How one tragic event led to a half-century of life-saving research.

As part of Texas Tech University's centennial year, a lot of time has been spent looking back at the history of the university.

One of the focuses has been the history of research and how it has progressed over the past century, and that part of the story wouldn't be complete without talking about the 1970 Lubbock tornado.

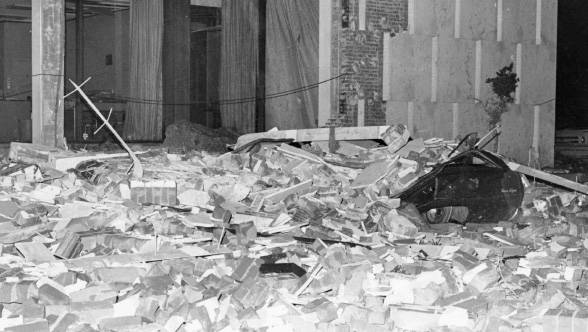

Photos by Lubbock Avalanche-Journal. Part of the 1970 Lubbock Tornado Photograph Collection, Southwest Collection/Special Collections Library, Texas Tech University.

On May 11, 1970, a powerful multi-vortex tornado brought devastation to Lubbock, claiming 26 lives. Though the events of that day were tragic, what arose from the carnage remains one of the most important areas of research at Texas Tech.

The research efforts in the days that followed led to improvements in building standards and assessing tornado damage. The efforts also laid the groundwork for Texas Tech to create the National Wind Institute (NWI), which is still among the most prominent and impactful research entities at the university.

Kishor Mehta, one of several young researchers from Texas Tech's Department of Civil Engineering to survey the destruction after the tornado hit Lubbock, made his way to Texas Technological College in 1964, when the university was only about 40 years old.

At the time, there was no structures laboratory, and he was allowed to have input into forming a facility where he could test structural components would look like.

“My (department) chairman had promised that when I came, we would establish a structural

engineering laboratory,” Mehta said. “The first couple of years, we just kind of conducted

a little bit of testing in the lab, as much as we could. It was a fun thing because

I was able to do what I wanted to do and design the lab the way we wanted it.”

The Lab of West Texas

The lab space, as it turned out, was less important than the location of Texas Tech.

Lubbock proved to be a natural laboratory for wind research.

Some of Mehta's earliest efforts were at Jones Stadium, where he and another professor, James McDonald, borrowed equipment from another department and placed sensors on the new stadium lights to test the impact of high winds on the flexible structure.

“That was our first attempt at what I would consider to be the real research. But we were not funded for it,” Mehta said.

Two years later, the tornado struck.

Mehta was at home that night grading final exams, but the morning following the tornado, he came to campus and heard about the extensive damage.

“The next morning when I came to the university, at that time, some information came out that it was a very severe tornado, and it had done a lot of damage to different types of buildings,” he said. “What triggered in my mind was that nature has done the testing for us. It is not a controlled testing like in the laboratory, but there is a lot of testing done, so there will be value in documenting that damage.”

A day after the tornadoes, Ted Fujita, a severe storms researcher and meteorologist from the University of Chicago, came to Lubbock to also assess the damage.

The data he gathered from Lubbock and other sites helped him to officially develop the Fujita Scale in 1971. That scale ranked the strength and power of tornadoes based on wind speed and the damage caused by wind.

‘Annoyingly Expert'

Ernst Kiesling was chairman of Texas Tech's civil engineering department in 1970. Kiesling died in 2021, but he spoke during the 50th anniversary of the Lubbock tornado about that time period and coming to Texas Tech to build a research program in civil engineering.

“We had a young faculty, including Mehta, McDonald, Joe Minor, and some other people who were looking for research areas, but we had very little going,” Kiesling said. “I viewed my appointment as chairman of civil engineering more or less as a mandate to develop a research program, because we had a graduate program in place, but no research to support it.

“The tornado provided a laboratory for us because there were lots of damaged buildings. We immediately went to work, and that was the start of the wind engineering program.”

Mehta worked with McDonald, Minor, Al Sanger, and Cliff Parish, as well as then-chairman Kiesling, to document and analyze the damage from the tornado. Ultimately, they spent a year investigating and writing a 400-page report on the tornado damage, which they later realized was one of the most detailed reports of its kind ever produced.

“That kind of got our name at the national level. We were doing some work that was good,” Mehta said.

This led to the professors going to the scene of other weather events and earning funding for research from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Mehta said Minor was from the Corpus Christi area, so he went back there to document damage from Hurricane Celia in August 1970, which led the professors to the realization that hurricane and tornado damage was very similar.

“Whenever there was a tornado in the surrounding area, we would go out and do the damage investigation,” Mehta said.

Their research area soon expanded to tornado damage in other states. A famous super tornado outbreak in 1974 saw Mehta go to Xenia, Ohio, while McDonald went to Paducah, Kentucky, and Minor went to Illinois.

The Ohio town hit by a tornado was much smaller than Lubbock but had a similar number of fatalities even though the population was lower.

“It was a very severe tornado,” Mehta said. “I did an investigation there looking at the schools.”

Mehta said the work led to the group becoming “annoyingly expert” at tornado damage investigation.

The researchers got funding from NSF, the Department of Civil Preparedness Agency, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which was interested in making sure a tornado would not take out a nuclear facility.

Mehta speaks frequently of Minor, McDonald and Kiesling, noting that they all worked together through what is now the NWI and helped each other find funding for their projects.

Lasting Impact

Mehta said they wanted to put Lubbock and Texas Tech on the map with their research. With the eventual creation of the NWI, and its work to understand wind, create wind-resistant building standards and harness the wind for energy, they succeeded.

“It definitely made an impact,” Mehta said of the group's research.

In 2009, faculty and students participated in Vortex2, the largest effort in history

to understand the origins and structure of tornadoes.

At one point, he went to Florida to investigate storm damage at a school where the

gymnasium collapsed. He said a teacher of young children moved her students into the

hallway during a tornado because of information the school was given from the National

Weather Service.

“I inspected that gymnasium. If she had not moved the children to the hallway, we would have received the fatalities of several young people,” he said. “What kills people is not the wind, but the building collapsing on them.”

Having better information based on investigations into previous storms may have saved those children's lives, Mehta said.

Schroeder said that sort of information was crucial, as was Kiesling's research into above-ground storm shelters. Schroeder calls Kiesling “the grandfather of above-ground storm shelters,” or reinforced interior rooms that can help people to shelter in place.

“I think about the legacy that he left: He saved lives,” Schroeder said of Kiesling's work.

Mehta and McDonald also picked up on the research done by Fujita in the 1970s. In 2006, improvements to the Fujita Scale were unveiled by the National Weather Service after being developed at Texas Tech.

People throughout the U.S. and Canada are familiar with news reports on storms using the Enhanced Fujita Scale, or EF-Scale, which rates storms on the severity of the damage they cause.

Continuing the Work

While many of the original members of the NWI team have moved on, research continues into wind that causes damage and wind that could power the world.

Over the years the NWI has helped lower the risks posed by tornados and helped engineer buildings that can better withstand the storms.

“Chances of surviving tornadoes are very high,” Mehta said, adding that in the future, things will be even safer because of ongoing research.

Damage still happens and lives are still lost but researchers at Texas Tech will continue to search for ways to mitigate disasters.

To Schroeder, more modeling capability is the future.

“We're starting to see a new era where it's not just about learning what didn't work. Now it's more about starting to turn the page,” Schroeder said, adding that science will lead to solutions and tornado-resistant construction.

Cooperation ultimately led to the scientists realizing in the 1990s that they could also be researching the positives of wind energy in addition to the negative hazards of wind.

“Things have just grown, and I think they've grown because if you look at the history, people were open to working together and we allowed things to evolve organically when it made sense to do so,” Schroeder said. “We were always very open-minded, and because of that, we've always evolved and grown.”