Deidre Popovich explains psychology behind seemingly irrational consumer choices.

If you have an account with any major retailer, you likely have dozens – if not hundreds – of items languishing in wish list purgatory, never to be purchased, their novelty already exhausted simply by virtue of your having previously considered them. Untouched and unopened, they somehow possess the quality of being used.

Deidre Popovich, an assistant professor of marketing at Texas Tech University's Jerry S. Rawls College of Business, examines this phenomenon in her extensive research on consumer decision-making.

After working for several years as a statistician, a marketing research manager and a strategy consultant for a large health care firm, Popovich enrolled in graduate school and pursued a career in academia.

“I was always doing research in the real world and, at some point, I decided I'd like to get a doctorate and conduct research in the academic world,” Popovich said. “The difference is that, in the academic world, you can study whatever you want, whatever is interesting to you. And I do find consumers to be very interesting, because we're all consumers.”

Popovich often finds inspiration for her research in the idiosyncratic purchasing behaviors she observes in strangers, her friends and herself.

“A lot of my research ideas actually come from things I've noticed myself doing, or my friends doing, or people around me doing,” Popovich said. “And then I think, ‘Hmm, I wonder why I did that. That doesn't seem very rational from a purely economic standpoint.'

“In the world of economics, we're supposed to be rational actors who act in our own best interest all the time. From a consumer psychology perspective, which is what I do, we realize that often isn't true in practice.”

Wish lists as impulse control

Popovich's research demonstrates that wish lists decrease the likelihood of eventual purchase by prolonging the decision-making process, extending what would otherwise be a one-stage decision into a two-stage decision and necessitating the reevaluation of items whose appeal may have waned in the interim.

“I got the idea for this research project because I have all these books on my Amazon wish list,” Popovich explained. “I thought, ‘I'm never going to be able to read all the books on this list, so why do I keep putting stuff on here? And why is it that once I put something on there, I don't buy it?'”

Consumers tend to take a maximalist approach during the first round of decision-making, liberally selecting wish list items according to their attractiveness and prioritizing form over function. However, consumers are much more discerning in the second round of decision-making, placing less weight on the more superficial, cosmetic features that might've drawn them to an item in the first place, and focusing instead on the item's practical, utilitarian elements.

According to “Intermediate Choice Lists: How Product Attributes Influence Purchase Likelihood in a Self-Imposed Delay,” an article co-authored by Popovich and Ryan Hamilton, “The attributes that are weighted more heavily in the decision to place an item on an intermediate choice list are then weighted less heavily in the decision to purchase an item from that list. ... This process tends to diminish the importance of the attractive attributes that encouraged consumers to put these items on lists in the first place.”

This protracted decision-making process seems to be universally beneficial to the consumer, promoting more conscious consumption by embedding impulse control into the shopping experience, and saving consumers money by decreasing frivolous purchases. Furthermore, while wish lists lead to fewer purchases overall, they facilitate higher purchase satisfaction in the long term.

“Because people are forced to think about a purchase at two different points in time – when they click the wish list button and when they click the buy button – they enjoy their purchases more. They've put more thought into their purchase decision,” Popovich said.

“If you put something on your list and eventually buy it at a later date, you'll probably be more satisfied with your purchase than somebody who just clicked the impulse buy button in the middle of the night.”

Implications for retailers

While purchase-delay devices seemingly pose no drawbacks to consumers, retailers must balance the advantages of wish lists with the potential of losing revenue in the form of unrealized purchases.

In their article, “Do Wish Lists Work?,” published in Rutgers Business Review, Popovich and Hamilton enumerate the ways in which wish lists benefit retailers, including providing consumer preference data and facilitating targeted advertising and promotions; enabling shoppers unable to make an immediate purchase to return at a later date; and creating brand loyalty through increased purchase satisfaction.

However, do these advantages outweigh the monetary cost of the purchases that never came to fruition? How valuable are those unread books in wish list purgatory, after all?

“Shopping cart abandonment is a pervasive challenge for retailers,” Popovich and Hamilton write. They advise retailers to draw consumers' attention back to the initial reasons they found a product appealing through persuasive advertising and email re-targeting.

“If retailers can encourage consumers to re-focus on initially important attributes, that might reverse the decline in purchase likelihood,” the article continues. “Persuasive advertising or email re-targeting of customers who have left something on a wish list or in a shopping cart might work. Anything a retailer can do to encourage customers to re-capture their initial attribute preferences may eliminate the reduction in purchase likelihood that comes from wish list use.”

Alternatively, retailers may choose to capitalize on consumers' two-stage decision-making process by emphasizing the more practical aspects of an item – the feasibility attributes that consumers are more likely to prioritize during their final round of decision-making.

Eat this, not that

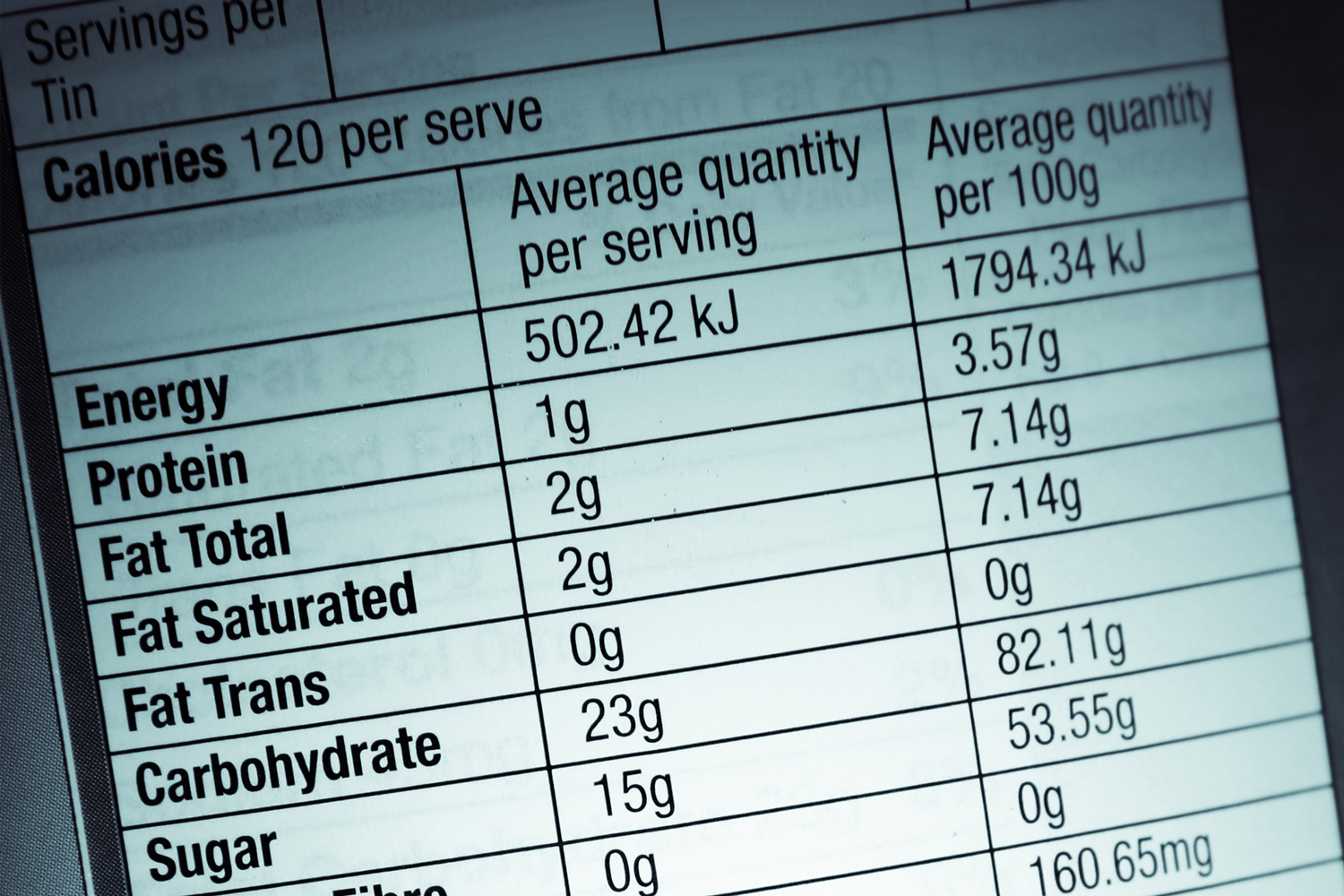

In 2008, New York City began requiring restaurant chains to post calorie information alongside menu items in the hopes that diners, armed with more nutritional information, would make healthier food choices. The results were underwhelming.

“Some economists did a study showing that after calories were added to the menus at Starbucks, for example, sales of unhealthy drinks increased,” Popovich said. “They've looked at the data in a lot of these studies, and sales of unhealthy items either stay the same or tend to go up.”

In 2016, the rest of the country followed suit and the Affordable Care Act mandated nationwide calorie labeling for restaurant chains with more than 20 establishments.

“We're inundated with this calorie information which makes us feel this false sense of familiarity, this false sense of understanding what that is,” Popovich said. “But when I ask people to think more deeply about what calories mean in the context of healthiness, it turns out they have no idea; it actually ends up backfiring in the sense that when I ask you to think about calories, you're going to rate fast food items as healthier than if I didn't ask you to first think about calories.

“I think to fully understand human behavior, we have to look at it through the lens of psychology. We can't just assume that people are human computers and are going to make the most optimal, rational decision all the time.”

Shopping for health care

Popovich and her colleagues recently were awarded a $1.2 million grant from BlueCross BlueShield of Texas to study consumer health care decisions and how those decisions are influenced by consumers' perceptions of the value and affordability of medical procedures.

“Interestingly, we find that people think all health care is similarly expensive, and most people have no idea what a procedure should cost,” Popovich said. “Obviously, in the U.S., most consumers think health care is incredibly expensive, whether we're talking about a minor procedure or a major surgery.”

This perception is hardly unfounded, as the U.S. spends more per person on health care than any other country, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. However, patients may be able to lower their medical expenses by shopping around for procedures from different providers, whose prices can vary significantly.

The backbone of the hospital billing department, and the source of this seemingly arbitrary pricing, is the chargemaster – a comprehensive list of medical services and their rates, which far exceed the actual cost of the procedures, supplies and medications.

The chargemaster originated in the mid-20th century as a negotiation tool between hospitals and health insurance providers. By artificially inflating the baseline prices of their services, hospitals were able to satisfy insurance companies' demands for steep discounts without actually sacrificing revenue, and insurance companies were able to reimburse hospitals for only a fraction of a patient's billed expenses.

Insured patients are somewhat insulated from chargemaster prices, rarely seeing the original billing amount of a service, but they experience the domino effect through mounting insurance premiums, co-pays and deductibles. Uninsured and out-of-network patients, on the other hand, are billed the original chargemaster amount.

While it's difficult to perform a cost-benefit analysis of lifesaving services during a medical emergency, patients with a little more time on their hands can utilize the internet to compare hospital prices before selecting a provider.

“Websites are popping up in the health care space to try to help consumers make more affordable decisions,” Popovich said. “If you need an MRI, there are websites with lists of providers and how much it costs. Increasingly, that information is being made available to consumers. But of course, when I talk about my work in this area, most people say, ‘Oh, I didn't even know I could go online and shop for these things – I had no idea health care was shoppable.'”

The Hospital Price Transparency Final Rule, which went into effect on January 1, mandates that U.S. hospitals provide pricing information on their websites so consumers can make more informed, proactive decisions about their health care. However, the way the hospitals choose to display this information can shift patients' perceptions of how affordable procedures are.

“There are lots of different ways you can portray costs to people,” Popovich said. “By changing something very simple about how information is presented – whether you're giving patients an average price, comparing the local average to the state average or just giving them a range of prices and saying, ‘the cost will be between these amounts' – you can drastically alter someone's interpretation and influence how they might behave in a certain context. These very simple shifts in how information is portrayed can have a big impact on consumer behavior.

“It's not enough just to throw information at people if they can't disentangle what it means. How can we make them more aware and make the information easier to interpret? That's what we're interested in studying moving forward.”