Species account of the Japanese macaque

JAPANESE MACAQUE*

Macaca fuscata Blyth (1875)

Order Primates : Family Cercopithecidae

(Introduced species)

DESCRIPTION. Japanese macaques, also known as snow monkeys, range in color from shades of brown and gray to yellowish brown. They have a hairless, colorful face and posterior end that are pinkish red in color. Their fur is very thick, which helps them survive during harsh winters. They have a short, stumpy tail; large eyes; and big ears. They also have very long fingers with sharp nails at the tip. They are sexually dimorphic, with males taller and more massive than females. Males average 11.3 kg in weight and 57 cm in height; females average 8.4 kg and 52.3 cm in height.

DISTRIBUTION. Japanese macaques inhabit subtropical to subalpine deciduous broadleaf and evergreen forests on three of the southern main islands of Japan (Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu) as well as a few smaller islands. They also survive well outside their natural range, including an introduced population in southern Texas.

SUBSPECIES. Two subspecies are known, M. f. fuscata and M. f. yuakui. The former is the mainland subspecies and was the one brought to Texas; the latter subspecies is restricted to the island of Yakushima.

HABITS. Macaques mostly move on all fours. They are semiterrestrial, with females spending more time in trees and males spending more time on the ground. They are known for their leaping and swimming ability. Macaques live an average of 6.3 years but males are known to live as long as 28 years and females up to 32. They live in matrilineal societies, and females stay in their natal groups for life; males move out before they are sexually mature. Males within a group have a dominance hierarchy, with one male having alpha status. The dominance status of males usually changes when a former alpha male leaves or dies. Females also exist in a stable dominance hierarchy, with a female's rank depending on her mother.

Males and females form a pair bond and mate, feed, rest, and travel together, and this typically lasts 1.6 days during the mating season. Females enter into courtship with an average of four males a season. During the mating season, the face and genitalia of males redden and the tail will stand erect. Females' faces and anogenital regions turn scarlet. Macaques will copulate both on the ground and in the trees. After a gestation period of 173 days, females bear only one young weighing about 500 g. A female carries her baby on her belly for the first 4 weeks after birth. After this time, the mother transports the infant on her back. A mother and her infant tend to avoid other troop members.

The Japanese macaque is omnivorous and will eat a variety of foods, including plants, insects, bark, fungi, ferns, fruit, and nuts. When food items are scarce, macaques will dig up underground plant parts (roots or rhizomes) or eat soil and fish. These animals are thought to be very intelligent.

