BLACK-TAILED PRAIRIE DOG

Cynomys ludovicianus (Ord 1815)

Order Rodentia : Family Sciuridae

DESCRIPTION. A large, robust, ground-dwelling squirrel with upperparts pinkish cinnamon mixed with buff; tail sparsely haired, tipped with black, and about one-fifth of total length; eyes large; ears short and rounded. Dental formula: I 1/1, C 0/0, Pm 2/1, M 3/3 × 2 = 22. Averages for external measurements: total length, 388 mm; tail, 86 mm; hind foot, 62 mm. Weight, 1–2 kg.

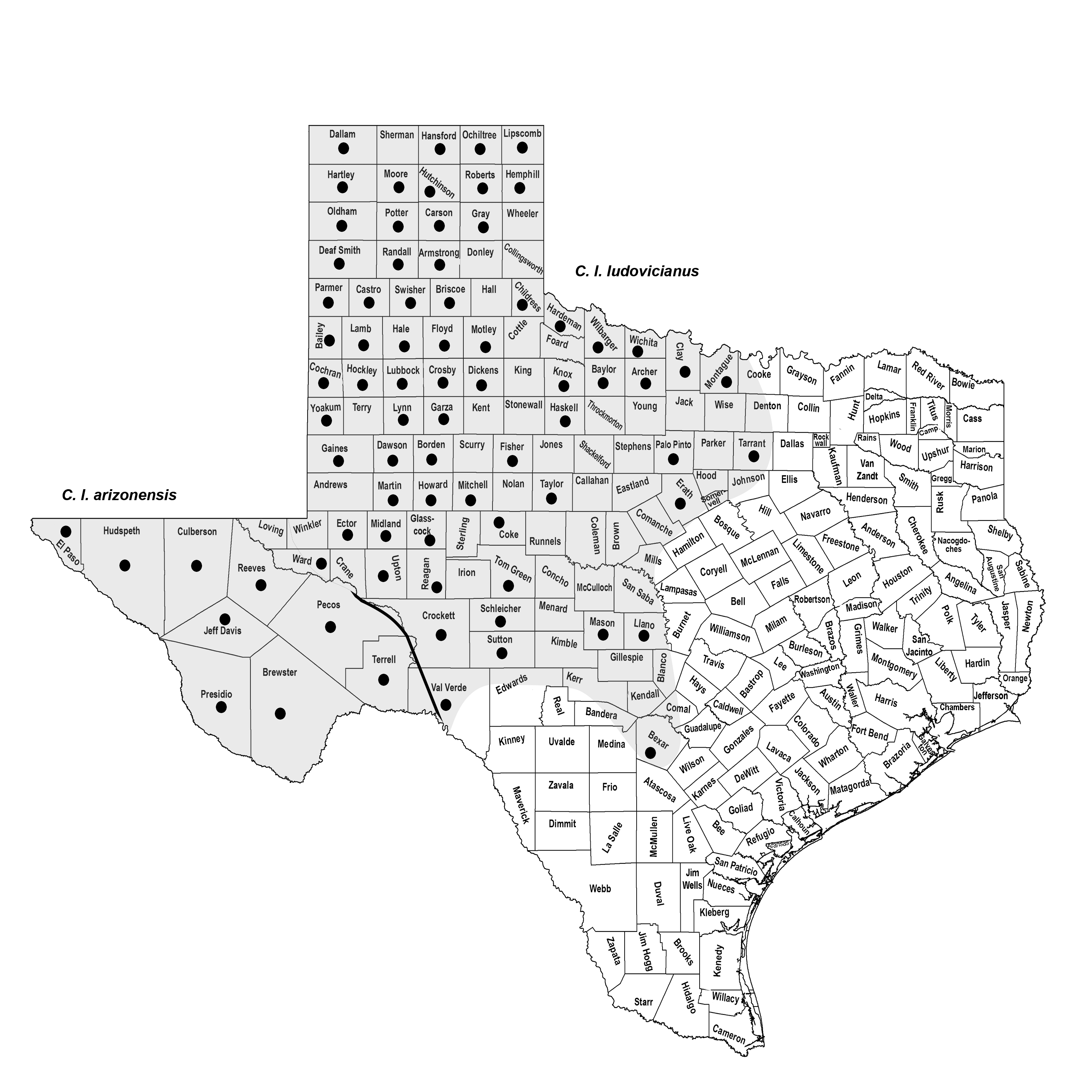

DISTRIBUTION. Once occurred in western half of state from north of Rio Grande Plains; easternmost records from Montague and Tarrant counties in north and Bexar County in south; now extirpated over much of its former range.

SUBSPECIES. Cynomys l. arizonensis in the Trans-Pecos and C. l. ludovicianus elsewhere.

HABITS. Black-tailed prairie dogs typically inhabit short-grass prairies; they usually avoid areas of heavy brush and tall grass, possibly because visibility is considerably reduced. In the Trans-Pecos region, favored habitat sites are alluvial fans at the mouths of draws, hardpan flats where brush is sparse or absent, and the edges of shallow valleys. Overgrazed or denuded pastureland also provides good habitat for C. ludovicianus.

The term prairie dog is an unfortunate misnomer because the animal is not even remotely related to a dog. It is a ground squirrel with a superficial resemblance to a small, fat puppy; in addition, they emit a warning call that resembles a barking sound. These squirrels are sociable creatures and live in colonies, or towns, that may vary in size from a few individuals to several thousand animals. During the biological survey of Texas, Vernon Bailey recorded that at the end of the nineteenth century an almost continuous and thickly inhabited dog town extended in a strip approximately 160 km wide and 400 km long (100 × 250 mi.) on the high plains of Texas. This city had an estimated population of 400 million prairie dogs. Such large concentrations are now a thing of the past due to extensive removal efforts and the conversion of land for agriculture.

Their dens consist of deep burrows 7–10 cm in diameter. The entrances are funnel shaped and usually descend at a steep angle for 2–5 m before leveling off. One described burrow dropped nearly vertically for 4.5 m, then turned abruptly and became horizontal for 4 m. Blind side tunnels and nest chambers extended from the lower part. The main entrances are marked by the mounds and parapets constructed around them. These crater-like dikes are often 30 cm or more in height and doubtless serve to keep flash floods from inundating the burrows and also as lookout points.

Black-tailed prairie dogs are strictly diurnal and are most active in the morning and evening periods. The midday hours are usually spent sleeping below ground. In summer, they store up reserves of fat to support them during the winter months. In the northern part of Texas, they begin hibernating in November. Hibernation seems to be less complete in prairie dogs than in true ground squirrels. Prairie dogs often hibernate during exceptionally cold weather, then become active again as the weather warms.

Their food is mainly plant materials, particularly low-growing weeds and grasses. In the Trans-Pecos region, burrograss and purple needlegrass are especially favored foods. Their year-round diet as determined by one investigator is as follows: grasses (61.6%), goosefoot family (12.7%), mustard family (4.5%), prickly pear (6.0%), and other plants (13.9%). Insects, especially cutworms, accounted for only 1.4% of the total diet. They are voracious eaters. According to C. Hart Merriam, 32 prairie dogs consume as much food per day as one sheep, and 256 eat as much as one cow.

Prairie dogs are highly gregarious and populations comprise several small coteries, or harems, of two to eight females that are defended by a single dominant male. In turn, coteries are organized into larger population units called wards, which are separated by unoccupied areas of unsuitable habitat or other such barriers. Activity and breeding are usually conducted within the coteries; however, dispersal between coteries and wards occasionally occurs, usually by young males. This complex social structure is thought to contribute to increased genetic variability between both coteries and wards.

A single litter of young is produced annually in March and April. Litter size is usually 4–5 young, but as many as 10 young have been reported in a litter. At birth, the pups are blind and hairless and weigh about 15 g. At 13 days fine hair covers the cheeks, nose, and parts of the body; the weight is then about 40 g. At 26 days, the body is well haired and they can crawl awkwardly. Their eyes open at the age of 33–37 days, at which time the young prairie dogs are able to walk, run, eat green food, and bark. They first appear aboveground when about 6 weeks of age and are weaned shortly after that. The family unit remains intact for almost another month, but the ties are gradually broken, and the family disperses. Sexual maturity is reached in the second year.

These squirrels have been displaced by livestock and farming interests for the past century. Consequently, their former range and numbers have been considerably reduced. Large concentrations of prairie dogs can damage cultivated crops or compete with livestock, but the desirability of eliminating them entirely from rangelands has not been satisfactorily justified. Ranchers in certain parts of Texas, for example, claim that removal of prairie dogs has had some direct association with the undesirable spread of brush. This has had detrimental effects on the livestock industry that far outweigh the damage prairie dogs might do.

POPULATION STATUS. Uncommon to common. The current status of the black-tailed prairie dog in Texas has been a controversial issue in recent years. In some places it is quite common; however, many prairie dog towns have been eliminated. It is estimated that 98% of the original black-tailed prairie dog population in the state has been lost and that only 300,000 prairie dogs remain. Surviving colonies are fragmented, and most cover <50 acres. Prairie dog habitat declined 61% from 1980 to 2000. At this rate of decline and habitat loss, prairie dog eradication could occur during the first half of the twenty-first century.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the black-tailed prairie dog as a species of least concern, and it does not appear on the federal or state lists of concerned species. The National Wildlife Federation recently petitioned the USFWS to list the species as threatened or endangered. The USFWS reviewed the status of the black-tailed prairie dog and announced its decision in February 2000 that, although the status of the species warranted listing as threatened, further action to place it on the list was precluded by actions to address higher-priority species. The black-tailed prairie dog was added to the list of candidates for threatened status, and its status is reviewed annually. Eight western states, including Texas, are working together on a conservation plan for the species.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu