PRONGHORN

Antilocapra americana (Ord 1815)

Order Artiodactyla : Family Antilocapridae

DESCRIPTION. A small, deer-like mammal with black, pronged horns that reach beyond the tip of the ears in males; in females they are shorter and seldom pronged; only two toes on each foot (no dewclaws); rump patch, sides, breast, belly, side of jaw, crown, and band across throat white; chin and markings on neck black or dark brown; black patch at angle of jaw in males (absent in females). Dental formula: I 0/3, C 0/1, Pm 3/3, M 3/3 × 2 = 32. Averages for external measurements: of males, total length, 1,470 mm; tail, 135 mm; hind foot, 425 mm; of females, 1,250-135-400 mm. Weight of males, 40–60 kg; females somewhat smaller, averaging about 40 kg.

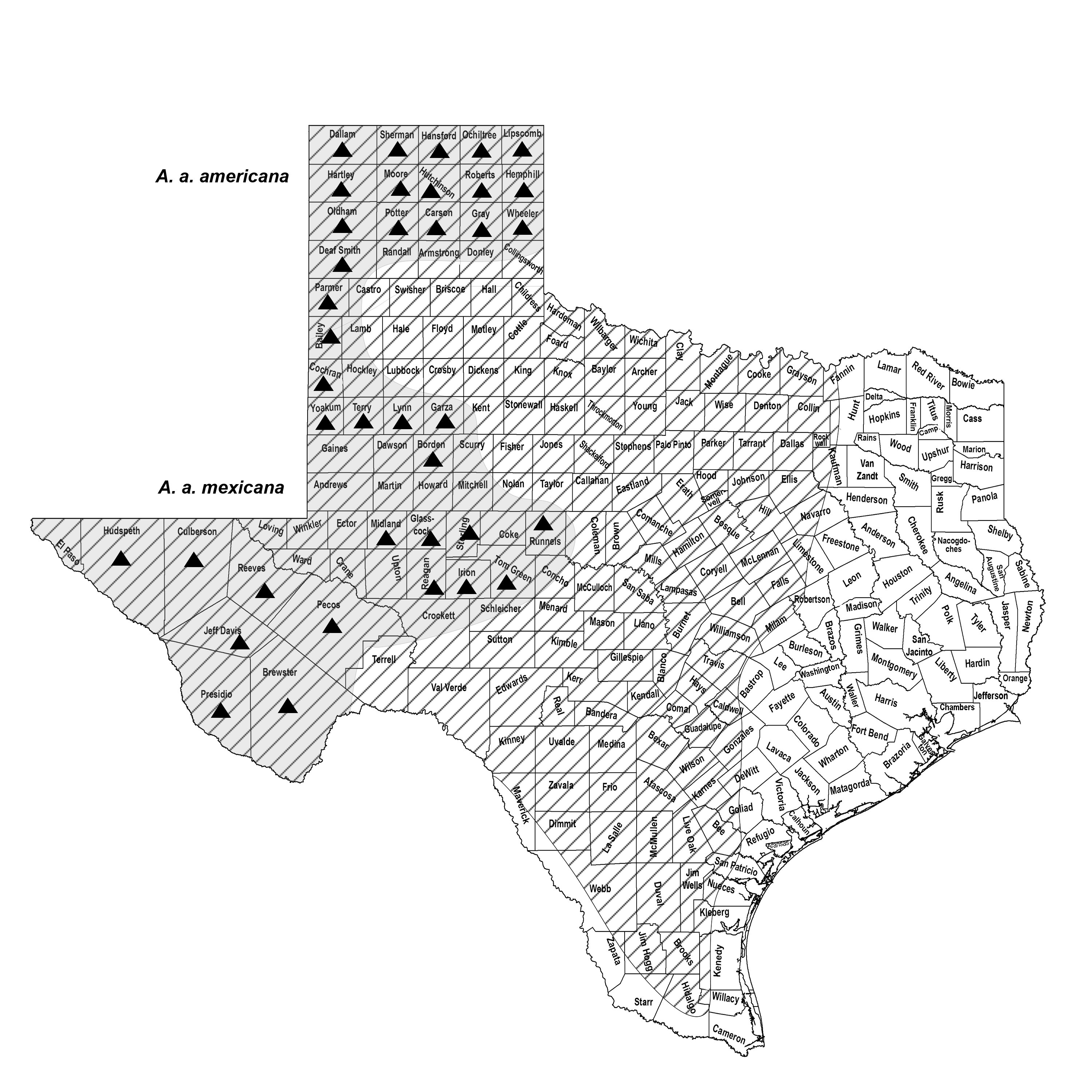

DISTRIBUTION. Formerly distributed over the western two-thirds of Texas, as far eastward as Robertson County in the north and Kenedy County in southern Texas. Now restricted to isolated areas from the Panhandle to the Trans-Pecos, although numbers in the Panhandle appear to be increasing.

SUBSPECIES. Antilocapra a. americana in the Panhandle and A. a. mexicana in western and central Texas, although reintroductions may have altered the subspecies distribution in the state.

HABITS. The fleet-footed, large-eyed pronghorn is an animal of the plains. Adapted for speed and for seeing long distances, it inhabits areas where both its sight and its running will be unimpaired by woodland vegetation. Water in the immediate vicinity is not a requisite because the pronghorn is so adapted physiologically that it can survive for long periods without drinking. Apparently, it has the ability to conserve body water and to produce metabolic water.

Among North American mammals, pronghorns are the most fleet footed. The top speed at which they can run probably does not exceed 70 km (43 mi.) an hour, and certainly it varies with individuals. Most impressive is their endurance; they can run at speeds of 65 km (40 mi.) per hour for about 10 km (6 mi.). An interesting trait of pronghorns is their highly developed sense of curiosity. They insist on examining at close range any unrecognized object, particularly one that is in motion. Because of this, it is possible for a person to lure the animals within close range by hiding behind a bush and waving a handkerchief or other object slowly back and forth. Historically, Native Americans, and sometimes our present-day hunters, have utilized this ruse in bagging them.

Another peculiar trait is their disinclination to jump over fences or other objects. A low brush fence no more than a meter high will ordinarily turn the animals, and small bands have been reduced almost to the point of starvation within a fenced enclosure although plenty of food was available on the outside. They can jump over moderately high obstructions, however, when hard pressed. Ordinarily, they crawl under or between the wires of barbed-wire fences.

Their pattern of daily activity varies considerably with the season, daily weather, and interruptions from predators or human activities. Usually, the animals rise shortly after daybreak and begin a period of intensive feeding lasting 1–3 hours, followed by a period of lying down to rest. Resting for about 1 hour is followed by a long period of feeding through most of the morning. Near midday, another extended period of lying down occurs, succeeded by one or two feeding periods during the afternoon. When the heat of the day is intense in spring and summer, little activity takes place. After about 5 p.m., pronghorns feed steadily until nightfall, at which time they recline for a long period of rest. The alternation of feeding and resting is repeated at night, with longer periods of lying down than during the day.

Pronghorns feed entirely on vegetation, primarily shrubs and forbs. In 1950, Helmut Buechner (Washington State University) found that their summer forage consists of about 62% forbs, 23% browse, and 15% grasses. All parts of the plants were consumed, including leaves, stems, flowers, and fruits.

Pronghorns have a particular fondness for flowers and fruits. The flowers of cutleaf daisy, white daisy, stickleaf, woolly paperflower, and woolly senecio are consumed in large amounts. Although paperflower is poisonous to sheep and woolly senecio is poisonous to cattle, pronghorns apparently suffer no ill effects from either and consume large quantities of both. They do suffer from locoweed (Astragalus mollissimus), although few eat enough of it to die from its poisonous effects.

Autumn forage consists of about 59% forbs, 34% browse, and 7% grasses. More browsing is done in fall than in summer. Winter forage is the same as that in late autumn, with some variation when snow covers the ground, during which time pronghorns consume larger quantities of green woolly senecio; the dried stems and old flower parts of broomweed, stickleaf, and groundswell; old heads of grama grasses; dried leaves of goat weed; and browse species such as javelina bush, Mexican tea, and sacahuista. Little attempt is made to paw away the snow to get the plants. Cedar is used throughout the winter where available in large quantities. Four of the most important winter foods are cutleaf daisy, woolly paperflower, fleabane, and wild buckwheat. In late February, early annuals become available. Early spring flowers, which appear about the middle of March, are eagerly sought. More grass is taken when new green growth appears in spring.

The breeding season of the pronghorn extends from the last week in August to the first week in October. The most vigorous bucks gather small harems of 2–14 does. Young bucks frequently linger at the outskirts of the harem herd and at times attempt to steal a doe or even to interfere with a mature buck in his mating activities. The master of the harem has an endless task in keeping his does together and warding off intruding bucks. The gestation period is 7–7.5 months. The young (usually two) weigh 2–4 kg each and appear in May or June. The female hides her young ones, and at first the fawns are active only a small part of the day. The female goes to them three or more times a day so they can nurse. When about 1 week old, they are able to walk and run well and begin nipping at vegetation. When 1 month old, they graze readily on green vegetation. When the fawns are 1 month to 6 weeks old, does and fawns gather together in small herds that are maintained well into and sometimes throughout the winter season. Nursing continues until the fawns are about 4 months old, so that most of them are weaned about the time of the onset of mating activities.

Sexual maturity is reached at the age of about 1 year in both sexes. There is some indication, however, that young does may breed late in the year in which they are born, as is the case in white-tailed deer. The covering of the horns is shed shortly after the breeding season, beginning about the middle of October and ending in early November. New horn growth is rapid, but the prong is not evident until about the first week in December.

An apparently satisfactory method of judging the age of pronghorns is one also used for domestic sheep. Fawns are born with only two lower incisors and develop four teeth (three incisors and one canine) on each side of the lower jaw by fall. At the age of about 15 months the first middle incisors are being replaced by permanent teeth, at 2.5 years the second incisors are replaced, at 3.5 years the third incisors are replaced, and at about 4 years the pronghorn has a full set of permanent front teeth. After 4 years, age must be judged on the spread of the two middle incisors and the amount of wear on all of the teeth. The life span under natural conditions may be as much as 12–14 years, but the average age attained is probably considerably less.

It is commonly believed that these animals compete seriously with livestock for available forage on the range. According to Buechner, the total amount of competition between cattle and pronghorns is approximately 25%. Competition with sheep is much more severe, reaching at least 40%, as determined by studies in Trans-Pecos Texas. Pronghorns are far more dependent on forbs than are sheep, and where sheep have eliminated those plants on heavily stocked ranges, pronghorns cannot successfully maintain themselves.

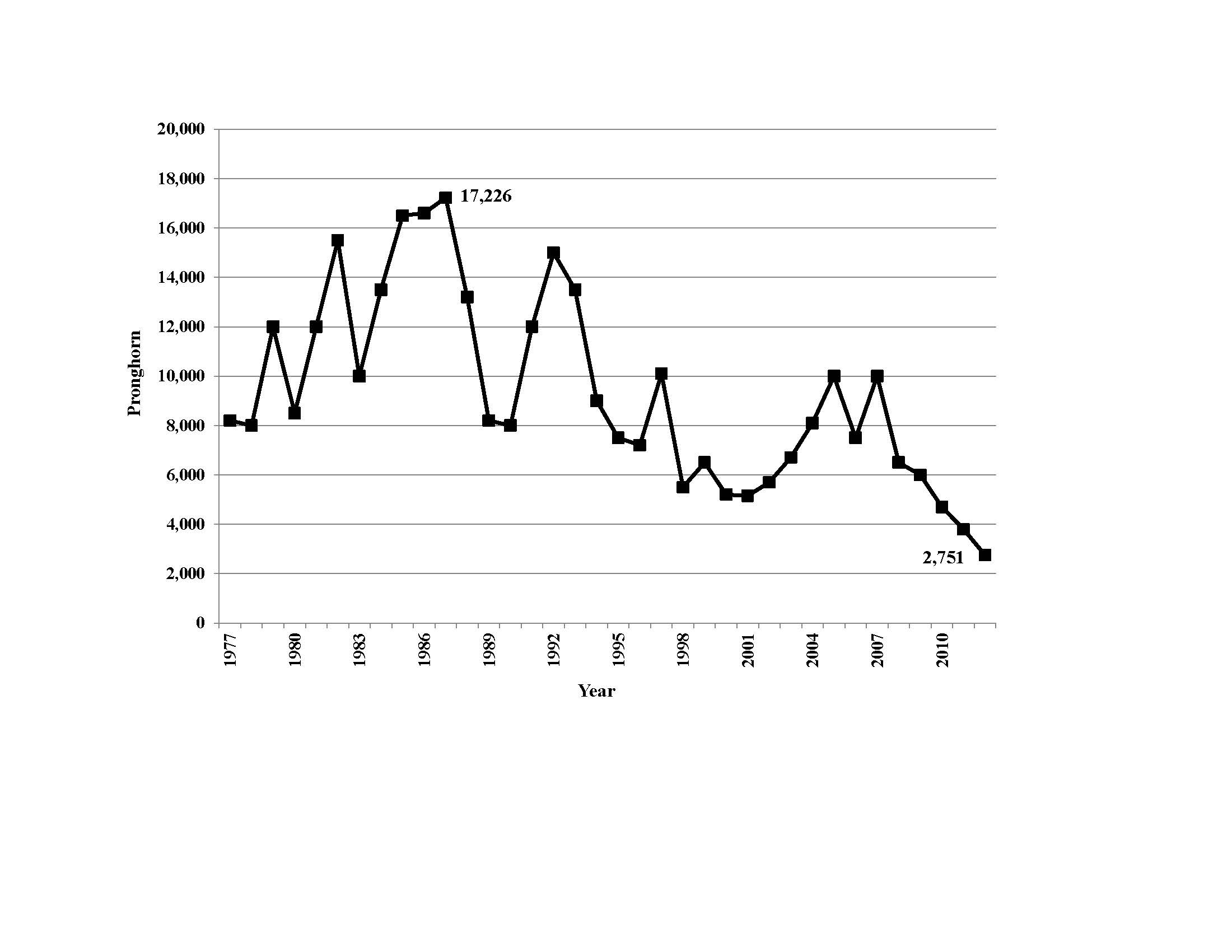

POPULATION STATUS. Uncommon. Pronghorn populations have steadily declined in association with overgrazing of grasslands by domestic livestock, uncontrolled hunting, and extensive cultivation of prairie habitat. It is a desirable game species, but despite extensive management efforts, including restocking programs begun in the 1940s and continuing even today, stable populations have been hard to achieve. This has been especially true in the Trans-Pecos population, which declined from 17,226 animals in 1987 to 2,751 in 2010 (see figure below). The population in the Panhandle region is larger and more stable, and TPWD has begun to transfer animals from there into the Trans-Pecos. As pronghorn numbers have declined, TPWD has reduced hunting permits. Hopefully, these efforts will be successful and populations will begin to recover and stabilize.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the pronghorn as a species of least concern, and it does not appear on the federal or state lists of concerned species. Historically, their decline appears to be associated with drought and predation as well as the human activities of fencing and land use. The statewide population estimate in 2009 was 18,000 animals. The Panhandle supports the largest population, followed by the Trans-Pecos, Rolling Plains, and Edwards Plateau. This is a species that will require serious monitoring and management in the future.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu