Species account of the Eastern Spotted Skunk

EASTERN SPOTTED SKUNK

Spilogale putorius (Linnaeus 1758)

Order Carnivora : Family Mephitidae

DESCRIPTION. A small, relatively slender skunk (similar in appearance to S. gracilis) with small white spot on forehead and another in front of each ear, the latter often confluent with dorsolateral white stripe; six distinct white stripes on anterior part of body, the ventrolateral pair beginning on back of foreleg, the lateral pair at back of ears, the narrow dorsolateral pair on back of head; posterior part of body with two interrupted white bands; one white spot on each side of rump and two more at base of tail; tail black except for a small terminal tuft of white; rest of body black. Ears short and low on side of head; five toes on each foot, the front claws more than twice as long as hind claws, sharp and recurved. Dental formula: I 3/3, C 1/1, Pm 3/3, M 1/2 × 2 = 34. Averages for external measurements: of males, total length, 515 mm; tail, 210 mm; hind foot, 49 mm; of females, 473-170-43 mm. Weight of males, about 680 g; females, about 450 g.

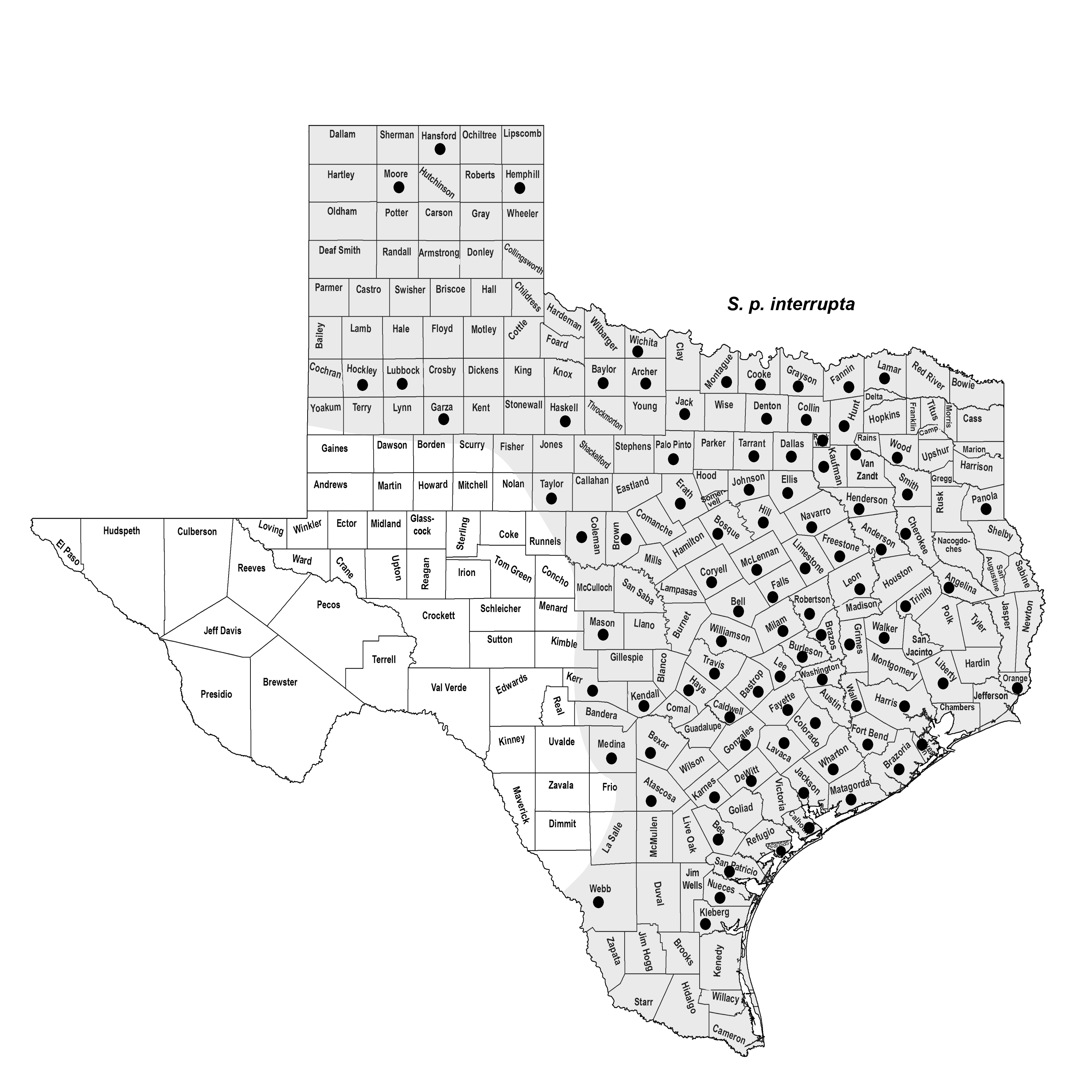

DISTRIBUTION. Occurs in eastern half of state, westward onto the eastern Edwards Plateau and through north-central Texas to the Panhandle as far south as Garza County.

SUBSPECIES. Spilogale p. interrupta.

HABITS. Spotted skunks occur largely in wooded areas and tall-grass prairies, preferring rocky canyons and outcrops when such sites are available. They are less common in the short-grass plains. In areas where common, they live around farmyards and often den under or in buildings.

Their den sites are varied. In rocky areas, they prefer cracks and crevices in the rocks or a burrow under a large rock. Given that they are expert climbers, they occasionally den in hollow trees or in the attics of buildings. In urban areas, they frequently live under buildings, in underground tile drains, and in underground burrows. They are almost entirely nocturnal and seldom are seen in the daytime.

Their food habits include small mammals, birds, insects, and fruits. Their seasonal natural foods consist of, in winter—cottontails and corn; in spring—native field mice and insects; in summer—predominantly insects, with smaller amounts of small mammals, fruits, birds, and birds' eggs; and in fall—predominantly insects, with small amounts of mice, fruits, and birds. Occasionally, spotted skunks kill poultry and may be considered a pest species.

Mating occurs in March and April. Some females possibly mate again in July and August and produce a second litter. The gestation period is estimated to be 50–65 days, with only a 2-week period of delayed implantation. The number of young in a litter may range from two to nine, but the usual litter consists of four or five young. At birth, the young are blind, helpless, and weigh about 9 g each; the body is covered with fine hair. The black and white markings are distinct. Their eyes open at the age of 30–32 days; they can walk and play when 36 days old, can emit musk when 46 days old, and are weaned when about 54 days old. When 3 months old they are almost as large as adults. Sexual maturity is reached at the age of 9–10 months in both sexes.

Predators of the eastern and western spotted skunks, other than humans, include dogs, coyotes, foxes, cats, bobcats, and owls. Their defensive behavior consists of a rapid series of handstands, which serve as a warning to aggressors. If approached too closely, they will assume a horseshoe-shaped stance, lift their tail, and direct their anus and head toward the potential aggressor. The foul-smelling musk can be accurately discharged for a distance of 4–5 m.

POPULATION STATUS. Rare. Once relatively common, this species is now rare in some areas, and its current status in the state is unknown.

CONSERVATION STATUS. The IUCN lists the eastern spotted skunk as a species of least concern, and it does not appear on the federal or state lists of concerned species. However, the subspecies, S. p. interrupta, was listed as Category 2 by the USFWS prior to 1996; now it is being considered for listing under the federal Endangered Species Act. Little is known about its status in Texas. Because these small skunks consume many insects, there is a concern that some of the population decline can be attributed to widespread use of chlorinated hydrocarbon insecticides, with the deadly effect passed (and concentrated) up the food chain. This is a species that requires careful monitoring in the future.

REMARKS. Robert Dowler of Angelo State University is beginning a research project that will include a review of the current and historical records of these skunks in the state, a habitat and fragmentation assessment to identify and quantify available habitat, field surveys to verify existing populations, and genetic analyses of populations across the range of the species.

From The Mammals of Texas, Seventh Edition by David J. Schmidly and Robert D. Bradley, copyright © 1994, 2004, 2016. Courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

Natural Science Research Laboratory

-

Address

Museum of Texas Tech University, 3301 4th street, Lubbock, TX 79409 -

Phone

806.742.2486 -

Email

nsrl.museum@ttu.edu