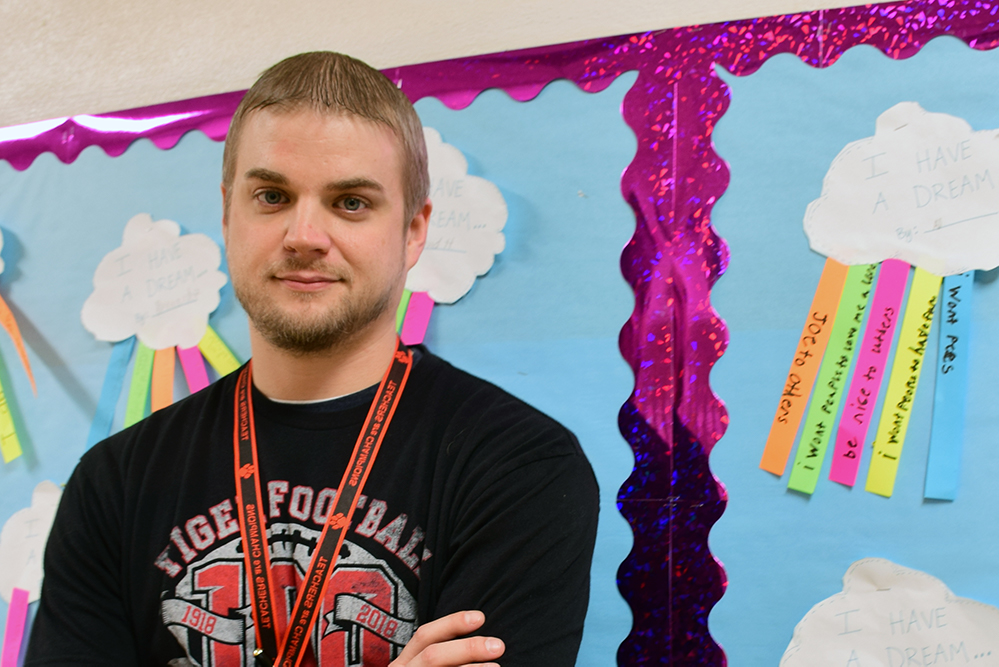

Rejecting school suspensions as the best answer to student behavior issues, Texas Tech University graduate Sam Thompson is rethinking the way discipline is doled out at Slaton ISD.

For many students, school suspensions can be a life-altering experience that sets them on a pipeline to prison.

Sam Thompson was one of the lucky ones. He spent a lot of time suspended or in alternative education programs while growing up in San Angelo, but he avoided slipping down that path.

Now, the recent graduate of Texas Tech University's educational psychology program is leading a large-scale initiative at Slaton Independent School District to rethink the way it addresses social and behavior problems. The goal, Thompson said, is to give more students at the small, rural district a chance to thrive.

"When a kid messes up, we want to give them the idea that it's an opportunity to learn, not an opportunity to be punished," Thompson said.

He was first introduced to Slaton ISD while doing a practicum as a master's student at Texas Tech. After completing his educational psychology degree in 2013, Thompson joined the district as a school psychologist and worked there while completing a doctorate in the same field.

With school shootings making the news about the time of his arrival at Slaton ISD, district administrators decided to see what could be done to address behavior problems before things turned violent.

The district, with Thompson's urging, decided to implement Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS), and it named Thompson head of the initiative in July.

The system is a rarity in rural, West Texas schools. Traditionally, a school psychologist will screen individual students to see if they should be placed in special education classes. In MTSS, school psychologists oversee a broader, districtwide effort to continually screen all students and provide intervention, which can be intensified depending on how much a student is struggling.

"Instead of using me as a firefighter, why not use me as a contractor to build a house that won't catch on fire?" Thompson said.

"That's kind of a different use of the school psychologist. We're very good at dealing with behavior that's way off the rails. We're also good at keeping behavior from going off the rails, but we're typically not used for that."

Early prevention

The changes at Slaton ISD, a 1,300-student district about 20 miles southeast of Lubbock, have resulted in a steep decrease in punitive discipline practices like suspensions and office referrals.

The district has stopped sending students to disciplinary alternative education programs (DAEPs) for all but the offenses that the State of Texas deems a mandatory offense, such as assault or selling drugs on campus.

If a child trips another student and breaks their nose, for example, instead of assigning blame and excluding the offender from class, specialists focus on repairing the relationship between the two students. This approach leads to emotional and social learning and helps create a supportive school environment, Thompson said.

"We can punish the bully, but it doesn't make the other student's nose feel better and it doesn't take away the embarrassment he had whenever he fell," he said. "That shame can last forever, literally forever. And we see instances of shooters who harbor those feelings and take them back to their old schools."

Interventions under MTSS take a holistic approach. Instead of handing out a punishment when a student has been racking up tardies or absences because a family member is sick and unable to care for them, an MTSS specialist might go to their house and provide eight weeks of food, a slow cooker and lessons on meal preparation.

MTSS focuses on early prevention, which is especially beneficial for schools like Slaton ISD that have large populations of minority and economically disadvantaged students since those students tend to be suspended at disproportionate rates. While removing misbehaving students from school is often seen as a quick fix for educators, research shows the punishments can hurt student achievement and place youngsters on a path to incarceration.

"Coordinating services and resources through the lens of early intervention and prevention is proving to be very successful with our at-risk population," Slaton ISD Superintendent Julee Becker said. "The work of coaching students on appropriate reactions to the rhythm of life is actually changing lives."

To implement MTSS, Thompson coordinates a group of eight professionals, including two licensed professional counselors, a certified school counselor, three school resource officers and the district's superintendent and assistant superintendent. A district parent also works with the group as a community liaison.

Thompson even works with general educators and staff to give them the skills to evaluate students and provide appropriate interventions.

"A teacher has more power than they think they might, and them sending a kid out of class is not necessary going to fix the problem," Thompson said. "We want to give teachers the skills to go after the function, the why, behind the behavior."

An 'incredible need'

People who work as school psychologists frequently report that it is a rewarding job.

U.S. News and World Report recently ranked school psychologist as the No. 2 profession in the nation in the category of social service jobs. Among all jobs nationwide, school psychologist placed No. 45.

Still, there is a great demand for school psychologists, particularly in rural parts of Texas. The recommended ratio of students to psychologists for a school district is between 500-to-1 and 700-to-1.

In Texas, there is just one psychologist for every 4,000 students, said Brook Roberts, director of clinical training and field education in Texas Tech's educational psychology program.

"To me, that shows the incredible need we have to train more school psychologists in the field to address a number of rising problems," Roberts said.

"Schools all over Texas – large and small, rural or urban – need innovators to push the practice of school psychology forward and ensure that all children have an opportunity to succeed. We at Texas Tech are proud to be training the next generation of leaders in school psychology. Our impact can clearly be seen in graduates like Sam."

Texas Tech recently formalized a new school psychology track for its educational psychology master's degree program that is ideal for professionals such as special education teachers, educational diagnosticians or school counselors seeking to advance their careers.

The 60-hour program combines face-to-face classes with the flexibility of some coursework offered online, on weekends and in intensive, one-week summer sessions.

The program also features carefully mentored community and school-based experiences that accompany coursework during each year of study. In Thompson's case, his experience doing a practicum at Slaton ISD led to a job.

Repaying the faith

The work of psychologist Ivan Pavlov interested Thompson during his undergraduate classes – bells, meat powder and conditioning. Thompson wanted to know why people acted the way they did.

Pair that with a desire to work with children, and the school psychologist route made perfect sense.

The whole endeavor is ultimately about providing opportunities for young people who might be struggling, Thompson said, recalling his early behavior issues in school and later difficulties while earning his degrees.

"I'm a firm believer that chances should abound for people, and Texas Tech is a university that agrees with that too," he said. "I was on academic probation at Texas Tech, and I left with Ph.D. in good standing.

"My choices at the time had the power to sink my future, but I was attending a university that saw things differently. They gave me another chance and I've been happy to repay that faith."