Species account of the Hog-nosed Skunk

HOG-NOSED SKUNK

Conepatus leuconotus (Lichtenstein 1832)

Order Carnivora : Family Mephitidae

DESCRIPTION. Largest of the North American skunks; a single, broad white stripe from top of head to base of tail; long, bushy tail white all over with a few scattered black hairs beneath; rest of body blackish brown or black; white stripe on head truncate or wedge shaped; snout relatively long, the naked pad about 20 mm broad and 25 mm long; nostrils ventral in position, opening downward; ears and eyes small; five toes on each foot; claws of forefeet much larger than on rear feet, strong and adapted for digging; pelage relatively long and coarse; underfur thin. Young colored like adults; sexes alike in coloration. Dental formula: I 3/3, C 1/1, Pm 2/3, M 1/2 × 2 = 32. Averages for external measurements: of males, total length, 577 mm; tail, 248 mm; hind foot, 65 mm; of females, 542-202-68 mm. Weight, 1.1–2.7 kg, rarely to 4.5 kg. Females are smaller than males.

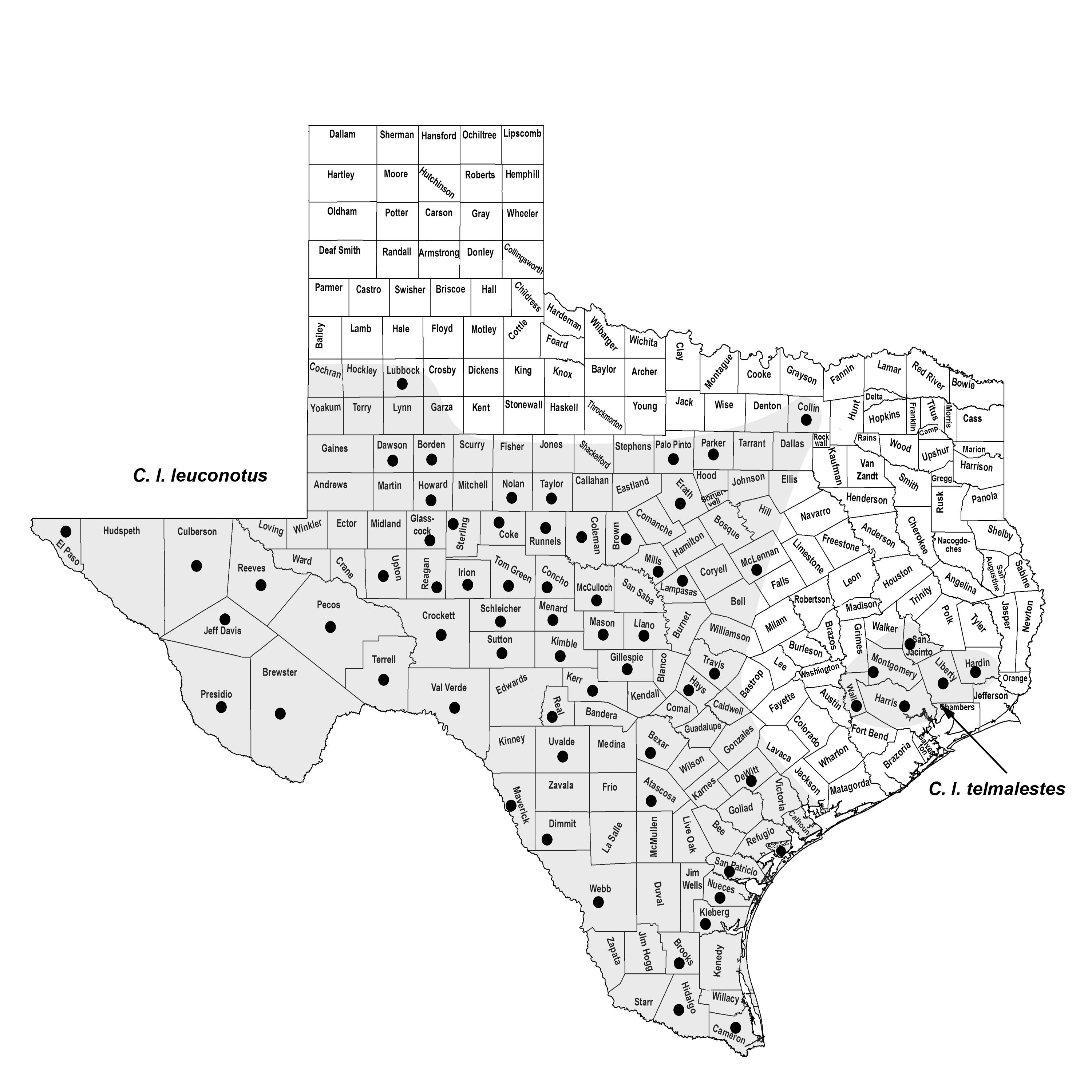

DISTRIBUTION. Occurs throughout southern and central Texas, north at least to Collin and Lubbock counties. Recent specimens in the Rio Grande Valley (Willacy County) indicate a viable population in that region. A former isolated population in the Big Thicket region of eastern Texas has been extirpated.

SUBSPECIES. Conepatus l. leuconotus throughout most of the range in the state and C. l. telmalestes (presumably now extinct) from the Big Thicket region.

HABITS. These white-backed skunks inhabit mainly the foothills and partly timbered or brushy sections of their general range. They usually avoid hot desert areas and heavy stands of timber. The largest populations occur in rocky, sparsely timbered areas such as the Edwards Plateau of central Texas and the Chisos, Davis, and Guadalupe Mountains of Trans-Pecos Texas. In South Texas, they have been collected or observed in several habitat types, including live oak brush, mesquite brushland, and improved pasture within semi-open native grassland. Their presence in an area usually can be detected by the characteristically plowed-looking patches of ground where the skunks have rooted and overturned rocks and bits of debris in their search for food. Their hog-like habit of rooting has led to the adoption of the term "rooter skunk."

Generally, hog-nosed skunks are nocturnal; however, in midwinter in central Texas, they prefer to feed during the middle of the day. They seldom are as abundant in any part of their range as the striped skunk, Mephitis mephitis. Like other skunks, they are relatively unafraid of humans or other animals and do not hesitate to defend themselves with their powerful musk if disturbed. In the Guadalupe Mountains of western Texas, William B. Davis (Texas A&M University) watched one at close range at night with a flashlight for nearly 30 minutes as it rooted about in search of food. When approached too closely, fair warning is given as the skunk elevates its tail and maneuvers to place the observer in the line of fire.

Hog-nosed skunks prefer rocky situations when available because the numerous cracks and hollows can serve as den sites. Not only do they winter in such dens, but they also use them as nurseries. Unlike the striped skunk, this species is more or less asocial. Usually only one individual lives in a den, but a trapper in central Texas reported that he once found a winter den occupied by two individuals.

Their food habits make them valuable assets in most areas. Based on analysis of stomachs and other viscera of 83 individuals from central Texas, their seasonal food (expressed in percentages) consists of, in fall, insects (52), arachnids (4), vegetation (38), and reptiles (6); in winter, insects (76), arachnids (12), small mammals (9), and vegetation (3), with reptiles and mollusks making up the balance; in spring, insects (82), arachnids (12), and reptiles (6); and in summer, insects (50), arachnids (9), small mammals (3), vegetation (31), snails (5), and reptiles (2).

The breeding season begins in February, and most females of breeding age are with young in March. The female has only 6 teats (as opposed to 12–14 in the striped skunk), suggesting small litters of young. In the 1970s, Robert Patton found that females generally produce two litters, each consisting of three individuals. Rancher J. D. Bankston of Mason, Texas, reported that he had never seen more than four young with a female. The young are born in late April or early May. The gestation period is approximately 2 months. Little has been recorded on the growth and development of the young, but we do know that they can crawl about in the nest before their eyes are open and that at that tender age they can emit a drop or two of musk. By the middle of June they are about the size of kittens and weigh about 450 g. Most young are weaned by August.

POPULATION STATUS. Uncommon. Hog-nosed skunks have disappeared from the Big Thicket and from much of the South Texas Plains region. Although they are still considered common in the central part of the state, especially in the Hill Country, there is a growing consensus among professional mammalogists that the overall population level of hog-nosed skunks in Texas has declined drastically during the past few decades.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the hog-nosed skunk as a species of least concern, although it reports

this species as declining throughout its range. It does not appear on the federal

or state lists of concerned species. Relatively little is known about the ecology

and behavior of these animals, and the reasons for their decline are unknown at this

time. Several possible explanations that have been proposed include the conversion

of brushy habitats to row-crop agriculture, competition with feral pigs, and the use

of pesticides that may limit the insect food source for the skunks.

Recently, Michael Tewes (Texas A&M–Kingsville) obtained a specimen of hog-nosed skunk

in Willacy County and reports seeing others on somewhat rare occasions. These observations

indicate that, although extremely rare, hog-nosed skunks do exist in South Texas.

This species will require careful monitoring in the future.

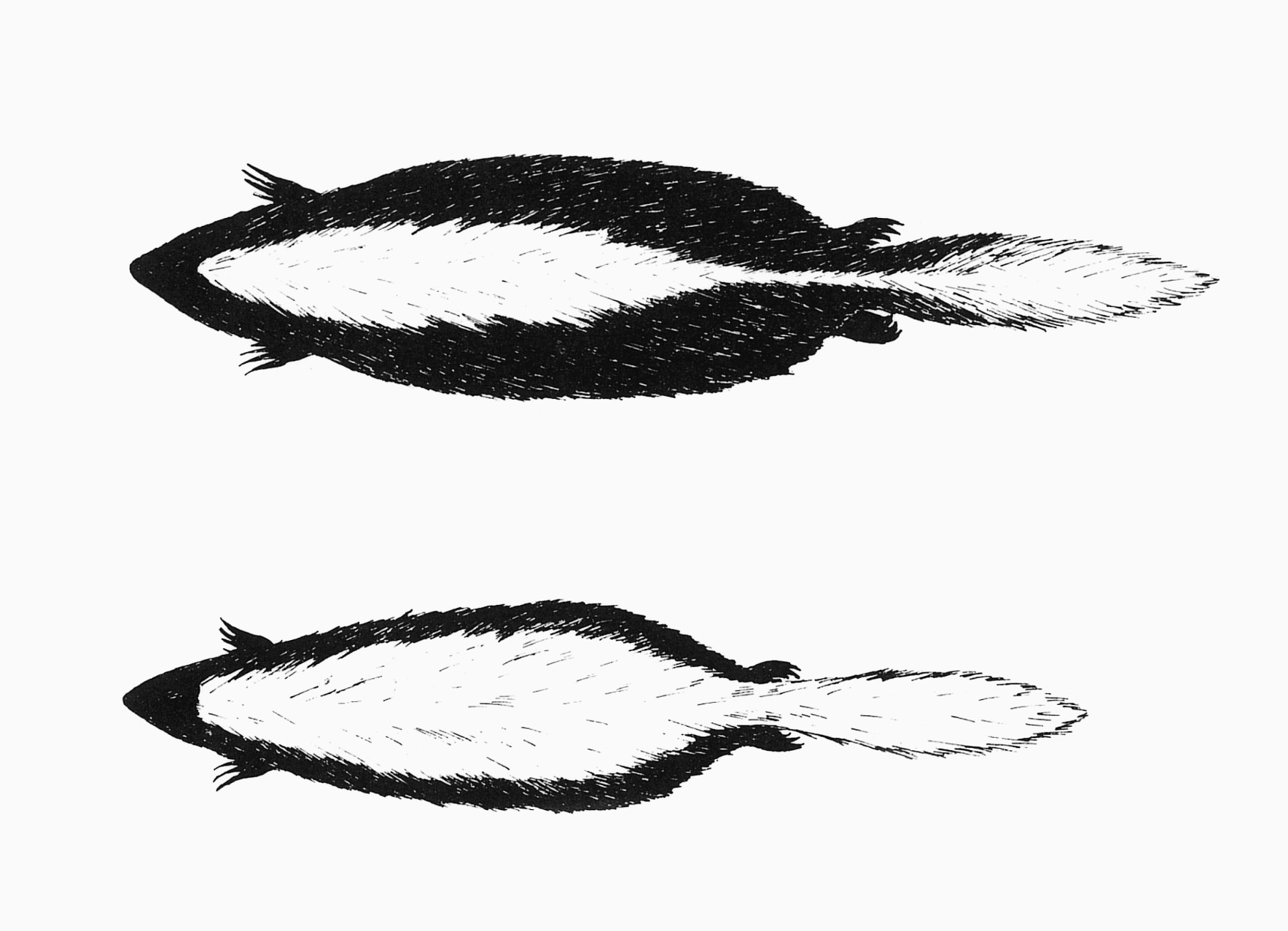

REMARKS. The hog-nosed skunks of Texas were formerly treated as two species, Conepatus leuconotus and C. mesoleucus. In 2003, Jerry Dragoo and colleagues (Texas A&M University) combined the two as one species based on morphological and genetic analyses. There are, however, differences in the color pattern of the two forms (see figure below). The western form (formerly C. mesoleucus) has one broad stripe running from the top of the head to the base of the tail. The tail is long, bushy, and white all over except for a few scattered hairs underneath. The Gulf Coast form (formerly C. leuconotus) resembles the western form, but it is larger and the white stripe on the back is much narrower, wedge shaped rather than truncate on the head, and reduced in width or entirely absent on the rump. The upper side of the tail is white, but the underside is black toward the basal half and white toward the tip.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu