COMMON MUSKRAT

Ondatra zibethicus (Linnaeus 1766)

Order Rodentia : Family Cricetidae

DESCRIPTION. A large, brownish, aquatic, scaly tailed rodent; feet and toes fringed with short, stiff hairs and toes of hind feet partly webbed; tail about as long as head and body, nearly naked, scaly, and compressed laterally; fur dense; eyes and ears small; upperparts brown to black, sides chestnut to hazel; underparts tawny brown, usually with a white area on chin. Dental formula: I 1/1, C 0/0, Pm 0/0, M 3/3 × 2 = 16. Averages for external measurements: total length, 516 mm; tail, 240 mm; hind foot, 74 mm. Weight of males, 923 g; of females, 839 g.

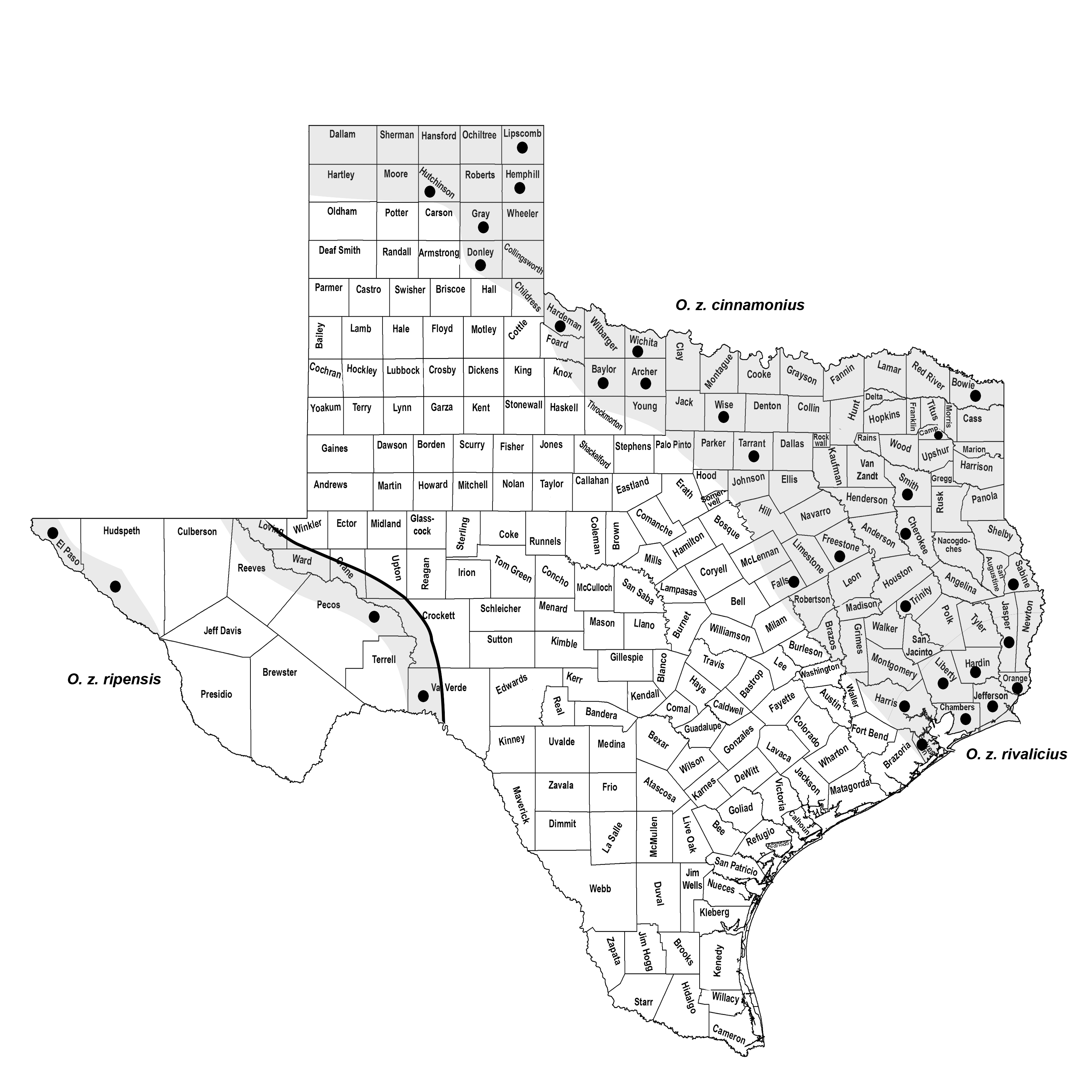

DISTRIBUTION. Occurs only in suitable aquatic habitats in northern, southeastern, and southwestern parts of the state.

SUBSPECIES. Ondatra z. cinnamominus in the north, O. z. ripensis along the Rio Grande and Pecos River in the Trans-Pecos region, and O. z. rivalicius on the Gulf Coastal Plain as far west as Brazoria County.

HABITS. Muskrats are principally marsh inhabitants; creeks, rivers, lakes, drainage ditches, and canals support small populations in places where requisite food and shelter are available. In the interior areas, shallow freshwater marshes with clumps of cattails interspersed among bulrushes, sedges, and other marsh vegetation support the heaviest populations; in coastal areas, the brackish marshes that support good stands of three-square grass (a sedge, Scirpus) are most attractive. Such marshes with a stabilized water depth of 15–60 cm seem to offer optimum living conditions.

In marshes, muskrats live in dome-shaped houses or lodges constructed of marsh vegetation. Access to the inner chamber usually is gained by means of two or more underwater openings, the plunge holes. Such houses are usually 60 cm or more in diameter at water level and project 50–60 cm above the water. They seem to be of two types: those used for feeding only, in which case the floor may be submerged in water, and those used for dens or resting places. Frequently, several animals (usually members of one family) occupy one lodge. Conspicuous travel ways radiate from the houses and lead to forage areas. In locations such as canals, creeks, and rivers, where house construction would be out of the question, the muskrats burrow into the banks and live belowground. Entrance to such burrows also is usually by means of underwater openings. Dens that have been excavated were about 10 cm in diameter and 2–3 m in length and usually terminated in an enlarged nest chamber.

The food of muskrats is varied, principally vegetation. Where available the tender basal parts of cattails and rushes are the main food source. In the brackish marshes of Texas and Louisiana, sedges are the primary food item. Normally, the animals have well-established feeding stations at the edges of travel lanes or in feeding lodges to which pieces of food are taken and consumed. The animals are active throughout the year and store no food for winter use. During winter, when nutritious food is scarce or made unavailable by freezing weather, the muskrats will eat almost anything, including parts of their lodges and nests, dead fish, frogs, wood, and so forth, or they may turn cannibalistic and prey on their own kind.

In southeastern Texas, the animals breed throughout the year. Breeding females produce two or more litters a year, ranging in size from 1 to 11 and averaging about 6. The gestation period is 22–30 days. At birth, the young are blind, almost naked, and helpless and weigh about 21 g. The pelage develops rapidly, and by the end of the first week the young are covered with a good coat of gray-brown fur. Their eyes are open in 14–16 days, at which time they can dive and swim with alacrity. When 4 weeks old they are generally weaned. Sexual maturity is reached in 10–12 months, at which time the muskrats have attained the size and characteristics of adults.

Muskrats are the victims of many predators. Hawks, large owls, raccoons, foxes, mink, water snakes, and large turtles are known to feed upon them.

The muskrat was, at one time, the most economically important furbearing mammal in eastern Texas, but this is no longer true.

POPULATION STATUS. Uncommon. In some regions of the state, common muskrats appear to have declined or even disappeared, whereas in other regions they have invaded and increased in abundance. Today, they are reasonably common along the upper Texas coast but are rare along the tributaries of the Canadian River in the Panhandle as well as from the springs and tributaries associated with the Pecos River and the Rio Grande.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the common muskrat as a species of least concern, and it does not appear on the federal or state lists of concerned species. The decline of permanent natural surface water, especially the drying up of freshwater springs as a result of irrigation, followed by the reduction of true marsh habitat, has caused their demise. The muskrat could be vulnerable to the rapid expansion and spread of the nutria (Myocastor coypus). This is a species that should be carefully monitored in the future.

Jon Falcone, a graduate student at Sul Ross State University, is investigating muskrats along the Pecos River drainage to determine if they represent a historic and isolated subspecies.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu