PSS’s Young shows turfgrasses able to thrive under watering restrictions

By: George Watson

As the calendar turns to March and approaches April, and homeowners all across West

Texas begin to prepare their lawns for the upcoming warm weather, cities are also

dusting off their yearly watering restriction plans in order to conserve the state's

most precious natural resource.

As the calendar turns to March and approaches April, and homeowners all across West

Texas begin to prepare their lawns for the upcoming warm weather, cities are also

dusting off their yearly watering restriction plans in order to conserve the state's

most precious natural resource.

For years now, cities and towns all across the state have implemented restrictions on how much and what days homeowners and businesses can water their lawns if their water comes from a city-provided source. Those who irrigate their lawns using water from a well or some other source are not subject to those restrictions, though in some cities they are still encouraged to curtail their water usage.

Not only do these restrictions affect the water supply, but they also affect the health

and appearance of lawns. But to what extent hasn't been determined – until now.

Not only do these restrictions affect the water supply, but they also affect the health

and appearance of lawns. But to what extent hasn't been determined – until now.

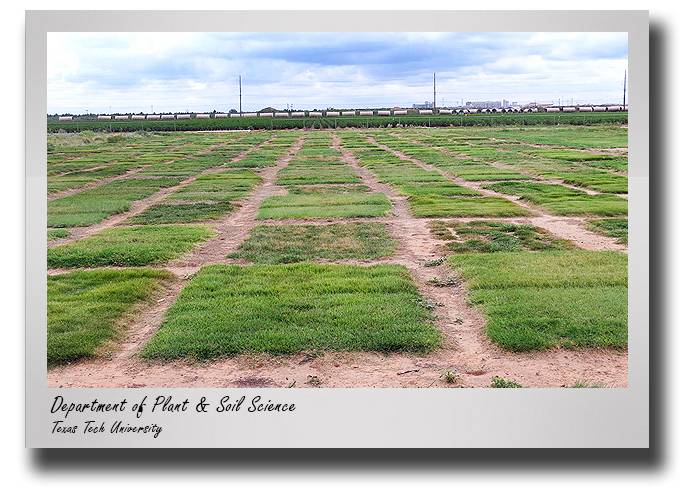

Joey Young, an assistant professor of turfgrass science in Texas Tech's Department of Plant and Soil Science, recently completed a study examining four different warm-season turfgrass species and their reaction to receiving both regular irrigation and only rain-fed irrigation.

"With our irrigation ordinance in town being that you can water two days per week, I was always a little concerned about telling people to not worry about not watering on your day," Young said. "You can water when your day comes back around. I felt confident that was probably the case. Now, I have more evidence-based information to say that we likely could go two weeks, in the middle of the summer, with really high temperatures and no rainfall, and the grass is going to continue to do perfectly fine."

Young's study showed that Bermudagrass, the most popular breed of turfgrass for landscapes in West Texas because of its ability to handle the harsh summer heat, is slower to go dormant under drought but also slower to wake up when water returns. In between it is very tolerant of heat and lack of rainfall. Native Buffalograss, which has high drought tolerance and low management needs, performed well under rain-fed only conditions, greening up more quickly than Bermudagrass after rainfall but also going dormant quicker as the soil dried.

The two other grasses – Jamur Japanese lawngrass and Zeon Manilagrass, both known as Zoysia grasses, have better cold tolerance than Bermudagrass but needed more water to remain green and thrive. They were also able to survive around two weeks without water and held their color well, but are slow to recover from dormancy.

"I think the more general take away that was important for me to see, and that I wanted to see, is that all of the grasses can easily survive a period of time without rainfall and without any irrigation," Young said. "Water is an important aspect of maintaining a turfgrass landscape, and depending on the use of that turfgrass landscape, water may be more imperative.

"But for the typical use of a residential landscape, and the aesthetics we should try to attain from that residential landscape, I think it's clear to see from work like this that, especially our warm season grasses have the capability of prolonged, healthy living with minimal irrigation or at least spacing it out more than what it may seem like you should or could do based on the city ordinance that is in place."

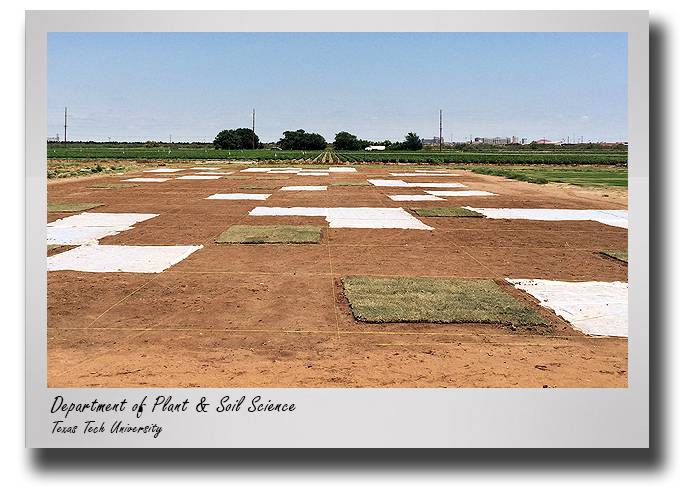

At the Quaker Avenue Research Farm just north of Fourth Street, 13 acres of land are dedicated to turfgrass research. This research area was fed by a subsurface drip irrigation system to study turfgrasses under different irrigation conditions that effectively and precisely deliver water in order to study turfgrass reaction.

Because Young's study needed to evaluate both how the grasses went dormant from summer drought and arose with rainfall under potentially extreme weather conditions, the study took years to develop and produce results, beginning with the sodding of the various turfgrasses in 2014. In all, this project was built on two years' worth of data, the bulk of the study occurring from July to early September each year when the grass was actively growing.

"Ultimately, we wanted to compare grasses in a semi-arid environment like Lubbock, where we get rainfall but then we get periods of time where there's limited to no rainfall for extended weeks," Young said. "How would turfgrass growth and color aesthetics compare when it's not irrigated compared to whenever we were applying irrigation through that subsurface drip system?"

Originally, Young hoped to evaluate the turfgrasses under four different irrigation

levels. But due to some problems with the irrigation system, the paper was boiled

down to turfgrass reaction under rain-fed conditions and irrigated treatment.

Originally, Young hoped to evaluate the turfgrasses under four different irrigation

levels. But due to some problems with the irrigation system, the paper was boiled

down to turfgrass reaction under rain-fed conditions and irrigated treatment.

Also, the plots of each turfgrass were divided by how closely they were mown at periodic times throughout the research – half the plot at 2 inches and the other half at 4 inches. Minimal fertilizer was applied in the late spring each year to kickstart grass growth.

The irrigation system was used very frequently during the time the grasses were active

– six days per week for 10 minutes per day. Irrigation also was used to promote growth

outside of the study's seasonal parameters.

The irrigation system was used very frequently during the time the grasses were active

– six days per week for 10 minutes per day. Irrigation also was used to promote growth

outside of the study's seasonal parameters.

"All of those grasses ultimately go dormant during the cool season of our typical year," Young said. "They're generally going to spend, even in a good year, probably about five or six months dormant, and they all look the same at that point, no matter what we're doing. So we really tried to focus irrigation around the summer months where we get the heat and we get a lot more water usage in our landscapes and the demand and usage goes way up."

Young said that, throughout the study, the key factor was they were always able to get that 3-4 week period where there was no rainfall, a crucial part of contrasting the effects of rain-fed irrigation and man-made irrigation. That is where Bermudagrass was able to separate itself from the other grasses with its ability to maintain its color longer. By comparison, Young said, Buffalograss quickly goes dormant without regular rainfall as part of its survival mechanism, and the Zoysia grasses could not keep up without supplemental irrigation.

Young hopes this evidence-based information will lead cities to implement watering restrictions based on scientific results, which will lead to more useful and efficient watering of landscapes.

"When you look at Lubbock, even in years where we get a lot of rainfall, the ordinance schedule has remained consistent," Young said. "So, come April 1, we're going to go into an ordinance that allows you to water two days per week. Then the-inch-and-a-half per week is kind of a total amount of water we can apply to our landscape based on the ordinance. That's going to end sometime in October with the thought, at that point, people are going to really kind of cut back on watering in general.

"But I think if you look across the country, especially as our urban areas continue to expand, in a lot of cases, which means more residential housing, which leads to more turfgrass within landscapes. The demand for the water outside continues to increase with population growth. That's why this kind of research is going to be important, to demonstrate and allow people to recognize that the grasses are capable of handling a little bit of stress and don't need to be babied all the time."

Of course, Young admits, this research applies mostly to the semi-arid areas around the country like Lubbock. In places like Dallas-Fort Worth, for example, the watering restrictions are different just because of the higher number of people that live there. They get more rainfall annually in those areas but have similar restrictions because of the higher demand.

Young also hopes those with wells, who are not subject to city water restrictions, recognize their grass can handle a certain period without water and will voluntarily cut back on their water usage, whether that's for residential lawns or commercial landscapes. He likens it to the request made of farmers to cut back on water because it all comes from the same pool.

These results also show the need to continue to develop turfgrasses that are more heat- and drought-tolerant with the persistence of climate change. Young said the warming of the climate won't really outpace the capability of these grasses to handle extreme heat for a certain amount of time, per se. But the more it is understood what grasses are capable of handling, water can be reallocated to use within the home and other, more crucial needs.

Young said grass breeders also are working on the problem by developing types of Bermudagrass, Kentucky Bluegrass, tall fescue, seashore paspalum and other types that are more tolerant to extreme conditions and other abiotic stresses, similar to what is happening with research into crops such as cotton, soybean, sorghum and others.

Young would like to continue this research in terms of evaluating different fertilization rates or fertilized vs. non-fertilized grasses and their reaction to drought tolerance.

"We continue to talk about it here from this perspective, but in the same way, farmers have better technology today than they had 10 or 15 years ago," Young said. "Turfgrass is moving in the exact same direction. The challenge is going to be that turfgrasses are more of a perennial crop that you're not just changing out all the time. So how do we change from what we have to this new, shinier, more stress-tolerant variety of landscape?"

CONTACT: Joey Young, Assistant Professor of Turfgrass Science, Department of Plant and Soil Science, Texas Tech University at (806) 834-8457 or joey.young@ttu.edu

0317NM20

Davis College NewsCenter

-

Address

P.O. Box 42123, Lubbock, Texas 79409-2123, Dean's Office Location:Goddard Building, Room 108 -

Phone

(806)742-2808 -

Email

kris.allen@ttu.edu