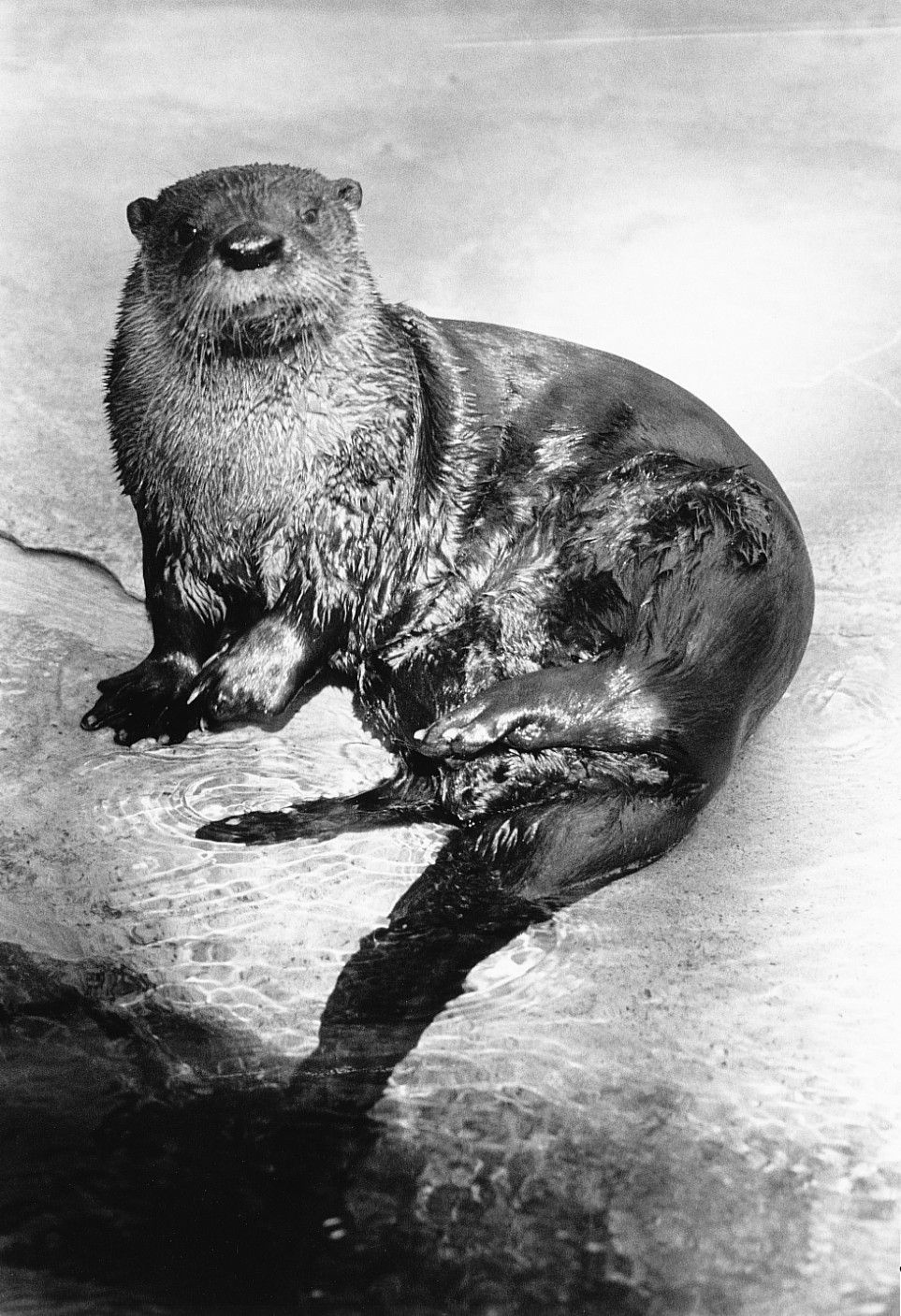

NORTHERN RIVER OTTER

Lontra canadensis (Schreber 1776)

Order Carnivora : Family Mustelidae

DESCRIPTION. Looks like a large, dark-brown weasel with long, slender body; long, thick, tapering tail; webbed feet; head broad and flat; neck very short; body streamlined; legs short, adapted for life in the water; five toes on each foot, soles more or less hairy; pelage short and dense; upperparts rich, glossy, dark brown, grayish on lips and cheeks; underparts paler, tinged with grayish. Dental formula: I 3/3, C 1/1, Pm 4/3, M 1/2 × 2 = 36. Averages for external measurements: total length, 1.2 m; tail, 457 mm; hind foot, 124 mm. Weight, 6–7 kg, occasionally as much as 10 kg.

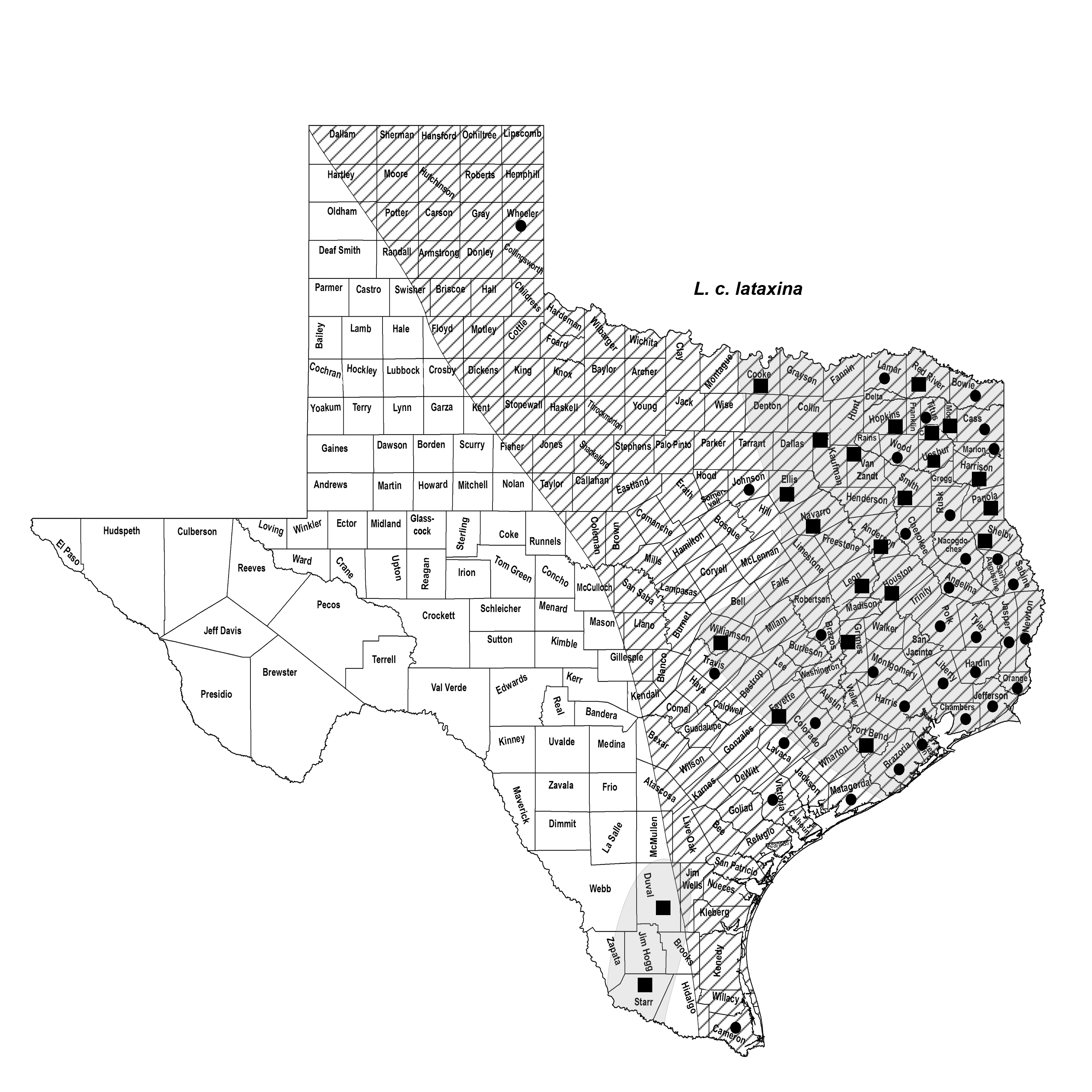

DISTRIBUTION. Historically, northern river otters ranged throughout eastern Texas and along the Red River drainage into the Panhandle as well as along the Brazos and Colorado rivers watersheds into central Texas. Today their range is limited to the eastern quarter of the state in the Pineywoods, Post Oak Savannah, and Gulf Prairies and Marshes ecological regions. Otters occupy a variety of aquatic ecosystems because they are very mobile and capable of long-distance dispersal. Ideal habitat is a deepwater swamp, which supplies both food and shelter, adjacent to a large, log-filled, fish-producing lake, which furnishes additional food and abundant water for swimming or play. Otters seemingly prefer clear rather than murky waters.

SUBSPECIES. Lontra c. lataxina.

HABITS. Most northern river otters locate their dens in excavations close to a water source. Dens may be located under tree roots, rock piles, logs, or thickets. The hollow bases of cypress trees and tupelo gums are especially popular. Occasionally, they will take over beaver lodges or muskrat dens for their own use after killing the occupants. A typical den consists of a hole leading into a bank, with the entrance below water level. Otters may occupy two dens, one as a temporary resting den and the other as a permanent nesting den.

Otters are sociable and playful mammals. Play is usually focused along water and seems to accompany many of the daily activities. They take particular delight in sliding down mud banks into the water.

Northern river otters have been studied in the coastal marshes of the J. D. Murphree Wildlife Management Area in Jefferson County. Eleven otters were captured in this area, and radio transmitters were surgically implanted so their movements could be monitored. Otter activity was greatest during the winter season and during the morning crepuscular period; it increased substantially with decreasing temperature. Male otters exhibited higher overall activity levels than did females. Otter home ranges averaged 337 ha, but activity centers averaged only 86 ha. These values are lower than those reported from other studies and probably reflect the plentiful and constant food supply in the coastal marsh. Otters did not make extensive long-distance movements away from the Murphree area. The average 24-hour movement was only 3.5 km (2 mi.), and the maximum movement recorded was 7.3 km (4.5 mi.). Otters did not show strong preference for individual habitat components within their home range. Barrow ditches and sloughs were most preferred, and bayous were least preferred. Most wetland habitat components were used in proportion to availability.

Otters are not specific in their food habits. Their main diet consists of fishes, crustaceans, mollusks, amphibians, reptiles, invertebrates, birds, and mammals. One of their preferred foods is crayfish, and where they are abundant, an otter will consume a tremendous number annually. The fish they eat are primarily rough fish. They also will eat aquatic plants such as pond weeds and roots. Otters typically search for food by swimming along the bottom, poking their nose and front paws into cracks beneath rocks, rooting around submerged logs, and digging in the mud.

Little is known about their reproduction in Texas. They probably breed in the fall, but males generally do not mate until they are 4 years of age, and females rarely breed before 2 years. Males typically engage in fierce combat during the mating season, and they are believed to be solitary except when accompanying estrous females. Estrous lasts 40–45 days, and the female is receptive to the male at about 6-day intervals. Mating usually occurs in the water. Delayed implantation results in the gestation period extending to as much as 270 days. Litter size varies from one to five, with two about average. Females may mate again as soon as 20 days following birth, which means that otters may remain continuously pregnant once they reach sexual maturity.

Newborns are about 275 mm in total length and weigh about 130 g. They are fully furred, but the eyes are closed and none of the teeth are erupted. Their eyes open at 22–35 days, and they are weaned at 18 weeks. The adult waterproof pelage appears after about 3 months.

Otters are long-lived animals capable of living 15–20 years in captivity. Other than humans, they have few natural predators. There are unverified reports of coyotes killing young otters and speculation that other carnivores and large birds of prey, as well as alligators, occasionally may kill them.

Even though their pelts command a high price, otters historically were not a major fur-bearing animal in Texas because so few pelts were harvested. Typically, otters are harvested in the Pineywoods, Coastal Prairies and Marshes, and Post Oak Savannah areas. Recent TPWD reports (2002–2013) indicate that the number of otters being harvested is on the increase; 3,797 otters were trapped and sold in Texas during this time period. These trapper reports indicate an increasing population and distributional range in Texas and that northern river otters may be making a comeback.

POPULATION STATUS. Uncommon. In the last few decades, concern was raised about the disappearance of northern river otters in many portions of their range as a result of habitat loss, heavy trapping pressure, and drowning in fish traps. In response to this concern, TPWD prepares reports on the status of the otter in Texas. These reports suggest that otters are increasing in abundance in much of their remaining suitable habitat. In fact, TPWD trapping reports (2002–2013) indicate that river otters have expanded their range into 20 additional counties in East Texas and now occur in 2 counties in the Rio Grande Valley. The highest density of inland otter was documented in the Sabine and Angelina–Neches River drainage of the Pineywoods region.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the northern river otter as a species of least concern, and it does not appear on the federal or state lists of concerned species. Apparently, the reestablishment and abundance of beaver and the improved habitat diversity and productivity associated with beaver activity have benefited the otter. Human-induced changes in habitat, such as impoundments, canals, and levees, are also providing improved conditions. It may be that this species no longer warrants monitoring.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu