Into the Petri Dish

CDC ecologist and TTU alumnus Brian Amman (foreground) enters Uganda's Butagota Cave to conduct an ecological investigation of and during an outbreak of 'Sudan Ebolavirus', a strain of Ebola. Photo courtesy CDC.

Biology Program Readied 5 Alumni for Careers at CDC

3.3.2020 by Toni Salama

Ebola. Hantavirus. Marburg. Plague. Smallpox. Few other words in the English language have equal power to raise fear in a population. When there's news of an outbreak—or in the case of Ebola even a single infection—the average person wants to get as far away as possible. Only a courageous few track deadly pathogens to their place of origin, or "reservoir" in disease parlance, and research ways to reduce the risk of future epidemics. These are the scientists of the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an arm of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Five of them earned their degrees from Texas Tech University's Department of Biological Sciences, and all five are veterans of Robert Bradley's biology lab and field work expeditions.

Bradley, a biology professor and director of the Natural Science Research Laboratory (NSRL) at the Museum of Texas Tech University, says of their training: "We must be doing something right."

Although Bradley can recount the successes of all of his master's and Ph.D. students, the five who now work at the CDC were hired, he says, because of their experience before graduation: sampling animals in the field at the site of an outbreak, lab work in molecular biology and genomics, and poise when communicating their findings to scientific groups.

Of the five, Brian Amman (PhD Zoology, 2005) and Matt Mauldin (BS Biology, 2008; PhD Biology, 2014) are at this moment conducting research that puts them at the forefront in the battle against the Ebola-like Marburg virus, smallpox, and coronavirus.

Ecologist Brian Amman

Brian Amman, now home from back-to-back trips to Sierra Leone and Uganda, is a CDC

ecologist with the Viral Special Pathogens Branch, Virus Host Ecology Unit. Even before

he successfully defended his doctoral dissertation in May 2005, Amman already had

landed a job as a mammalogist with what the CDC then called the medical ecology team.

In 2007, his research group solved a 40-year-old mystery by discovering the natural reservoir for Marburg hemorrhagic fever.

He credits that and other achievements to the work ethic, perseverance and attention to detail that he acquired at Texas Tech.

"Dr. Bradley ran a real tight ship, and there was a right way to do things," says Amman. "Through the TTU biology department and Dr. Bradley's lab, I learned how to organize and conduct field work centered around trapping, identifying and sampling small mammals, some of which involved zoonotic viruses, or those viruses that can be transmitted from animals to humans."

Amman now instills those same practices in his own field teams and in the local wildlife officials he trains to carry on the work of trapping and tagging animals, collecting samples and sending them to CDC labs for analysis.

Many a Bradley field trip has taken place in similar locations—remote, no cell phone reception, and no facilities beyond what the group brings with them: food, tents, and a camp stove. In addition to learning the biological ropes of trapping and sampling animals, those on a week-long field trip stand a fair chance of getting their work done in spite of flat tires, pouring rain, flooded campsites, or even a hungry bear—thus developing some very practical problem-solving skills in the bargain.

For the average molecular biologist, with no field training, that would be a very new experience, Bradley says.

"But if you take one of our students and drop them in Democratic Republic of Congo and say, 'Go out and catch some primates, and by the way, you're going to live in this village for two weeks while you're doing that,' then it's not an unknown to them," Bradley says. "They've been there, done that."

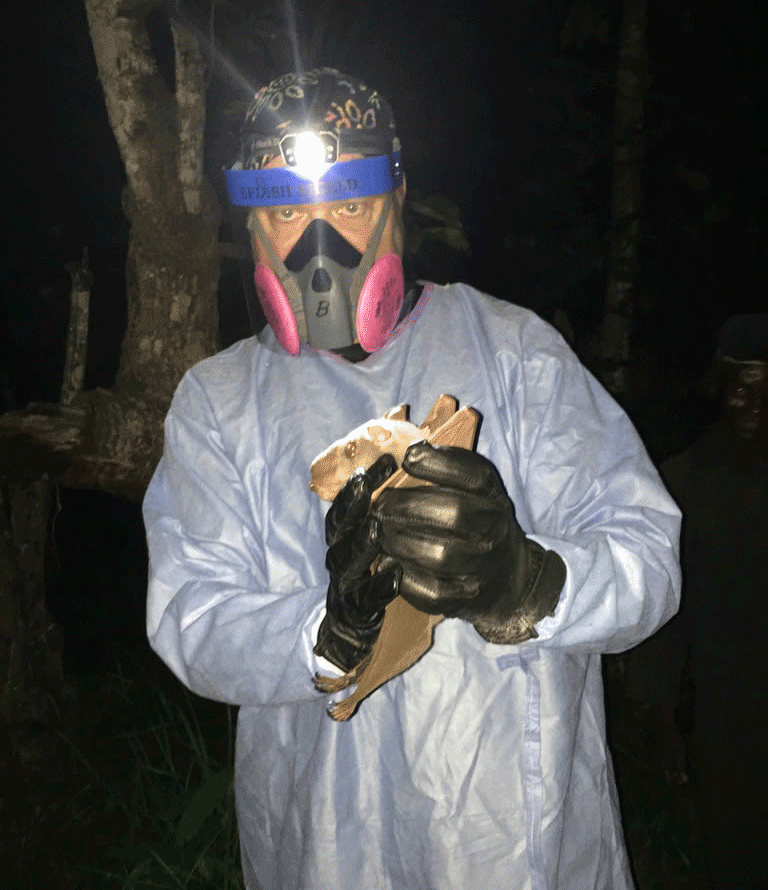

Amman holds a hammer-headed fruit bat (Hypsignathus monstrosus) caught along the Moa River outside of Tailu Village, Sierra Leone, near the border with Guinea. Photo courtesy Amman/CDC.

Amman couldn't agree more.

"All the long hours in the field with Dr. Bradley and my lab mates also taught me to be efficient and organized, which makes almost every situation in my job now easier and safer," Amman says. "There was a great sense of teamwork and comradery in our lab that I cherished while I was at Texas Tech. It is important to know that you can count on every single individual on your team to do what they are supposed to do."

Dangerous Work

Field work, even lab work, exposes CDC researchers to deadly pathogens. Between 1976 and 2019, outbreaks of Zaire ebolavirus, Bundibugyo ebolavirus and Sudan ebolavirus have been responsible for 12,977 confirmed deaths worldwide. Excluding cases where only a single individual contracted the virus, Ebola's average mortality rate is about 60%; and it continues to be a serious threat.

"There's a major outbreak of Ebola in West Africa right now," Bradley says, "but it has fallen off the radar because of the coronavirus news."

Looking for Ebola virus, Amman (foreground) examines a Beuttikofer's Epauletted Bat (Epomops beuttikoferi) at a field lab in Kailahun, Sierra Leone. Photo courtesy Amman/CDC.

Historically, in 2014 alone—Ebola's worst year on record—the virus took the lives of 11,261 people in seven countries; two of them died in the United States after contracting the disease abroad. In 2004, a lab worker in Russia died of Ebola after an accidental injection of the pathogen.

Marburg hemorrhagic fever, a virus akin to Ebola, is even deadlier, with mortality ratios as high as 90% in some outbreaks.

Amman has spent much of his career studying Marburg.

Then there are the poxviruses, including Monkeypox virus, first documented in humans in 1970, and Variola virus, the causative agent for smallpox. In the 20th century alone, smallpox killed an estimated 300 million people before it became the first successfully eradicated disease; it exists now only in laboratories but is considered a possible threat for use as a biological weapon.

The CDC Poxvirus and Rabies Branch is one of only two centers in the world authorized by the World Health Organization (WHO) to conduct research on live Variola virus. That work takes place in the CDC's Bio Safety Level 4, or BSL-4 laboratories, so designated because risk group 4 pathogens represent the highest possible danger. Microbes studied in BSL-4 labs pose a significant risk for transmission and are frequently fatal; most have no reliable cure. Thus BSL-4 labs are designed with multiple redundancies to protect laboratory workers and the public while critical research is carried out.

That's where Matt Mauldin works.

Microbiologist Matt Mauldin

Matt Mauldin is a microbiologist in the CDC's Poxvirus and Rabies Branch. His research as both an undergraduate and a graduate student opened the door to a post-doctoral position as an Oak Ridge Institute of Science and Education (ORISE) fellow in the CDC's Poxvirus and Rabies Branch. The job that began by studying the phylogenetics of poxviruses and their hosts now sees Mauldin continuing to research poxvirus genetics, most currently in the genomic comparison of Monkeypox virus isolates in the ongoing human Monkeypox outbreak that emerged in Nigeria in September 2017.

With the emergence of coronavirus 2019-nCoV, Mauldin is volunteering in the CDC's Emergency Operations Center as a data manager for the Person Under Investigation (PUI) Team within the Epi-Task Force. In this role, Mauldin is consolidating and verifying epidemiological data—exposure risks, date of symptom onset, clinical symptoms, etc.—for individuals determined to have met the definition of a Person Under Investigation.

"These data are utilized for analyses to better understand clinical symptoms, incubation periods, and other variables associated with PUIs and confirmed cases, Mauldin says. "Examining these characteristics improves the ability to efficiently identify and monitor individuals who may have been exposed to the virus and reduce its spread."

RELATED NEWS: Follow the latest official updates on 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) from the CDC.

Mauldin also spends a large portion of his time examining the efficacy of third-generation smallpox vaccines through in vitro techniques. His work could be considered a matter of national defense: Mauldin helps develop animal models and in vitro assays for testing medical countermeasures for smallpox and other poxviruses—in the event these pathogens ever are used as a bioterrorism weapon.

"Smallpox is a human-specific disease," Mauldin says, "and these models are imperative for development and testing of medical countermeasures."

Like Brian Amman, Mauldin credits his alma mater for his accomplishments, both on and off the job.

"Not only did Texas Tech prepare me to pursue a career in science, I was also provided a variety of experiences that helped to mold me into a well-rounded person," he says.

For example, serving in TTU's Student Government Association helped Mauldin polish his abilities in communication, collaboration and leadership. A study abroad semester at the Texas Tech Center in Seville, Spain, introduced him to the art and culture of another country, he says, while he advanced in his Spanish language skills.

As a Texas Tech student, Mauldin had an inside track for presenting his research at local, regional and national scientific meetings where he formed relationships with colleagues and mentors across the country.

"Through networking and research opportunities I was able to participate in international field work studies conducted in Mexico, Guatemala and El Salvador," Mauldin remembers.

Bradley (left) instructs Mauldin (second from right) and other students on trapping wood rats for research. Archival photo courtesy Bradley.

Mauldin describes his relationships with people from diverse cultural and educational backgrounds as avenues for personal growth—talking through different viewpoints, finding common ground.

"These skills are important in life, but even more so in public health concerns,"

Mauldin says, "as cultural and economic variables can play important roles in understanding public health problems across the globe."

Since joining the CDC, he has engaged in research and collaboration with individuals in the nations of Colombia, Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, United Kingdom, Germany, Israel, Georgia, India and Singapore on a range of projects. Together, they've identified new viruses, examined virus genetics, tested the efficacy of next-generation smallpox vaccines, and collected small mammals to better understand the natural history of poxviruses—practices that, for Mauldin, had their genesis at Texas Tech.

"Dr. Bradley played a crucial role in developing my scientific thinking, communication and logistics skills," Mauldin says. "His dedication to research and providing a solid scientific foundation for his students was integral in preparing for a career in science."

Like Nowhere Else

Bradley laments the current trend in biology education that focuses on cell and molecular biology to the exclusion of field work.

"A lot of people's view of a porcupine is what it might look like inside of a tube or a picture on the internet. They may not have even seen their research organisms. And so that's one of the things we've done well here is we take kids on field trips. We take them out and show them how to trap rats and show them how to take samples," Bradley says. "And then we take them into the lab and have them do the latest, greatest molecular biology and genomics."

Bradley holds a bat that has been preserved and archived in a storage tray at Texas Tech's Natural Science Research Laboratory.

In addition to field trips, Texas Tech students have access to the cutting-edge resources in the Department of Biological Sciences and the extensive archive of specimens stored at the Natural Science Research Laboratory (NSRL), as well as abundant opportunities to present their findings in scientific meetings.

The combination of advantages given here is what Bradley calls "a perfect storm."

"You know, we're unique because a lot of universities have abandoned organismal biology in favor of more lab-oriented and even biotech, biomedical type research, "Bradley says. "We offer students an experience they might not have at another university."

Bradley (foreground center) and Mauldin (foreground right) organize small aluminum traps on a field trip to sample wood rats. Archival photo courtesy Bradley.

While Bradley has master's and Ph.D. students who have gone on to successful careers as professors, researchers, and administrators at other institutions—and he keeps up with all of them—he's particularly pleased to have five now working at the CDC.

"I am so proud of Brian, Matt, and the other CDC kids. They have grown a tremendous amount as scientists," Bradley says. "All they needed was a chance to succeed, and Tech gave them that. Then, most importantly, they seized those opportunities and ran with them. How cool is that?"

![]()

College of Arts & Sciences

-

Address

Texas Tech University, Box 41034, Lubbock, TX 79409-1034 -

Phone

806.742.3831 -

Email

arts-and-sciences@ttu.edu