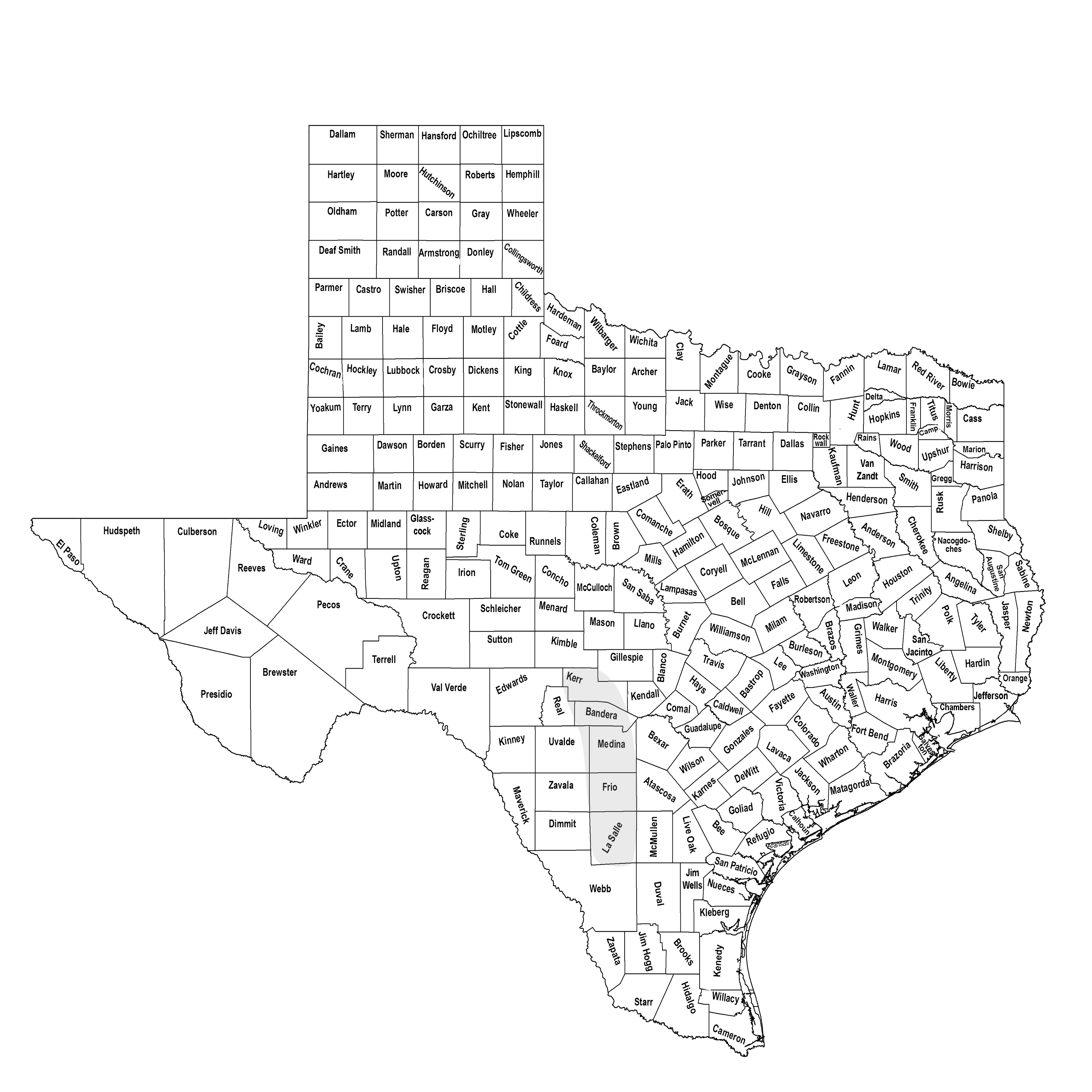

POPULATION STATUS. Introduced; feral. The history of the Japanese snow monkey and how it came to Texas is fascinating. The monkeys are descendants of a small troop brought here in 1972 to save them from destruction in Kyoto, Japan, where they had become regarded as a pest. The initial troop, which included about 150 animals, was brought to a ranch near Encinal, La Salle County, where the monkeys remained until 1980, when they became the property of the South Texas Primate Observatory, were confined for behavioral research, and moved to a ranch near Dilley, Frio County. The observatory was in an enclosed ranch-style environment, and animals were allowed to roam with minimum human interference.

At first many of the monkeys perished in the unfamiliar arid brushland habitat, but the macaques eventually adapted to the environment and learned to forage for mesquite beans, cactus fruits, and other foods. By the late 1980s, the population had increased from the original 150 animals to between 500 and 600 individuals. Because of a lack of funding, the monkeys' enclosure fell into disrepair and several escaped. The troop was not enclosed within any physical barriers and ranged over an area of approximately 100 ha (250 acres) of ranchland, foraging extensively on native vegetation and enhanced with a daily provision of monkey chow and grain.

The monkeys took advantage of fabricated perches, row crops, and food provided to them as well as feed pilfered from local farms and ranches. They learned to defeat fences, locks, and gates. Much like farm animals, they became semidependent on the proximity of humans. People began to call authorities and complain about them running around the countryside outside the observatory and damaging property. A bobcat or cougar apparently killed the troop's leader, which stressed the troop, but the population continued to sustain between 500 and 600 individuals. The troop had to be relocated on two more occasions until it finally ended up on another site in Dilley that became known as the Texas Snow Monkey Sanctuary.

In 1996 hunters maimed or killed four escaped macaques, which caused a public outcry; shortly afterwards, legal restrictions were publicly clarified and funds were raised to establish a new 75 ha (185 acre) sanctuary near Dilley, Frio County, Texas. The monkeys now live in an electrified enclosure where they can swim in water tanks, forage through the vegetation, sleep in trees, and live as free individuals with a sound social unit. In 1999, the Animal Protection Institute took over the management of the Texas Snow Monkey Sanctuary. Since that time the sanctuary has expanded to become a haven for rescued monkeys of all types. Today the site near Dilley is called the Born Free USA Primate Sanctuary. In addition to the group of snow monkeys that are descendants of the Japanese arrivals, the sanctuary provides refuge for other snow monkeys, other species of macaques, and baboons that were all rescued from roadside zoos, research laboratories, and private possession and had lived most of their lives in cages.

CONSERVATION STATUS. Today the IUCN lists the Japanese macaque as least concern with a stable population. According to the IUCN, the species has a large global population and is not experiencing any serious declines, although some local populations are under threat by deforestation and hunting because they are agricultural pests. In 1976 the US federal government listed the monkeys as threatened, but in 1994 the USFWS ruled that the Dilley troop of macaques was not a protected species. At least initially the TPWD agreed, saying there was nothing in state or federal law forbidding the shooting of feral macaques because they were classified as an "exotic unprotected species." Almost simultaneously, the US Department of Agriculture began pressuring the volunteer observatory managers to improve the Dilley facility, citing violations ranging from inadequate housing to failure to construct a secure perimeter fence. On the final day of the 1995–1996 hunting season, after the four snow monkeys were shot, public sentiment led entertainer Wayne Newton to host a fundraiser in San Antonio for the monkeys. People gave cash and their time, and shortly after the shootings, the snow monkeys were moved to the larger and more secure facility near Dilley where they live today. Also, TPWD clarified the legal status of refuge primates. Now, there is no monkey hunting in Texas, and you cannot shoot a trespassing monkey.

REMARKS. A book was published in 1993 by S. M. Pavelka about the Japanese snow monkeys in Texas (see appendix 3). Also, there have been sightings of snow monkeys in locations in Texas far away from Dilley. In May 1998 a group of mammalogy students under the direction of one of us (RDB) encountered a Japanese snow monkey about 16 km (10 mi.) west of the Kerr Wildlife Management area in Kerr County, which is approximately 240 km (150 mi.) north of Dilley. The monkey crossed the road in front of their vehicle and scrambled into the lower limbs of some nearby mesquite trees. Some of the students in the class pursued the monkey over a 100 m (328 ft.) area through the mesquite and oak mottes before it quickly outdistanced them. It was not known whether this individual macaque represented a released pet or if it was part of a feral population, but given its behavior and "wildness," it did not appear to be a pet.

Japanese macaques are considered to be a nuisance, and where they occur in Japan they are the third worst crop pest behind wild boar and deer. They are also easily habituated to humans and may not be easily scared away. They carry similar diseases to humans, which is probably the biggest concern about their establishment in the wild outside their native range.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu