Presenting Conference Papers and Posters in the Humanities

Prepared by David Forrest

Teaching, Learning, and Professional Development Center

This paper is intended to describe the process of presenting research at conferences and provide useful advice for developing quality presentation materials. Although primarily directed at the new researcher, experienced scholars will also find some useful tips for improving their presentations. Be sure and check out the annotated list of online resources at the bottom of the page.

Introduction

Research conferences are the life-blood of academia. Scholars from around the country converge to exchange ideas, comment on each others' research, and find out what others in the field are studying. By participating in these conferences, students and professors can stake their research territory, network with others in similar subfields, and participate in the community of scholars. Two of the most popular methods of sharing research are paper presentations and poster presentations. Presenting papers and posters is an invaluable way to develop and prepare ideas for publication. The success of your conference participation depends on both the quality of your research and quality of your presentation. Many quality projects have suffered from poor presentation. The consequence of poor presentation is a lack of recognition and a lack of feedback from colleagues and experts in the field. Conversely, the better your presentation the more valuable feedback you will likely receive. Below are some suggestions and resources for preparing an effective presentation of your research.

Presenting Papers

Logistics

Conferences program committees will typically send out a call for proposals a few

months ahead of the conference. The call will request an abstract or proposal, typically

200-500 words in length. The committee will then select the best proposals and put

the program together. While individual conferences will vary, a typical paper session

allows presenters 15-25 minutes to lecture on their research project and then field

questions from the audience. Often, presenters will be grouped by paper topic into

a session. The session chair will introduce each presenter and facilitate audience

questions.

Talk to colleagues and mentors to find a conference that matches your interests. Also enlist their help when writing your proposal or abstract. For more advice on finding a conference and writing a solid abstract, see The Art of the Conference Paper.

Suggestions

A good practice for preparing for a presentation is to (1) write the research paper

(10-20 pages), then (2) translate the paper into speech-appropriate language. Writing

out the document insures that you completely explore the topic and have a well-constructed

argument. It also gives you practice preparing for publication; and sometimes a session

chair will want to read your paper ahead of the conference to prepare some questions

of his/her own. However, most research papers make poor speech scripts so it is important

to translate your paper into language that communicates well orally. Consider your

audience; reading an article silently is very different than listening to a presentation.

A reader can skip ahead or re-read a section of prose that was dense or unclear.

An oral presentation happens in real time. The same sentence might be clear for a

written document but difficult to follow when spoken aloud. Dense jargon, lengthy

quotations, and long, complicated sentences can lose your audience. In her article,

Conference Rules, Linda Kerber's “Rule No. 2” gives some very helpful advice on this translation process:

“Although a sentence linked by semicolons, or constructed with one or more dependent

clauses, may be perfectly clear on paper, it is very hard to understand when it floats

into the air. The listener cannot hang on to the subject until the object heaves into

view three clauses later.” Also see Presenting Conference Papers in the Humanities for more detailed tips on how to prepare the speech of your presentation.

To help communicate your lecture, consider using presentation software such as PowerPoint or Keynote. Before you decide to use technology of any kind, be sure and check with the conference organizers to know what technology will be available in your presentation room. For helpful tips on designing a quality slide show, as well as avoiding some technological pitfalls, see the TLTC's How can I use PowerPoint more effectively?

The best advice when preparing your presentation is to practice, practice, practice. Practice out loud, practice alone, for your friends, family, and colleagues, for anyone who will listen; and ask your practice audiences for feedback. Practicing will help insure that you stay within your time limits, are comfortable communicating orally, and that you are communicating clearly. In a well-designed presentation, even a novice in the discipline should be able to follow the gist of your argument. Ask a mentor or colleague to help you anticipate what questions people may ask about your paper. This will help you formulate some good responses and avoid getting stuck.

Finally, check with the societies and organizations within your discipline for field-specific advice. For example the American Historical Association features a very useful paper on their website that describes the experience from the point of view of historians.

Presenting Posters

Poster sessions are very common in STEM disciplines (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), and their popularity is growing in the Humanities. Poster sessions allow conferences to host a larger pool of researchers. This is especially valuable for young researchers because it provides more opportunities for students to present their work. Conference attendees also have the flexibility to browse the research that interests them most.

Logistics

In a typical poster session, posters are displayed in a large room and, at an assigned

time, presenters stand next to their posters to explain their project to passersby.

Conference attendees browse the posters to find topics of interest. It is up to the

presenter to communicate the project clearly and in a way that will elicit good feedback;

so prepare your comments ahead of time as well as some notes to refer to if you need

specific information. As with the paper presentation, ask a mentor or colleague to

help you anticipate what questions people may ask. It's best to engage people actively

as they approach your poster. Be friendly and open to criticism and remember, you

want people to comment – getting feedback on your ideas is one of the purposes of being

there. Be prepared with some paper for taking notes in case someone shares a useful

idea or resource.

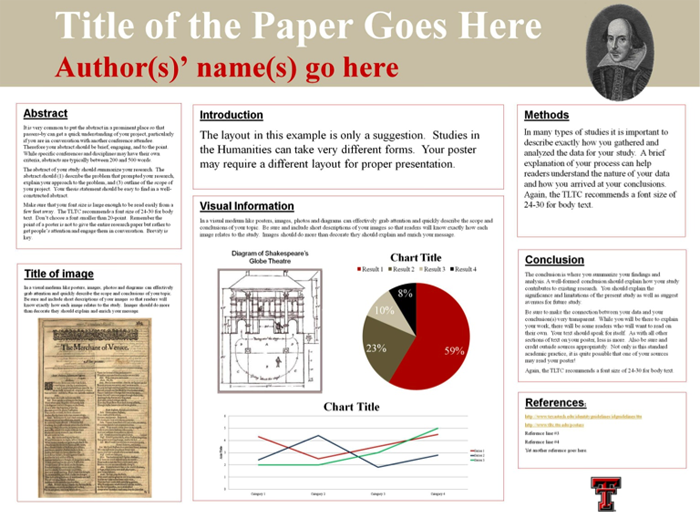

Poster Design

The poster should play a supporting role to your explanation of the project. At the

same time, it needs to be complete enough to allow people to learn about your project

if you are unavailable when they walk by. According to Elliott Moreton, a poster has three purposes: “To illustrate your explanation to the hearer when

you are there…to explain your work to the reader when you are not there…[and] to make people want to read your paper.” (p.1) Keep these purposes in

mind as you design your poster.

Just like with paper presentations, your written document will need some translation in order to make an effective poster. Inserting your 20-page written document into a poster-size sheet of paper will not communicate well. Posters are a form of visual communication so you should adjust your information delivery accordingly. Consider other forms of visual communication – billboards, print ads, television commercials. These examples use rich images and very little text. Charts, graphs, diagrams, photographs and other images can communicate your topic, data, and results more effectively than a large amount of text.

As Hess, Tosney and Liegel suggest, your poster should focus on one take-away point. There isn't room to include all of your findings and details, so don't try. Give your listener a clear presentation of your central idea. You will be there to expound on issues they find interesting or unclear. Have something physical to pass out – a handout or business card – with your email address or other contact information so that interested parties can contact you later.

Titling your poster

The title should be at the top of the poster and should be the largest text on the

poster (72-point or larger). A good title should clearly and concisely describe the

project. For example, here are two possible titles for an analysis of the music of

American composer, Aaron Copland.

Title Option 1:A Neo-Schenkerian Approach to Structural, Formal, and Prolongational Issues in Aaron Copland's Post-Tonal Juvenilia.

Title Option 2:How Tonal is Copland's Music?

Option 1 might be acceptable as an article title but would be ineffective as a poster title. It is too long and includes a weighty amount of jargon that doesn't communicate well to the passerby. The second option, set in large font at the top of a poster, will be more effective at getting people's attention and quickly communicating the aims of the research. Once a passerby shows interest, then you can expound on the central idea with more detail.

Click here to see a wide variety of actual posters courtesy of the Graduate School at the University of North Carolina.

Anatomy of a Research Poster

Check with the conference guidelines for specific expectations and limitations. The title and author(s) go at the top. Otherwise you have a great deal of freedom to choose what elements best represent your work as well as how to arrange them. In general, the body of most posters will have the following elements:

Abstract The abstract of your study should summarize your research. The abstract should (1) describe the problem that prompted your research, (2) explain your approach to the problem, and (3) outline of the scope of your project. Your thesis statement should be easy to find in a well-constructed abstract.

It is common to put the abstract in a prominent place (top center or top left, under the title and authors) so that passersby can get a quick understanding of your project, particularly if you are in conversation with another conference attendee when they arrive. Therefore your abstract should be brief, engaging, and to the point. While specific conferences and disciplines will have their own criteria, abstracts are typically between 200 and 500 words. Make sure that your font size is large enough to be read easily from a few feet away. The TLTC recommends a font size of 24-30-point for body text. Remember the point of a poster is not to give the entire research paper but rather to get people's attention and engage them in conversation. Brevity is key.

Conclusion The conclusion is where you summarize your findings and analysis. A well-formed conclusion

should explain how your study contributes to existing research. You should explain

the significance and limitations of the present study as well as suggest avenues for

future study.

Be sure to make the connection between your data and your conclusion(s) very transparent.

While you will be there to explain your work, there will be some readers who will

want to read on their own or while you are not around. Your text should speak for

itself. At the same time, as with all other sections of text on your poster, less

is more.

Visual data In a visual medium like posters, charts, photos, and diagrams can effectively grab attention and quickly describe the scope, data, and conclusions of your study. Be sure and include short descriptions of your images so that readers will know exactly how each image relates to the study. Images should do more than decorate the poster; they should explain and enrich your message.

References Be sure and credit outside sources appropriately. Not only is this standard academic practice, it is quite possible that one of your sources may be at the conference and read your poster!

Your contact information An email address at the bottom of your poster will allow people to send you comments and ideas even if you aren't there when they walk by.

Make sure every item on the poster relates directly to your one, central point – no distractions allowed. For specific advice including font choice and tips for interacting with PowerPoint see the TLTC Poster Printing Policies and Design Tips.

Conclusion

Be prepared to spend a good deal of time on the presentation aspect of your work. Careful preparation of your materials will dramatically improve how your work is received. For more advice, check out the online resources below. Good luck!

Texas Tech Resources

The Center for Undergraduate Research (CUR)

CUR assists with skills training and research funding and provides one-on-one mentoring

to undergraduate students in all phases of the research process.

How Can I Use PowerPoint More Effectively?

TLPDC white paper on designing a slide show to accompany a lecture or paper presentation.

Includes tips for avoiding technological disaster.

TLPDC Poster Design Tips

Includes specific advice including font choice and tips for interacting with PowerPoint.

Texas Tech PowerPoint Templates

Downloadable, free-use PowerPoint templates compliant with Texas Tech presentation

policies and preloaded with Texas Tech images including the official seal and “Double

T”.

- Works Cited and Other Online Resources

Angelini, A. 2010. The Art of the Conference Paper. Inside Higher Ed.

http://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2010/11/03/angelini, visited June 2011.

A graduate student reflects on lessons learned at a recent conference. Gives pragmatic,

bulleted advice for finding the right conference, writing a strong abstract, writing

the paper, and preparing and delivering the presentation.

- Claremont Graduate University Writing Center. 2011. Presenting Conference Papers in the Humanities.

http://www.cgu.edu/pages/864.asp, visited June 2011

Some helpful tips for translating your written paper into an oral presentation.

- Hess, G.R., K. Tosney, and L. Liegel. 2010. Creating Effective Poster Presentations.

http://www.ncsu.edu/project/posters, visited June 2011.

A comprehensive site that describes all aspects of poster design from developing your

idea, writing your abstract, and designing and presenting the poster. Includes a

discussion of software options and examples of good posters.

- Kerber, L.K. 2008. Conference Rules: Everything You Need to Know about Presenting a Scholarly Paper in Public. American Historical Association.

http://www.historians.org/perspectives/issues/2008/0805/0805pro1.cfm, visited June 2011.

Previously published in the Chronicle of Higher Education (March 21, 2008) and Perspectives on History (2008), this paper gives seven “rules” for using anxiety as an asset when presenting

scholarly work.

- Moreton, E. 2003. Posters. University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

http://www.unc.edu/~moreton/Materials/Posters.pdf, visited June 2011.

Good, concise advice on designing a poster and preparing for the day of presentation.

The section on poster construction is a little out of date (Moreton describes using

11”x17” sheets rather than designing with presentation software).

- Stanford University. Poster Design Guidelines and Resources for Undergraduate Research.http://www.stanford.edu/dept/undergrad/cgi-bin/drupal_ual/OO_research_opps_SURPSResources.html, visited June 2011.

Designed for Stanford's Symposium of Undergraduate Research and Public Service (SURPS), this site offers a range of advice on posters including Steps for Composing an Effective Poster and Tips for Posters in the Humanities.

- University of North Carolina Graduate School. Poster and Presentation Resources.

http://gradschool.unc.edu/student/postertips.html, visited June 2011.

An impressive metapage with links to advice on presenting, using PowerPoint with a paper presentation, poster design advice, poster design software, templates, and a nice selection of example posters. Links connect to a wide range of universities, corporations such as Microsoft,

and government sites.

Teaching, Learning, & Professional Development Center

-

Address

University Library Building, Room 136, Mail Stop 2044, Lubbock, TX 79409-2004 -

Phone

806.742.0133 -

Email

tlpdc@ttu.edu