Species account of the Black-footed Ferret

BLACK-FOOTED FERRET

Mustela nigripes (Audubon and Bachman 1851)

Order Carnivora : Family Mustelidae

DESCRIPTION. A large version of the common long-tailed weasel; upperparts pale buffy yellow, overcast with brown hairs on head and back; underparts buffy or cream colored; feet and tip of tail blackish; broad black mask across face and eyes. Dental formula: I 3/3, C 1/1, Pm 3/3, M 1/2 × 2 = 34. Averages of external measurements: of males, total length, 570 mm; tail, 133 mm; hind foot, 60 mm; of females, 500-120-55 mm. Weight, probably 850–1,400 g in males, 450–850 g in females.

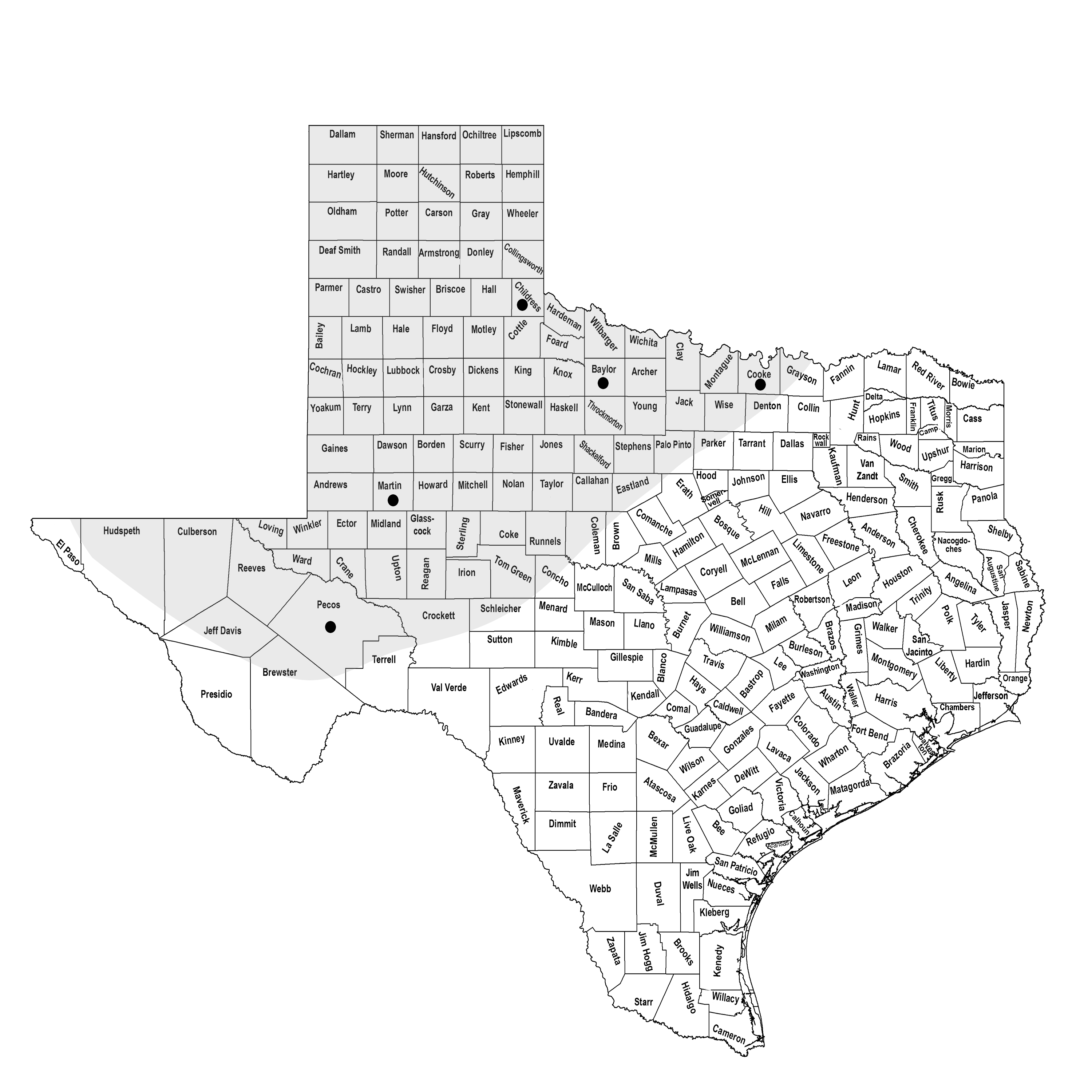

DISTRIBUTION. Originally the same as that of the black-tailed prairie dog, roughly the northwestern third of Texas including the Panhandle, much of the Trans-Pecos, and a considerable part of the Rolling Plains east and southeast of those areas. Now extirpated from Texas. The last Texas records were from Dallam County (1953) and Bailey County (1963).

