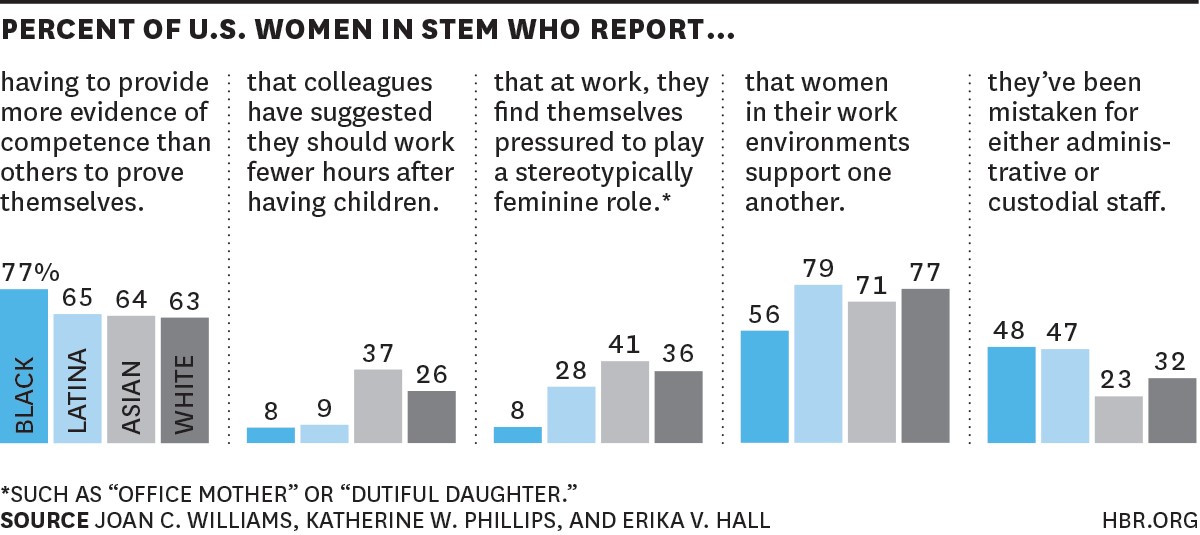

A study by Joan C. Williams, Katherine W. Phillips and Erica V. Hall published in Harvard Business Review (HBR), titled "The Five Biases Pushing Women Out of STEM," based on their 2014 study, "Double Jeopardy? Gender Bias Against Women of Color in Science."

Williams wrote in the HBR article that the old argument of low numbers of American women in STEM being a pipeline issue is not convincing; it's no longer a matter of just interesting more young girls in STEM subjects and the issue will resolve itself over time. Neither did she buy the theory that women are choosing to forgo careers in STEM to attain better work-family balance. Evidence for that, she wrote, is thin.

Williams, Phillips and Hall added their research to what Williams called "a growing body of evidence that documents the role of gender bias in driving women out of science careers." They conducted in-depth interviews with 60 female scientists and surveyed 557 female scientists, both with help from the Association for Women in Science, she wrote. "These studies provide an important picture of how gender bias plays out in everyday workplace interactions. My previous research has shown that there are four major patterns of bias women face at work," Williams wrote in the HBR article. "This new study emphasizes that women of color experience these to different degrees, and in different ways."

Some of the results of that study appear in the following figure:

There's Still Work to be Done

Meaningful changes academics can make right away, Andrews says, are in the journal peer-review process and in the standards of scientific organizations.

Currently, when research papers are submitted to journals, the process is single-blind: the reviewers know who is submitting the paper, but the person submitting the paper doesn't know who the reviewers are. Andrews quoted Dr. James M. Gentile on the danger of scientists assuming gender bias as something that other people do, somewhere else.

"It's easy for science faculty members, convinced of their own high ethical standards, to assume that gender discrimination lies outside of their actions: earlier in the pipeline; in other fields; at other types of institutions," Gentile wrote in a Scientific American blog entitled "Gender Bias and the Sciences: Facing Reality." The self-described former dean of natural sciences at a liberal arts college allowed that such bias might hold true at universities, but that such could not be possible at a liberal arts college.

Gentile related his query of colleagues to analyze the percentage of women with professorships of all types at the 30 highest-ranked liberal arts colleges. They came back, he wrote, with the following percentages of women professors of all ranks thusly: biology 45%, chemistry 35%, astronomy 33%, and physics 25%.

Beyond gender bias, overt, explicit behavior in the form of sexual harassment and assault is still a threat. One place to address that is on campus; another is through scientific organizations, as Andrews showed via an article in Chemical and Engineering News (C&EN), titled "Confronting Sexual Harassment in Chemistry."

The article dug deep into testimonies of numerous women who were sexually harassed or assaulted by those in a position of power over their study, their research or their careers in a university/academic setting—and underscored their ability, or more often the lack thereof, to fight back, rally support, stand up for themselves, find some way out.

The article also went on to list how some scientific societies are taking a stance on sexual misconduct—or not so much.

Andrews made bullet points of examples from the American Geophysical Union (AGU), the Entomological Society of America (ESA), and the American Chemical Society (ACS), of which she is a member.

The AGU has begun classifying sexual misconduct as scientific misconduct and is revising its code-of-conduct policy for meetings to reflect this change. The article quoted AGU President Eric Davidson as calling it a "pretty big move," considering that "Historically, scientific misconduct has primarily been looked at through such things as plagiarism and falsification of data..."

The ESA, according to the article, which had incorporated language about sexual misconduct into its code of conduct, received its first report of sexual harassment at its 2014 conference. In 2016, a report came in about the same perpetrator. "After our initial review of the complaints, we notified the member that if they did something similar at a future meeting, we would ask them to leave and not return to future meetings. In another meeting, we had to take that step after receiving a new complaint," the article quoted Rosina Romano, ESA's director of meetings, as saying.

The ACS's Volunteer/National Meeting Attendee Conduct Policy includes language about sexual harassment. "Harassment of any kind, including but not limited to unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment will not be tolerated," the article stated, going on to report that "ACS General Counsel Flint Lewis says that since this revision, there have been 'a handful' of reported incidents that required an investigation. 'In one extreme case, we barred somebody from a national meeting for a year,' he says."

During her talk, Andrews wondered aloud what that extreme case might have involved. Some in the audience wondered right along with her.

A Future Worth Fighting For

Andrews believes strongly in her future and that of other scientists who happen to be women. She's especially interested in chemical education.

"I would like to pursue a ChemEd post-doc position when I'm done here, so that I can learn how to study people, their learning processes, and the best ways to teach to those methods of learning," she says. "After that, I want to teach at a university. Universities are intersections of so many cultures and research topics; they are some of my favorite places to be."

![]()

College of Arts & Sciences

-

Address

Texas Tech University, Box 41034, Lubbock, TX 79409-1034 -

Phone

806.742.3831 -

Email

arts-and-sciences@ttu.edu