Species account of the Mule deer

MULE DEER

Odocoileus hemionus (Rafinesque 1817)

Order Artiodactyla : Family Cervidae

DESCRIPTION. A moderately large deer with large ears; antlers typically dichotomously branched and restricted almost entirely to males; metatarsal gland 8–12 cm long, narrow, and situated above midpoint of shank; upperparts in winter cinnamon buff suffused with blackish, more reddish in summer; brow patch whitish; ear grayish on outside, whitish on inside; tail usually with black tip and white basal portion; underparts white. Dental formula: I 0/3, C 0/1, Pm 3/3, M 3/3 × 2 = 32. Averages for external measurements: of males, total length, 1,755 mm; tail, 152 mm; hind foot, 555 mm; of females, 1,453-175-475 mm. Weight, 57–102 kg.

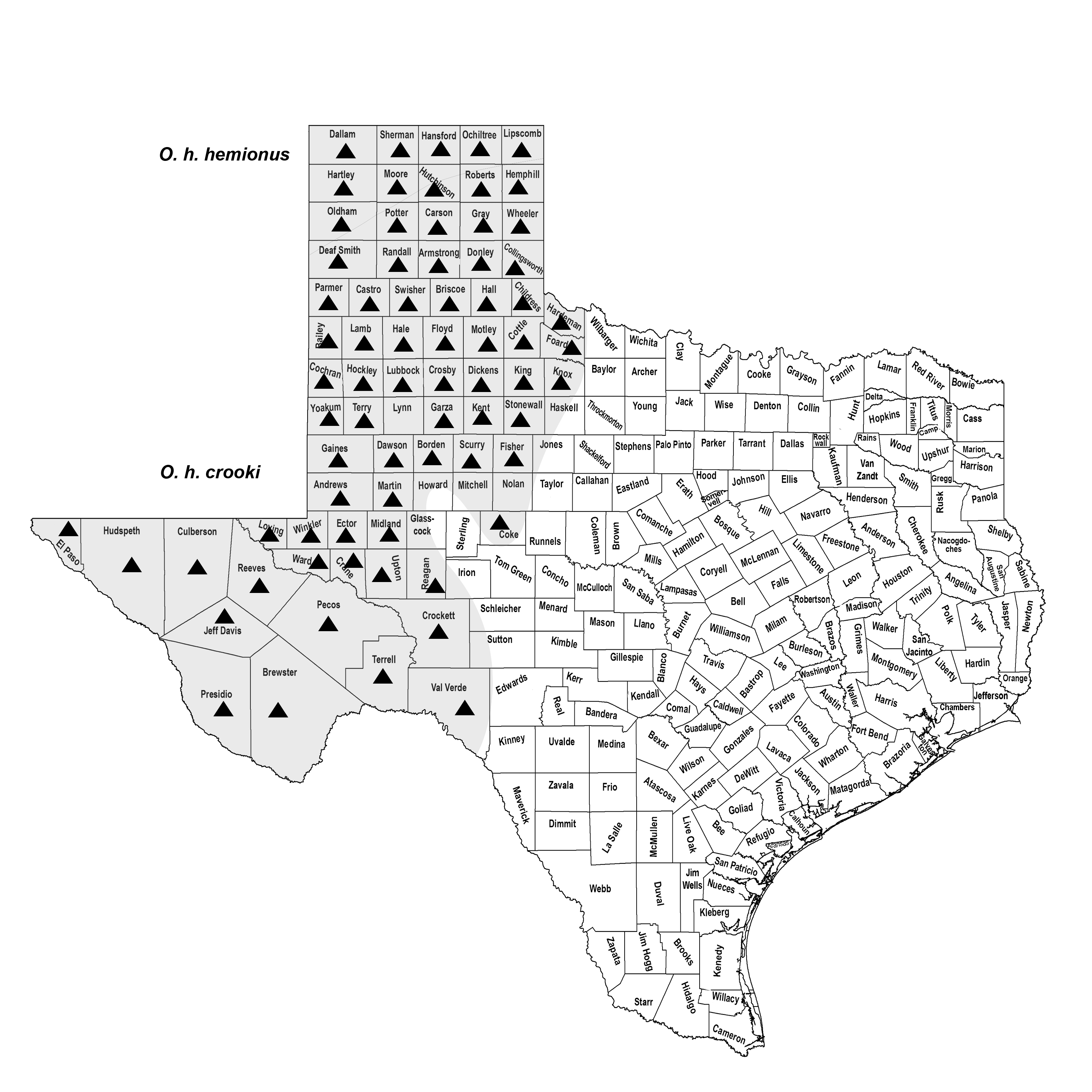

DISTRIBUTION. Occurs over most of the Trans-Pecos and Panhandle regions of Texas and in some areas immediately east of there, partly as a result of introductions. The population size in Texas ranges from about 150,000 during dry conditions to about 250,000 during wetter periods. Approximately 80%–85% of the herd inhabits the Trans-Pecos region, whereas the remainder is found in the Panhandle and western Edwards Plateau regions. The range of the mule deer steadily declined during the past 150 years because of habitat loss and fragmentation and perhaps competition with white-tailed deer. However, their range has expanded in the Panhandle since 1986, and they now occur in almost 90% of the counties there. Deer biologists believe this expansion is related to the adequate cover provided by former crop fields enrolled in the Conservation Reserve Program.

SUBSPECIES. Odocoileus h. crooki in Trans-Pecos and Panhandle; O. h. hemionus in extreme northern Panhandle.

HABITS. Mule deer occupy to some extent almost all types of habitat within their range but, in general, seem to prefer the more arid, open situations in which sagebrush, juniper, pinyon pine, yellow pine, bitter brush, mountain mahogany, and such plants predominate. In western Texas, rocky hillsides covered with lechuguilla, sotol, juniper, and pinyon pine provide the essentials.

The mule deer is noted for its peculiar, high-bouncing gait. Estimates of their speed vary, but Donald McLean (California Fish and Game) was able to force one to a speed of 58 km (36 mi.) an hour on a dry lake flat in California. After the first short burst of speed, the animal reduced its speed to about 35 km (22 mi.) an hour and was badly winded after a chase of <1.5 km (1 mi.). When allowed to choose their own gait, they are able to travel at about 30 km (19 mi.) an hour for a considerable period of time. They are well adapted to rough, broken country, where the long, high bounds send them over the rocks and brush much faster than the average running animal can go through or around the obstructions. The longest bounds are generally made when the animals are going downhill or leaping across gullies. McLean measured two flat jumps, one of 5.9 m (19 ft.) and the other 7.1 m (23 ft.). A downhill bound on a 7% slope measured 8.7 m (29 ft.). They can easily clear a fence 2 m high.

Although equipped with acute senses of sight and hearing, these deer rely largely on the sense of smell in detecting danger. Stationary objects are easily overlooked by them, but they readily detect objects that are in motion.

Mule deer of both sexes normally do most of their feeding in early morning before sunrise or in late afternoon and evening after sundown. They spend the middle of the day bedded down in cool, secluded places. In summer, the bucks retire as soon as the sun shines where they are feeding and go to the dense shade of some grove to bed down for the day. In general, mature bucks prefer rocky ridges for bedding grounds because there they seem to feel more secure from the approach of danger. Does and fawns are more likely to bed down in the open. In winter, however, they often seek out sunny places well screened on at least three sides by vegetation. At night, they usually bed down in the open away from trees and bushes.

The food of the mule deer is quite varied. In the Trans-Pecos, the flowering stalks of lechuguilla, the basal parts of sotol, mesquite, juniper, and a number of forbs contribute to their diet. Feeding time varies with the weather, the phase of the moon, the time of the year, and type of country. During cold, snowy winter months when food is difficult to obtain and a considerable amount is required to maintain body heat and energy, deer feed at all times of day and night. During the rutting season, feeding is often erratic, especially with bucks. During the hunting season, when many hunters are on the range, bucks do the major part of their feeding at night. Deer are more prone to feed on dark nights and are relatively quiet and bedded down when the moonlight is intense. In spring and summer, mule deer tend to feed to a greater extent on green leaves, green herbs, forbs, and grasses than they do on browse species; the reverse is true in fall and winter.

The rut begins in the fall, usually in November or December, but varies with locality and climatic conditions and continues until the latter part of January or even into February. During this period, the bucks have fierce battles in which the antlers are used almost exclusively. Bucks that are evenly matched in size and strength may fight until almost exhausted before one is the victor. The animals are polygamous. The stronger, more virile bucks attract females to them and attempt to defend them against the attentions of the younger bucks. Small, persistent bucks can cause a large buck to lead a miserable life, leaving him little time to eat or rest, because of his continued attempts to drive them away. During the rut, the necks of bucks become swollen, a development that is closely associated with reproduction.

The gestation period is approximately 210 days, and the fawning period extends over several weeks in June–August. The female sequesters herself and births her fawn in a protected locality, where it remains for a period of a week or 10 days before it is strong enough to follow her. At birth, fawns are spotted and weigh approximately 2.5 kg. Young are nursed at regular intervals by the female, 10 minutes of nursing usually sufficing for a full meal. Young are weaned at about the age of 60 to 75 days, at which time they begin to lose their spots. The weaning time is a critical one because if green forage is not available, the fawns seldom make their transfer from milk to a diet of vegetation. If the fawn is not weaned, both mother and fawn are likely to experience difficulty in surviving a severe winter. Sexual maturity is attained at the age of about 18 months in does, but ordinarily young do not participate actively in the rut until they are 3 or 4 years old.

Antlers are shed after the breeding season, from mid-January to about mid-April. Most mature bucks in good condition have lost theirs by the end of February; immature bucks generally lose them a little later. New antler growth begins immediately following the shedding of the old. Growth is extremely rapid, and massive antlers develop fully in about 150 days. While the antlers are growing, the bucks remain on the open slopes and benches where the brush is short or scattered to avoid injuring the soft, new growth. Mature bucks normally have four main points on each antler, but beyond the third year there is little or no correlation between the number of points and the age of the deer. Beyond the prime of life, the so-called Pacific buck type may develop, which consists of only two points, or a spike, on each side of a large set of antlers.

The age of mule deer can be determined fairly accurately up to about 24 months. At birth, the fawn is equipped with upper premolars, the third and fourth lower premolars, the lower canines, and the entire lower incisor series. The second lower premolar may erupt shortly after birth or within the first 60 days. By the age of 3.5 months, the first upper molar is functional. At the age of approximately 1 year, the middle lower incisor is shed and replaced by a permanent one. Each permanent incisor is wider than its predecessor. At the age of 15–18 months, the molars erupt and take their place in the series, and at the age of 24–25 months, the premolars are replaced by the permanent dentition.

There is some competition between mule deer and livestock on the range, particularly in spring and early summer. Furthermore, diseases such as hoof-and-mouth disease can be transmitted from mule (and white-tailed) deer to livestock, and vice versa, so that once the disease is established in wild animals drastic measures must be taken to curb it. Anthrax is also said to be propagated and spread by deer, and these animals are also capable of harboring the causative agents of tularemia or rabbit fever. Chronic waste syndrome is a recent concern in deer populations.

POPULATION STATUS. Common. Mule deer are of considerable economic importance as a big game animal, but their populations are considerably lower and thus of more concern than those of white-tailed deer (O. virginianus). There are indications that hybridization with or replacement by white-tailed deer, or both, is occurring in some regions. In several studies, sympatric populations of mule deer and white-tailed deer in western Texas have been found to interbreed and produce hybrid offspring. Genetic analyses indicate that these hybrids are more characteristic of white-tailed deer than of mule deer; thus, it appears that hybridization may be one factor contributing to the displacement of mule deer by white-tailed deer in this region.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the mule deer as a species of least concern, and it does not appear on any federal or state lists of concerned species. Long-term drought conditions in the Trans-Pecos region also appear to be pushing mule deer populations downward. The Panhandle population, however, has been increasing in both numbers and distribution. This is a species that bears special monitoring in the twenty-first century.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu