CASNR's Joey Young uses Rawls Course to study water conservation treatments

By: George Watson

Over the course of the summer, thousands of feet will traipse across the greens at

the Rawls Golf Course north of the Texas Tech University campus. Those feet will drop

golf ball after golf ball in the 18 holes that make up one of the finest courses in

the country, both in design and appearance.

Over the course of the summer, thousands of feet will traipse across the greens at

the Rawls Golf Course north of the Texas Tech University campus. Those feet will drop

golf ball after golf ball in the 18 holes that make up one of the finest courses in

the country, both in design and appearance.

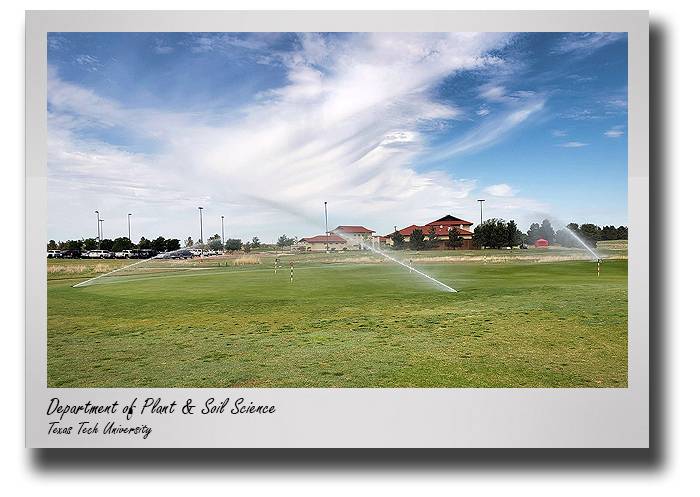

Management of the course takes tremendous amounts of work, energy and devotion from the dedicated individuals associated with the Rawls Course. They will employ every means at their disposal, from management practices to surface treatments and care, to make sure every golfer's experience is the best it can be. But little do those thousands of visitors know they also will be part of an experiment being conducted by Department of Plant and Soil Science assistant professor Joey Young.

Thanks to a grant from the Golf Course Superintendents Association, Young will use the Rawls Course practice putting green as part of an experiment hoping to better understand which turf treatments, also known as surfactants, best help golf course personnel maintain the grass when it comes to watering.

Young said the idea for the project came from Rawls Course superintendent Rodnie Bermea, who was curious to know more about how the different treatments used on putting

greens worked on the bent grass surfaces used at most golf courses in the northern

half of Texas.

Young said the idea for the project came from Rawls Course superintendent Rodnie Bermea, who was curious to know more about how the different treatments used on putting

greens worked on the bent grass surfaces used at most golf courses in the northern

half of Texas.

"They see research from all over the country and look at how the products are evaluated and how they perform in other places, but there's not a lot of direct data that they can take from our environment and our climate," Young said. "At that point, we saw there was an opportunity to write a proposal to the Golf Course Superintendents Association, so we decided to put something together and were able to get funding. There are four other state golf course superintendent associations providing funding, as well, to kind of double the amount of money we had to work with."

Over the course of the spring and summer, beginning just a few weeks ago, Young will treat different areas of the practice green at the Rawls Course with different surfactants to determine which ones help water penetrate the surface and which ones help the surface retain water.

Young also will measure artificially created ball marks that are created when shots land on the green to determine which surfactants allow for the quickest and most complete recovery from these putting green scars. The hope is to give golf course superintendents in the country, and maybe specifically, this area of the state, an idea of the best management practices in order to more easily maintain their courses while also reducing costs and the amount of water used.

"As an industry, there's a negative view in a lot of people's minds about golf courses using the quantity of water they do," Young said. "There was a study around 2013 or so that kind of talked about the water use compared to a survey in 2005. There had been a really marked reduction in water usage on golf courses for a number of different reasons. These surfactants are at the top of the list as to as to why the golf courses are able to maintain the same level of playing conditions and aesthetics with less water."

Surfactants, as used on golf courses or in other agrochemical means, are chemicals that help ground either retain water or help the water penetrate to the root system in order for the grass to grow. According to Young, most golf course putting greens are artificial-type systems with a sand-based root zone. This allows for the drainage of water more quickly and gives golf course superintendents the ability to manage nutrients and water that goes into the ground.

But because they are sand-based systems, there is a potential for the sand to become hydrophobic, where it repels water or there is a lack of attraction between molecules and the water. This makes it harder for the grass to grow. Surfactants are designed to alleviate some of the hydrophobicity that occurs.

Surfactants used for golf courses are marketed as either water-retaining products or water-penetrating products. Young said the surfactants being used in this study are used more strictly on golf courses but also can be used on high-end athletic fields, like some professional athletic or Division I collegiate fields, as well as households.

"I feel really confident that with the chemistries included in these products, there's definitely products that are marketed to homeowners that do, or at least claim to do, similar types of things," Young said. "So, there are comparable products, but the products we are using in this project are not really marketed to homeowners.

Through this study, Young is hoping to better determine which kinds of surfactants

work best on the creeping bent grass greens that dominate golf courses in this part

of the state. A combination of surfactants may provide the greatest benefit, but he

won't be spraying more than one treatment on any single square of the testing green.

Researchers will compare infiltration measurements of soil taken before the treatments

began in April and again at the end of the season, around October.

Through this study, Young is hoping to better determine which kinds of surfactants

work best on the creeping bent grass greens that dominate golf courses in this part

of the state. A combination of surfactants may provide the greatest benefit, but he

won't be spraying more than one treatment on any single square of the testing green.

Researchers will compare infiltration measurements of soil taken before the treatments

began in April and again at the end of the season, around October.

"If you've got a surfactant that's a retaining agent, you might see increased moisture content in the upper surface," Young said. "Whereas if it's a penetrant, we would expect to see a lack of water there, and that may or may not be good. It may end up being that the outcome is that you should balance retaining products and penetrant products so you can kind of get the best of both worlds. But we didn't want to mix them in this case, because it could have been difficult to distinguish benefits of individual products."

Perhaps the most entertaining part of this project involves the ball mark-measurement aspect, as it involves using a golf-ball launcher to pepper the putting green with balls to create consistent divots in the surface. Researchers then will use golf balls to measure the depth through image analysis. All ball marks will then be repaired and further image analysis will be used over the subsequent months to see which grass treated with a certain surfactant tends to repair itself.

From previous experience conducting similar research in a less arid region in Arkansas, Young saw that deeper ball marks recovered quicker than shallow ball marks. "That would be another thing that I think we'll be able to at least quantify the effects of ball marks with surfactants, and that's something I look forward to doing," Young said.

The whole goal of the project is to determine if the surfactants are as effective as they claim to be when marketed to golf course superintendents. Young projects that the products will live up to their billing after his research is finished.

"As we're measuring moisture in the very top inch and a half and up, the expectation is that the amount of water will go down with penetrants, but retainers should have more moisture," Young said. "Going beyond that to the laboratory setting, the marketing content is going to be accurate and correct, and their products that are designed to retain water will have more water and maybe slow infiltration a little bit because it's trying to hang on to the water and then the penetrants will increase infiltration rate."

As for the future, Young said the next step will be to conduct research that combines

treatments, i.e. spraying an area with one surfactant one month and coming back with

another surfactant the next month. The hope is to find the method that works best,

whether it is an actual combination of surfactants or using only one surfactant at

a time.

As for the future, Young said the next step will be to conduct research that combines

treatments, i.e. spraying an area with one surfactant one month and coming back with

another surfactant the next month. The hope is to find the method that works best,

whether it is an actual combination of surfactants or using only one surfactant at

a time.

"We know that most superintendents aren't just applying one thing. They're applying a lot of things," Young said. "So, from a real-world standpoint, to really know what the real benefits are, we probably need to have some of both, whether it's alternating applications between penetrants and retainers, or tank-mixing them all together and just spraying them out altogether. I think that from a moisture-management standpoint and a putting-green situation, this will be the next key question to answer."

Beyond that, Young said there also needs to be testing of treatments in different areas of the country, since not all golf courses are composed of the same soil, the same grass and other vegetation as on the South Plains.

"It may take even going south of Interstate-20, really and truthfully, to get to the Bermuda grass," Young said. "One of the benefits of doing research is that other people in other places see what you're doing and replicate what you're doing. So, there could be opportunities to collaborate with somebody who's in a location that has the opportunity to do half Bermuda grass and get a very good look at that without having to physically be there to make applications."

So if the practice green at the Rawls Course plays a little different this summer, you now know why.

CONTACT: Eric Hequet, Department Chair, Department of Plant and Soil Science, Texas Tech University at (806) 742-2838 or eric.hequet@ttu.edu

0522NM19

Davis College NewsCenter

-

Address

P.O. Box 42123, Lubbock, Texas 79409-2123, Dean's Office Location:Goddard Building, Room 108 -

Phone

(806)742-2808 -

Email

kris.allen@ttu.edu