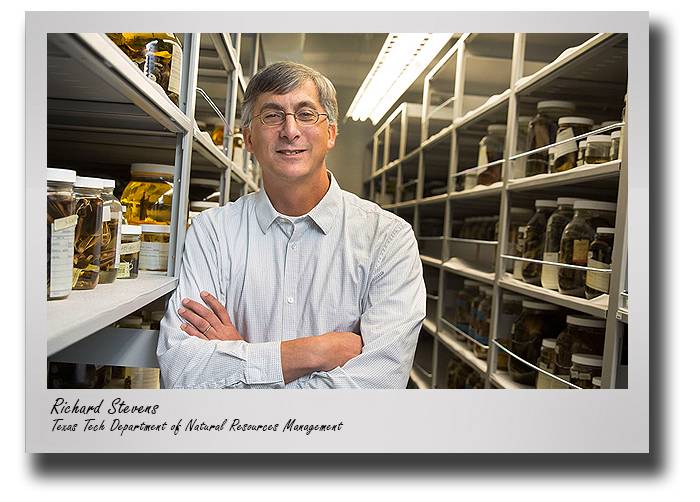

NRM’s Richard Stevens, TxDOT partnering to study Texas bat habitats

By: George Watson

Popular culture has long portrayed bats as menacing creatures to be feared for preying on innocent victims, turning them into vampires – or worse. In reality, bats play a vital role in the health of the ecosystem. Those that consume tons of insects on a yearly basis are crucial to the survival of local agriculture through elimination of these pests, protecting millions of dollars in crops every year.

Not all those bats live in caves. Many species occupy the culverts that run along

highways, including those in West Texas, as well as roosting on the underside of bridges.

Disturbing these habitats as little as possible is important to the bats' survival.

Not all those bats live in caves. Many species occupy the culverts that run along

highways, including those in West Texas, as well as roosting on the underside of bridges.

Disturbing these habitats as little as possible is important to the bats' survival.

The Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) has turned to Richard Stevens, an associate professor in Texas Tech's Department of Natural Resources Management to study how highway infrastructure positively influences bat distribution. TxDOT contracted with Stevens and his research team for almost $383,000 to study the multitude of bat species in the Trans-Pecos region of Texas, which has the state's greatest number of bat species, to determine why and how bats choose certain bridges and culverts as their roosting spots.

"TxDOT is interested in enhancing and creating habitats for wildlife," Stevens said. "TxDOT is interested in enhancing the economic impact bats have by consuming pests by providing them with roosts. If they provide them homes, especially in areas where they may not be currently living because of limited roost opportunities, then they can spread that economic impact into other areas of Texas or enhance that impact where the bats already occur."

Protecting Agriculture. Stevens said there are 33 different species of bats in Texas, most of which consume

a variety of insects, including moths, beetles, mosquitos, stinkbugs and termites.

These bats are capable of consuming as much as 85 percent of their body weight in

insects each night, and a roost of 150 bats is capable of consuming 1.3 million pests

per year, which could effectively disrupt the insects' population cycles.

Protecting Agriculture. Stevens said there are 33 different species of bats in Texas, most of which consume

a variety of insects, including moths, beetles, mosquitos, stinkbugs and termites.

These bats are capable of consuming as much as 85 percent of their body weight in

insects each night, and a roost of 150 bats is capable of consuming 1.3 million pests

per year, which could effectively disrupt the insects' population cycles.

Previous studies have shown a single Brazilian free-tailed bat, foraging in the Winter Garden region of South Texas, is able to consume 20 adult bollworms, a type of moth, in one night, and it is estimated that more than 100 million Brazilian free-tailed bats fly each night, roosting during the day in caves, culverts and highway bridges. Such a large population saves farmers from having to spend money on pesticides for their cotton crops, which results in an annual economic value to cotton of between $121,000-$1,725,000 for a crop valued at between $4.6 to $6.4 million annually for the region.

So it's easy to see how big the potential economic impact of bats can be for local agriculture. "There is a bit of a disconnect there: the things that do the most damage to crops are the larvae of the moths and beetles that feed off these plants," Stevens said. "Bats do not eat those, but bats eat the adults and particularly the females with all the eggs. By eating those females, they can prevent thousands to millions of eggs being deposited on a crop. That's a pretty big impact."

Protecting Bat Habitats. In order to ensure that bats continue to make that big of an impact – or potentially

bigger in the future – finding ways to properly maintain highway infrastructure while

enhancing bat roosting habitats is a focus for TxDOT.

Protecting Bat Habitats. In order to ensure that bats continue to make that big of an impact – or potentially

bigger in the future – finding ways to properly maintain highway infrastructure while

enhancing bat roosting habitats is a focus for TxDOT.

In order to develop the best practices that preserve bat habitats, Stevens and his team will spend the next three years examining bridges, culverts and other highway structures where bats may roost in the Trans-Pecos region to determine how and why bats choose certain structures and if they are part of small or larger colonies of bats.

"If you count all the bridges, probably 90 percent of all bridges in the Trans-Pecos region are in El Paso. So we are going to subsample only a small portion of El Paso," Stevens said. "It's outside of El Paso where we hope to systematically encounter every single culvert and bridge and determine if bats use them as roosts."

So it's easy to see how big the potential economic impact of bats can be for local agriculture. Stevens said culverts that cross divided highways usually range about 200-400 feet long and are about 5-10 feet underground. The thermal qualities of these culverts, he said, are believed to better simulate the thermal qualities of caves, which could be a factor in the bat's preference.

Bridges provide numerous nooks, crannies and expansion grooves that offer tight spaces for bats to roost in. Stevens also said a previous study by researchers at Boston University compared the development of Brazilian free-tailed pups raised in a cave to those raised under a bridge and found that the increased temperature of those bridges during the spring and summer resulted in pups that developed faster, weaned quicker, and had larger body sizes than those in a cave.

The low density of people in the Trans-Pecos region means that traffic over bridges is not as heavy as in other parts of the state, so bats are not as disturbed by noise. Thus researchers see heavier concentrations of bats in these bridges, another aspect Stevens and his fellow researchers will study.

Researchers will inspect bridges and culverts for bats, then count the number of bats per species they find. They will then take measurements of the bridge or culvert to determine size, the number of grooves or spaces where bats can roost and whether there are obstructions that prevent bats from roosting.

"What you have is a number of different bridge or culvert characteristics, and we want to understand whether bats are selecting certain things about the bridges or culverts," Stevens said. "But it could also be that the culvert or bridge characteristics are not important at all. It could be that habitat or landscape characteristics determine use by bats. So what we're doing, based on geographic information system (GIS) approaches, is characterizing the amount of different habitats that are associated with each culvert or bridge so we can disentangle the influence of bridge or culvert characteristics from characteristics of the landscape."

The field work, which began in early June, also includes monthly monitoring of a series of 20 bridges that have high concentrations of bats to characterize which seasons bats use them. Many bats in the Trans-Pecos migrate to Mexico in the winter, so Stevens is interested in how long bats use these structures, the period of time when they are not used and whether bats are using them at all.

While it is not a focus of this research project, Stevens and his fellow researchers will take advantage of their time in the field to mark, release and recapture a number of bats they encounter. Their hope is to determine which bats exhibit fidelity to one or a few structures, which are using a large number of structures and to better understand their behavior overall.

Between studying habitats or the ongoing epidemic of White-Nose Syndrome, which is lethal to many bats and has affected many in the eastern part of the U.S., the business of studying bats continues to grow. Texas Tech is one of the leaders in the field of bat biology with five researchers between the Department of Natural Resources Management and the Department of Biological Sciences.

"The study of bats is not exploding, but there is much more increased awareness of bats and much interest here at Texas Tech," Stevens said.

CONTACT: Richard Stevens, Associate Professor of Biodiversity and Conservation Biology, Department of Natural Resources Management, Texas Tech University at (806) 834-6843 or richard.stevens@ttu.edu

0803NM18

Davis College NewsCenter

-

Address

P.O. Box 42123, Lubbock, Texas 79409-2123, Dean's Office Location:Goddard Building, Room 108 -

Phone

(806)742-2808 -

Email

kris.allen@ttu.edu