SUBSPECIES. Monotypic species.

HABITS. Black-footed ferrets are associated primarily with prairie dogs and prairie dog towns. Although individuals have been seen under haystacks, in alfalfa fields, and in buildings, most of these sightings were made during the fall dispersal of the young. Historically, the range of the ferret coincided closely with that of the various species of prairie dogs, which is the primary food source. In addition, prairie dog burrows provide the ferrets with shelter and nursery sites for rearing their young.

Both the young and the adults are primarily nocturnal. Young ferrets rarely appear above ground during daylight hours until about mid-August. Adults, however, occasionally leave their burrows during the day to sunbathe or to forage. When a ferret is active in daylight, the prairie dogs stay above ground, keeping the intruder under surveillance, and appear to be highly nervous and agitated. This behavior of the prairie dogs is a reliable clue that a ferret is present in the dog town. A better clue, however, is the presence of a peculiar shallow trench leading from a prairie dog burrow. When a ferret alters a prairie dog burrow or digs one of its own, it backs out with the dirt held against its chest and drags the dirt farther from the burrow entrance each time. The result is a trench 8–12 cm wide and up to 3.5 m long. These trenches are formed mostly at night and, if fresh, are a sure sign of the presence of a ferret. No other species of animal living in a dog town leaves this type of structure.

The mainstay of black-footed ferrets is prairie dogs, which the ferrets capture and kill in their burrows at night. Analyses of 56 scats revealed that remains of prairie dogs occurred in 51 of them and constituted 82% of the identifiable animal material. Mouse remains occurred in 19 scats and made up the remaining 18%. Ferrets also have been seen chasing birds and catching moths. Determining their food habits by scat analyses can become quite a chore because the ferrets deposit most of their feces in the burrows they occupy. Only a few scats have ever been found aboveground by investigators diligently searching for them.

Mating is believed to occur in April or May. One female killed on 16 May appeared to be in estrous; a female trapped on 3 May was pregnant; a nursing female was captured on 20 June. The female alone cares for her litter of four or five young, even though the male may stay in the same prairie dog town. As soon as the young are able to travel, the female coaxes them out of the nest burrow and leads them as she carefully checks several other burrows, finally selecting one for her litter and a separate one for herself. As they grow older, the young follow their mother, and from June to mid-July they travel with the female as she hunts. By mid-July the young are half grown and readily eat prey that the female kills.

By early September the young are nearly full grown and begin to disperse from their birthplace. It is during the period of dispersal that the young are exposed to the greatest mortality. More than 40% of the dead ferrets found outside prairie dog towns were recorded from mid-August to mid-October. Ferrets do not hibernate, and during late fall, winter, and spring they are usually found singly.

POPULATION STATUS. Extinct. Once numerous in prairie dog towns across the state, the black-footed ferret was driven to extinction in Texas with the demise of prairie dog populations and the occurrence of sylvatic plague.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN and USFWS lists the black-footed ferret as endangered but increasing in numbers due to reintroductions. It is not listed by TPWD based on the status "extinct in the wild."

REMARKS. In 1979 the species was thought to be extinct in the wild throughout its range. In 1984, however, one surviving colony, numbering about 130 individuals, was discovered at Meteetsee, Wyoming. That colony subsequently suffered an epidemic of canine distemper. In 1986 the remaining 18 ferrets known to have survived were captured and put into a captive breeding program. In the fall of 1991 the first group of captive-born ferrets was released in the Shirley Basin area of Wyoming. An additional 83 captive-born ferrets were released in Shirley Basin during the fall of 1992. These initial attempts at reintroduction met with limited success, but in the last few decades much has been learned about the successful breeding of ferrets as well as their ecology, and reintroduction efforts are meeting with more success. Approximately 150–220 ferrets are released to the wild each year. Today, there are an estimated 1,000 ferrets living in the wild at sites in Wyoming, South Dakota, Arizona, Kansas, New Mexico, Montana, and Canada. Although the captive breeding and reintroduction capabilities continue to improve, habitat availability and stable prairie dog towns remain a limiting factor in the effort to restore this species to the North American landscape. Discussions are underway to attempt a reintroduction in Texas.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu