Texas Tech assistant professor Daniel Kelly received an honor and a $587,700 career grant for his outreach to at-risk youth who face issues like he once did.

Daniel Kelly could not care less about academics at 15 years old.

By the time he was a sophomore in high school, he had already attended about 10 different schools and decided to drop out.

“It was a rough couple of years,” Kelly recalled.

He was in foster care and had been removed from his home into a group home. And while he was not enrolled in school, he was still learning lessons – the hard way.

“Having an education is very powerful,” Kelly said. “I learned really quickly when I wasn't in school not just the value of school, but what it costs if you don't have it.”

Kelly may have given up on high school, but his supporters at his group home and beyond did not give up on him. They convinced him to enroll in a vocational electrical trades program that sparked his interest in learning.

“It was the first time I was very successful academically,” Kelly said. “It allowed me to then transfer that success to my high school.”

It may seem ironic that 25 years later, Kelly has dedicated his life to the field of education as an assistant professor of STEM Education in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction in Texas Tech University's College of Education.

But for Kelly, it is less a job and more a personal mission.

“I really wanted to hopefully get in the path of kids like me and redirect them to positive outcomes,” Kelly said.

And according to the International Technology and Engineering Educations Association (ITEEA)'s Distinguished Technology and Engineering Professional Board, Kelly does this effectively. The board honored him April 15 with the Distinguished Technology and Engineering Professional (DTE) designation.

The DTE honor, bestowed by a committee of expert peer reviewers, is one of the highest levels of achievement granted by ITEEA. It is earned based upon documented evidence of a high level of competence, continued participation in professional development programs, and demonstrated leadership in association, community and personal activities.

There are several ways Kelly meets those requirements, as he discovered while going through his curriculum vitae (CV): a detailed document highlighting his professional and academic history.

“Everything you do, it takes up two to three lines on the CV,” he said. “It never feels like you're doing enough and when you finally go through it, you go, ‘It's only been five years and look at what I've accomplished.' It really changes your perspective.”

The same week as his DTE designation, Kelly happened to add another significant line to his CV when he received a five-year $587,700 career grant from the National Science Foundation to bring robotics, programming and social-emotional learning to students who are either incarcerated, in a juvenile justice alternative education program or a high-needs economically segregated school.

“This funding is kind of an investment in the future of an individual's career,” Kelly said. “It's the first time I've been able to secure significant funding to continue my work here with a population that a lot of people don't pay attention to.”

Kelly never would have dreamed his disinterest in school would turn into him encouraging other at-risk students not to give up on education.

“I've had to fight for this program within the systems I work in, and this grant validates that all of that effort was worth it,” he said. “Now I finally have something I can point to and say, ‘This is why you need to pay attention.'”

Outreach Through STEM

Prior to his work at Texas Tech, Kelly was an assistant professor of technology, engineering and design education at North Carolina State. He also has served as a middle and high school science, technology and engineering teacher.

It was during that role at a middle school 10 years ago when Kelly's perspective on his past changed forever.

“I had a kid who was in foster care and he was really open about what he had gone through,” Kelly said. “He inspired me because I was like, ‘If he can do it, I can share my story.'”

Instead of keeping his troublesome upbringing a secret due to embarrassment, Kelly said he began to wear it as a “badge of honor.”

He even published a book titled “Falling Down: A Teenager's True Story of Redemption” to highlight his struggles and give perspective to families facing similar issues. He donated proceeds from the book to organizations that help at-risk youth.

But he wanted to do more. By the time Kelly applied to work at Texas Tech in 2017, he had a specific request during his interview that was outside his potential job description.

“I started an informal learning program that year called the STEM Explorers to provide STEM educational activities for children in foster care,” he said. “I remember in my interview I said, ‘I want to bring this program here, and if you're not interested, then I'm not either.' I still can't believe I said that.”

To Kelly's surprise, he was not only given the green light, but encouraged to continue what he calls his “labor of love” on the Texas Tech campus once he was hired as faculty in 2018.

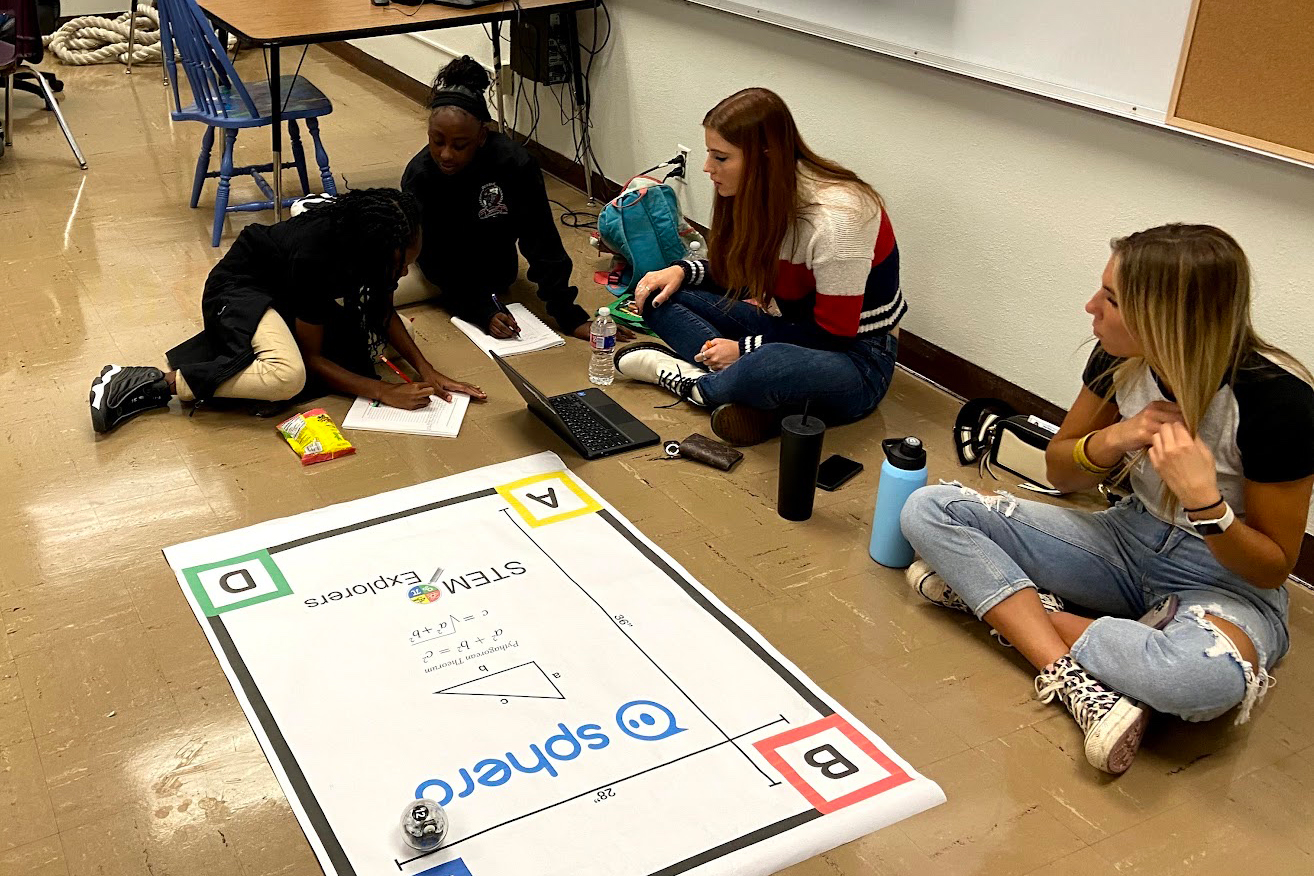

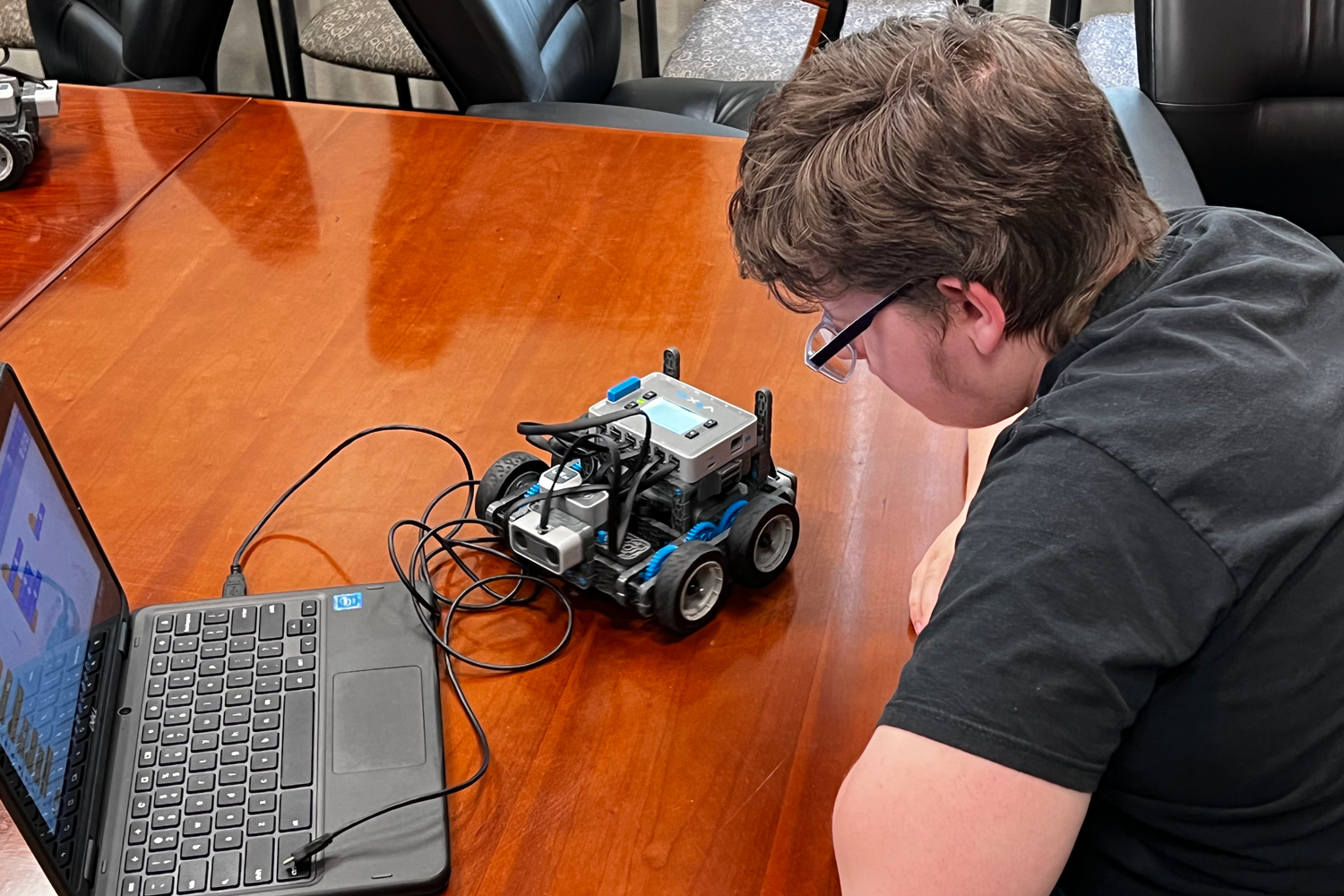

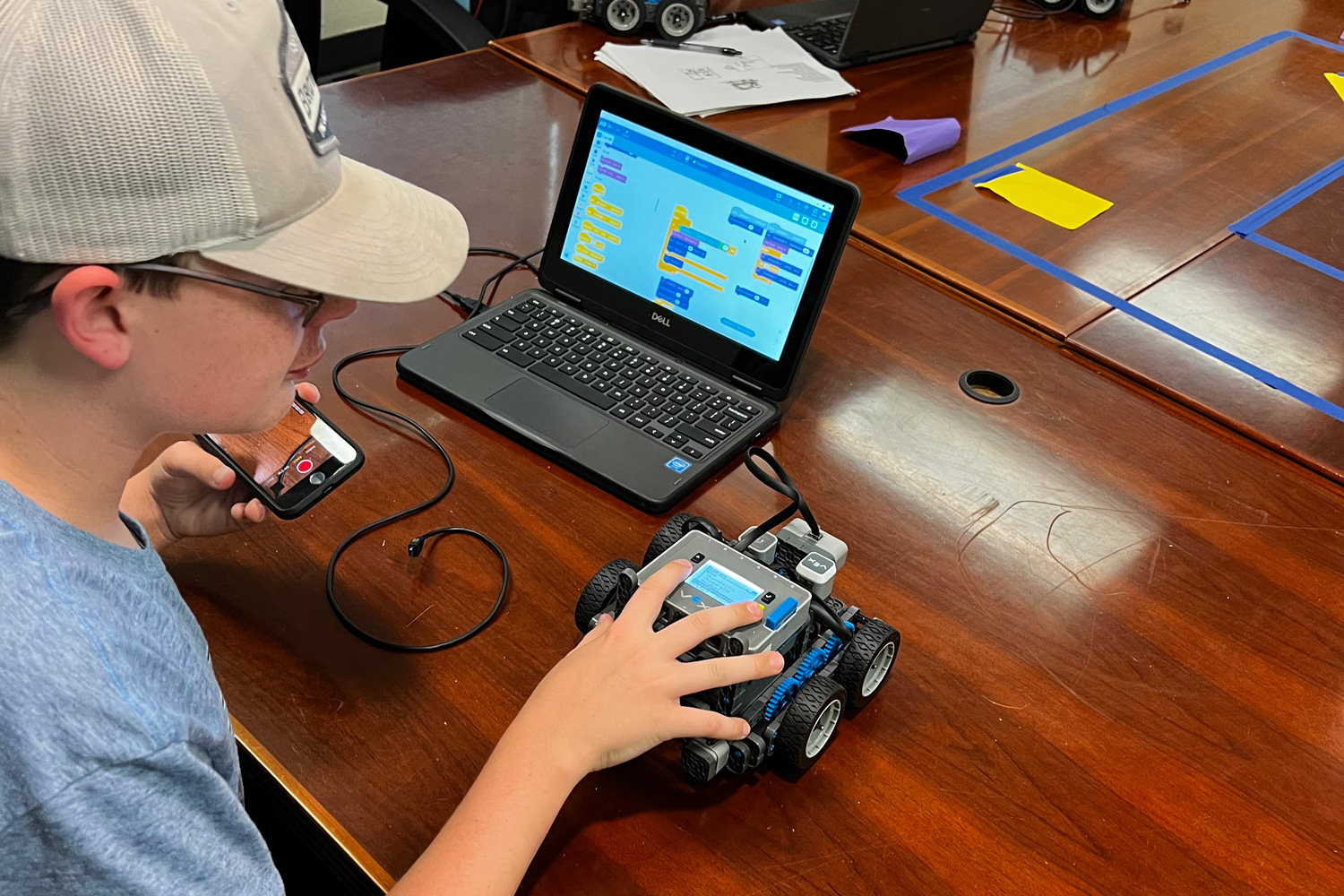

The STEM Explorers program provides free summer and day camps for foster care youth that include robotics, electronics, coding and programming, digital manufacturing, computer-aided design, and app development.

Since then, STEM Explorers has expanded to serve students with disabilities, behavioral difficulties, severe emotional disturbances and those involved in criminal justice – youth Kelly said would otherwise not get an invitation to join a robotics team.

“They're the kids that everybody hopes will leave at the end of the day,” Kelly said, adding that he sees himself in many of them.

When incarcerated and expelled students take part in the STEM Explorers, Kelly said it can reduce their dropout rates and recidivism. “My hope is that we're able to continue to provide robust educational experiences for these students who desperately need it,” he said. “We have scraped the money and volunteers together to allow students the ability to participate in these types of camps. In 2021, we had 80 kids and 86% of them had never been to any kind of camp.”

While Kelly and his team are not teaching the middle and high schoolers how to be scientists or engineers, they are providing something he said he missed in school – lighting potential career paths.

Some outlets he uses in these classes are robots as simple as a three-inch ball and others made from Legos. The students can learn how to program lights to flash or make motors operate.

Another activity offered is designing digital models for 3D printing.

“With STEM, it's hands-on and we can engage them in fun activities,” he said. “When we say, ‘Hey, we're going to work with robots,' then you get that instant engagement factor. The hope is that sparks all of their other skills and interests.”

As the students interact with robots, Kelly said they inadvertently learn problem-solving and cognitive behavioral techniques, such as discussing what “pushes their buttons.”

“We're just playing with robots and talking about our feelings,” Kelly said. “They get disarmed by that and it helps them bring their walls down a little bit and lower their emotions because they're focused on the play.

The challenges of providing this free program exhausted Kelly as he continuously sought out resources and support. But then he would see the responses of students who turn from reluctant to joyful participants.

Sometimes they sent him thank-you notes afterward. Another time, a group of incarcerated students programmed their robots to say “Dr. Kelly” over and over.

“They were engaged in it and having a good time,” Kelly said. “That really makes all the effort worth it because it's incredibly time consuming.”

It is time well spent, though. Last year, Kelly received a President's Excellence in Engaged Scholarship Award for Excellence in Community Engaged Teaching, which recognizes faculty whose long-term project or initiative demonstrates a significant and sustained commitment to addressing a community need or larger social issue through active collaboration with community partners.

And thanks to his NSF career grant, Kelly will be able to expand his STEM Explorers outreach under the umbrella of Incarcerated Students Prepared and Inspired to Re-enter their Education (INSPIRE).

“Dr. Kelly's research is a prime example of how education can make a positive impact on society,” said Jesse Perez Mendez, dean of the College of Education. “His work is not only innovative but also inclusive and equitable, promoting STEM education for underserved students. His personal journey is also inspiring and gives him unique insight into the challenges faced by young people who might feel abandoned.”

Training Future Teachers

Madelynne Greth, a third-year secondary education major with a concentration in mathematics, took a class with Kelly last spring. She began to work with students at the Lubbock County Juvenile Justice Center weekly as a service learning project.

“They're just kids who have made bad mistakes,” Greth said. “They are really appreciative of the program and it's fun going in there and talking to them. It's been a really eye-opening and good experience.”

As a student teacher at Roosevelt High School in Lubbock, Greth is already working with kids from different backgrounds. Kelly also hired her about a year ago to teach robotics with the STEM Explorers.

She combines both worlds as she transfers insight from the STEM Explorers program to the classroom.

“A lot of kids come from economically disadvantaged or bad homes and backgrounds,” she said. “So just being able to differentiate my instruction based off them and giving them that support in the classroom and outside of the classroom, I think it's very beneficial for them. It reflects in their grades.”

Kelly remembers how it felt for education to be catered to the mass population, but not the individual. Some teachers were great at outreach, while others were not.

“I think that's where the system needs work, is in identifying those students that need additional support and recognizing there are things going on beyond them being lazy students,” Kelly said. “Which I was, to be very clear. But there was more to the story that didn't come out until I was 15 that should have come out when I was 10.”

Kelly believes he can change this by training future teachers to have more empathy. He wants teachers to see their students as more than a sum of their behavior – rather, to take time and understand their behavior so the roots causes can be addressed.

Greth acknowledges the unique and fortunate situation she is in to learn from Kelly, who shares experience as both an educator and former foster youth.

“He gives me a lot of insight on what it's like because he can really relate to the students,” Greth said. “It shows the students that even though he was a foster kid who dropped out of high school, he still went on to college and got his Ph.D. So, it really is eye opening that they can still do something with their life and there is nothing hindering them from furthering their education.”

She will never forget watching students become interested in college for the first time within a few months of engaging with robotics. While college is not a viable option for every student, just discovering their potential opens them up to the possibility of other successful alternatives such as trade school and careers that do not require a college degree.

“Even if they don't want to go into a career with math, it shows them they can do something with their lives that they're interested in,” Greth said. “They're like, ‘Oh, I can do things I like I if I set my mind to it and try new things.'”

Spreading the Word

There is no doubt, the STEM Explorers program has made an impact. In 2021, Kelly was honored with the Inspiring Programs in STEM Award from Insight into Diversity magazine.

Despite the success, something was bothering Kelly. As he applied for grants to fund his camps, he kept being told there were already sufficient existing programs.

“There definitely aren't,” Kelly said. “There's a foster care system, but the system is focused almost exclusively on survival. It's making sure that the kids are alive the next day, quite literally, in some cases.”

To disperse education about foster care within academia in the U.S., he created the Journal of Foster Care, which publishes information from practitioners and researchers from all fields specifically related to foster care.

“There's a need for awareness,” he said. “There are very few of us that both drop out of school and then end up with doctorates. Then, there are even fewer of us that come out of foster care and survive that process. It's a small subset, but we exist.”

According to information released by the Texas Education Agency (TEA) last year, there are approximately 17,000 school-aged students in Texas schools who are in foster care.

“These students have significantly lower educational achievement than their peers not in foster care,” the TEA wrote.

Children from the ages of 14 to 17 made up 17% of children in the Texas child welfare system in 2019. The TEA revealed statewide, 1,212 young adults aged out of foster care that same year and lived, on average, in six different placements.

“Research shows that frequent school moves have a negative impact on academic achievement for students,” the TEA shared.

Within Texas in 2019, 25% of students in foster care dropped out of school, while less than 6% of their peers in the same graduation class cohort dropped out of school. Texas students in foster care have the highest dropout rate at 25% and the lowest graduation rate at 62.6%. Alongside this data, the TEA wrote: “This data demands attention and action.”

Kelly agrees.

“Right now, we're sending them out to the world completely unprepared,” he said. “If we can figure out how to get them more support, how to get them at least a high school diploma, then they can take those next steps.”

To Kelly, it all comes down to the treatment of foster youth. He believes all students deserve the encouragement he received during his trials that ultimately led to him earning a high school diploma, and then more than he could ever imagine.

“My hope is that we can build programs that are successful and work,” Kelly said. “I want to show the system that we can do it; that I can take a bunch of 18- and 19-year-old undergrads into a facility and we can work with the kids with this programming.

“I'm just a step for them. My hope is they don't remember me, but they remember something about what we did, and it sparks something somewhere down the road.”