PLAINS POCKET GOPHER

Geomys bursarius (Shaw 1800)

Order Rodentia : Family Geomyidae

DESCRIPTION. These are medium to small-sized, dark-brown gophers with large, fur-lined cheek pouches. The body is thickset and appears heaviest anteriorly, from which it gradually tapers to the tail, widening a little at the thighs. The eyes are tiny and bead-like, and the ears are very rudimentary, represented only by a thickened ridge of skin at the base. Long, curved claws are present on the front feet for digging; the claws on the hind feet are much smaller. Dental formula: I 1/1, C 0/0, Pm 1/1, M 3/3 × 2 = 20. The upper incisors have two grooves. Averages for external measurements: total length, 236 mm; tail, 65 mm; hind foot, 31 mm. Weight of males, 180–200 g; of females, 120–160 g.

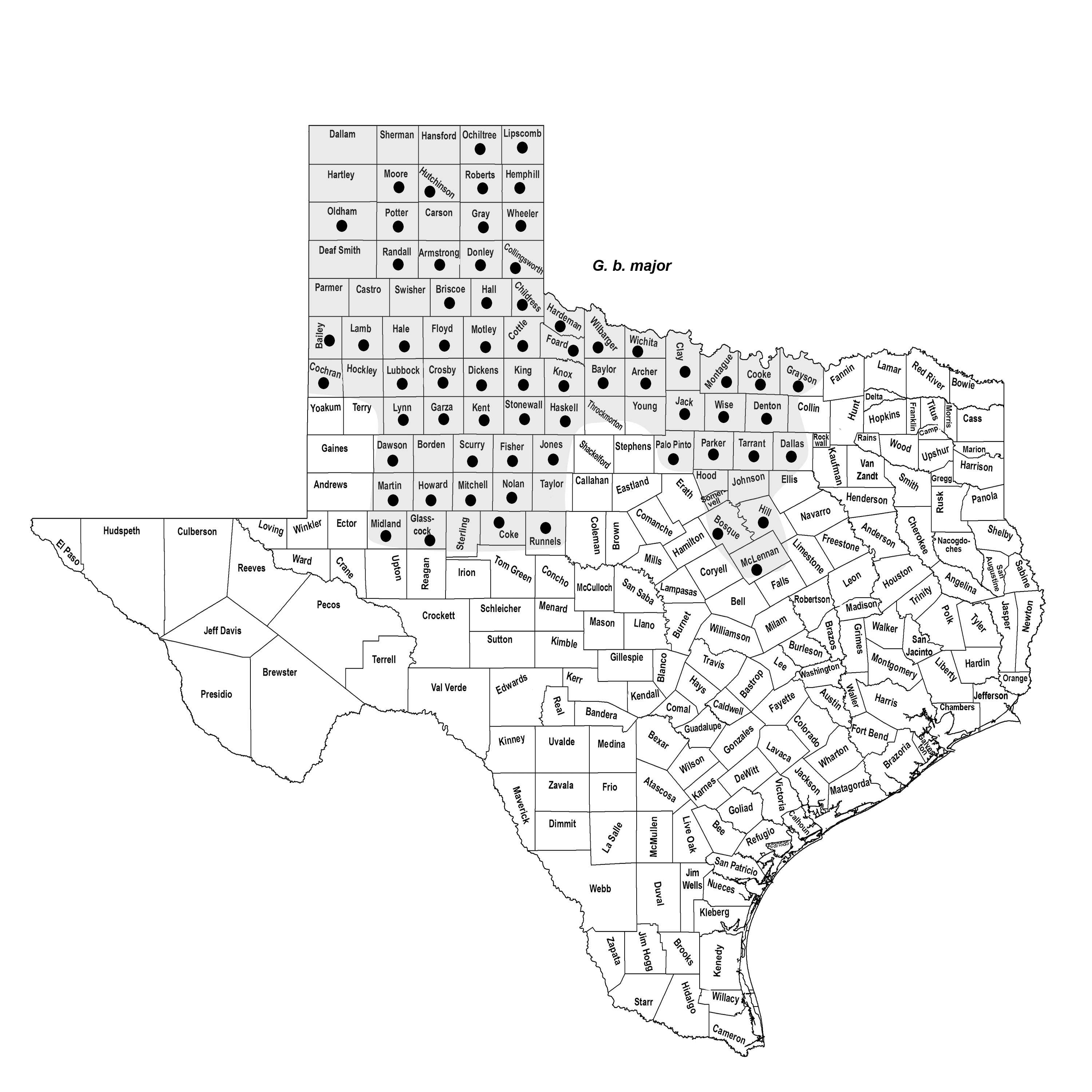

DISTRIBUTION. Northwestern and north-central Texas, south to Midland County in the west and to Grayson, Dallas, and McLennan counties in the east.

SUBSPECIES. Geomys b. major.

HABITS. This pocket gopher typically inhabits sandy soils where the topsoil is >10 cm. Clay and rocky soils are avoided. These gophers live most of their solitary lives in underground burrows, coming to the surface only to throw out earth removed in their tunneling efforts and occasionally to forage for some items of food. They seldom travel far overland although may do so when dispersing from the maternal territory. The average diameter of 40 burrows examined in Texas was nearly 6 cm; the average depth below the surface was 14 cm, with extremes of 10 cm and 67.5 cm. Much of their burrowing is done during foraging. The underground galleries attain labyrinthine proportions in many instances because the tunnels meander throughout a large feeding area. This is particularly noticeable under oak trees that have dropped a good crop of acorns. Burrows have been examined that extend >100 m (>328 ft.), excluding the numerous short side branches. Only one adult plains pocket gopher normally occupies a single burrow system.

The average mound constructed by these pocket gophers is about 30 × 45 cm, about 8 cm in height, and crescentic in outline. The opening through which the earth is pushed is usually plugged from underneath. The gopher digs with its front claws and protruding teeth, shoves the loose earth ahead of it with its chin and forefeet, and uses the hind feet for propulsion. Pocket gophers expend a substantial amount of energy burrowing, as is evidenced by the size of the huge winter mounds they make in poorly drained sites. One was 2 m long, 1.5 m wide, 60 cm high, and weighed an estimated 360 kg. The female that occupied this mound weighed 150 g. A typical winter mound contains numerous galleries, a nest chamber, a latrine, and food storage chambers.

These rodents feed on a variety of plant items, chiefly roots and stems of weeds and grasses. Most plant food is encountered and ingested while the gopher digs, but some grazing of food present along burrow walls probably also occurs. The fur-lined cheek pouches are used to carry food and nesting material but never dirt. Captive gophers have eaten white grubs, small grasshoppers, beetle pupae, and crickets; however, earthworms and raw beef were ignored.

Breeding begins in late January or early February and may continue through November. One litter a year, or two in quick succession, appears to be the norm. Litter size varies from one to six young. The young are nearly naked, blind, and helpless at birth. They remain with their mother until nearly full grown and then are evicted to lead an independent life.

As long as they remain in their burrows, pocket gophers are relatively safe from predators other than those that are specialized for digging, such as badgers and long-tailed weasels. When a pocket gopher leaves its burrow, however, it is highly vulnerable, and most predation losses probably occur on the surface. Known predators, other than those mentioned above, include coyotes, skunks, domestic cats, hawks, owls, and several kinds of snakes. As a result of the protection offered by the burrow, pocket gophers are long-lived relative to many other rodents, insectivores, and lagomorphs, living an average of 1–2 years in the wild.

In farming regions, these rodents can be destructive to crops and orchards. The amount of damage is closely associated with the number of animals. The average population density in eastern Texas is about 3.2 plains pocket gophers per hectare. The highest population density of record is 17.6 per hectare. These gophers can be controlled on small areas by trapping and on large ones by placing poisoned grain in their burrows.

POPULATION STATUS. Common. The plains pocket gopher is common in the north-central and western portions of the state.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the plains pocket gopher as a species of least concern, and it does not appear on the federal or state lists of concerned species. There do not appear to be any serious threats to its status.

REMARKS. Historically, G. bursarius has been considered one wide-ranging but morphologically variable species that was distributed over most of the Great Plains and south-central United States, including the Texas Panhandle and eastern Texas. However, recent studies by specialists trained in cytological and biochemical taxonomy have revealed that in actuality there are six species of pocket gophers ranging over these regions of Texas (designated G. bursarius, G. attwateri, G. breviceps, G. jugossicularis, G. knoxjonesi, and G. texensis). These are considered cryptic species, meaning that they cannot be differentiated on the basis of observed morphological characteristics although they are genetically distinct. Karyotypic, electrophoretic, and mitochondrial DNA data are required to confidently distinguish questionable specimens. With the elevation of G. b. jugossicularis to species status in 2008 by Hugh Genoways (University of Nebraska), RDB, and others, jugossicularis is treated under its own account.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu